An avid collector introduces a few of his friends.

One of the many important opportunities that college offers Dartmouth does it for our students and Harvard surely did it for me is that of being in the presence of writers. Most colleges invite many writers to give readings from their works, and these readings serve to create a special experience a sense of connection between students and authors. Also, they often lead students to buy the writers' books perhaps even, in an act at once of homage and of selfdefinition, to ask the authors to inscribe them.

During my undergraduate years, I had many opportunities to hear poets and novelists read. The occasion I remember most indelibly was a reading in 1955 by T.S. Eliot, who appeared on that occasion under the auspices of the Advocate, Harvard's literary magazine. I had competed unsuccessfully for membership on the Advocate, and I felt a special sense of yearning as I sat in Sanders Theater that evening, a desire to identify with this Harvard graduate whose poetry and criticism dominated the consciousness of most English majors. The author of "The Waste Land" and "Four Quartets," Eliot was perhaps the most significant living poet and critic in the intellectual lives of undergraduates.

Eliot said he wanted to preface his poetry-reading with a word of homage to Douglas Bush, an eminent Harvard Renaissance scholar. Eliot had written a number of essays downgrading Milton's status as an English poet; it was Donne and the metaphysical poets, he had argued, who were the major poets of England after Shakespeare. On that evening, however, Eliot announced that Professor Bush had pursuaded him that Milton must indeed be ranked among the greats. Here was T.S. Eliot confessing to a critical mistake. His confession was an epiphany. For a stunning moment it brought the audience into the intimacy of a writer secure enough, generous enough, to admit his judgment's vulnerability.

In later years, while I was at the University of lowa, I had many opportunities to meet writers who visited the Writers' Workshop: writers like John Hawkes, Czeslaw Milosz, Angus Wilson, Robert Coles, John Irving. In addition to meeting wellestablished authors, one of my greatest thrills was to meet young graduates of the Writers' Workshop whom the faculty regarded as having particular promise. There is a special joy in knowing writers during the formative years in which their work is developing and their experience is deepening. In nurturing the talent of these writers, colleges and universities perform an invaluable public service.

Of the scores of young writers whom I heard read, three stand out in my memory. The first is Deborah Digges, a poet whose work appears regularly in The New Yorker, and whose book Vesper Sparrows was published in 1986. The second is also a poet, Eric Pankey, whose first book, For the New Year, won the Walt Whitman Award of the Academy of American Poets in 1984, and whose second book of poems, Heartwood, is out now. The third is Allan Gurganus, author of the lively and distinctive novel, Oldest Living Confederate Widow Tells All, an extraordinary effort to recapitulate the meaning of the Civil War and the tragedy of the American South. I expect that each of these writers will make significant marks on the world of letters.

Of course, everyone comes to look upon certain books as special favorites. Sometimes they are special because of what they contribute to one's intellectual development or because of the circumstances or events associated with the time of one's first reading them. Sometimes they are special, too, because of their aesthetic impact as physical objects the quality of their binding or design or illustrations. But most often they are special because of the rareness of the truth in the intellectual and emotional chord that they strike.

There are any number of useful ways to characterize such special books. The American Scholar hit upon one. It invited a number of distinguished individuals to name books that have been undeservedly neglected by critics or the public. Several mentioned Henry Roth's Call it Sleep. The book was subsequently reissued in paperback and rediscovered by a new generation of readers.

Over the years I have compiled my own list of undeservedly neglected books. Many of these books are not likely to find their way onto a traditional Great Books list. Yet, they are important, revelatory, and transporting books. They spoke to me when I first read them, most as a young man, and I have no doubt that they would speak to students today in ways that are useful to their intellectual, moral, and emotional development. Below are a few of the many books that have been important in my life. I recommend them to you.

Calling the bookstore a "jealousmistress," President Freedman pursueshis passion for books.

This column regularly features the teaching and research interests of the professors at the College who shape the education of today's students. This month we turn to the man whose job it is to set the tone for all of Dartmouth: President of the College James O. Freedman, who spoke to the community last summer about his love for books. This "Syllabus" is adapted from that talk.

"It is difficult to explain why collecting books is so deeply satisfying," the president told a Spaulding Auditorium audience. "Many hooks are, to be sure, beautiful objects in and of themselves, and owning beautiful objects is undeniably satisfying. But there is more than that. Books can tell stories that possess a life of their own, and by possessing the book a collector may come near to feeling that he possesses that life."

Freedman divulged a secret with refreshing candor: that he was a atebloomer reader. With the story of his own first indulgence in books, he invited students to take up with the literary muse. "It was in July 1950, during the summer after my freshman year in high school," he told them. "My parents had quite properly required that I get a job that summer to earn money for college. I found a job washing dishes at the Elliot Hospital in Manchester, the New Hampshire city in which I grew up.

"Washing dishes was exhausting and boring. There was nothing to do during the long hours between meals. T dearly wanted to quit. Eventually I discussed my unhappiness with my father, who was a high school teacher of English. He was quite aware of the fact that I had yet to read a book on my own, outside of a class requirement not a single book. Sympathetic to my plaint, he allowed me to quit, but with the shrewd condition that I spend the rest of that summer doing some reading.

"And so I went with my father to a charming bookstore in Manchester, the Book Nook, and bought the volume that was to start my adult life as a reader and become the first book in my library: Sinclair Lewis's Arrowsmith. I soon read a good deal more of Lewis's work, then discovered W. Somerset Maugham. For as long as I continue to love books, it will ever be these two authors whom I recall most fondly, because they first excited my literary imagination and most blessed of all made me want to read more."

Karen Endicott

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryDartmouth's Steady Course

March 1990 By James Wright -

Feature

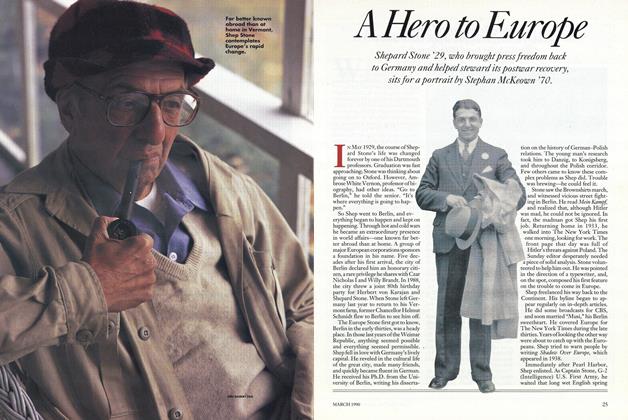

FeatureA Hero to Europe

March 1990 -

Feature

FeatureADDICTED TO CONVERSATION

March 1990 By Clayton G. Gates '90 -

Feature

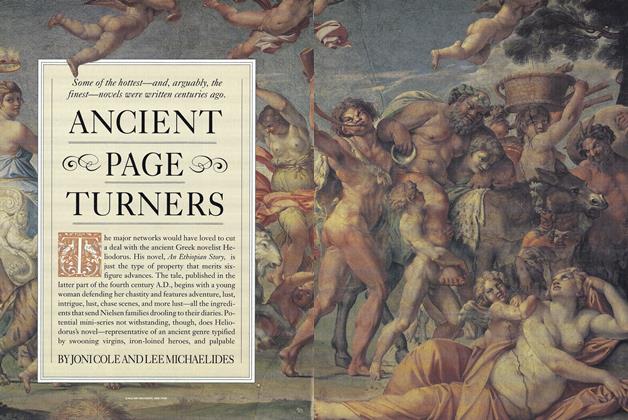

FeatureANCIENT PAGE TURNERS

March 1990 By JONI COLE AND LEE MICHAELIDES -

Feature

FeatureThe Purpose Gap

March 1990 -

Feature

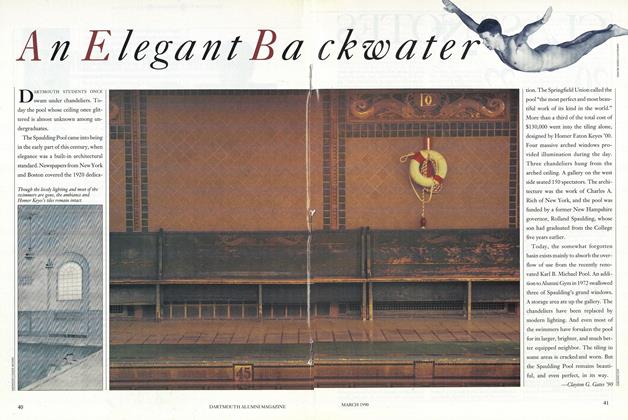

FeatureAn Elegant Backwater

March 1990 By Clayton G. Gates '90