Lobstermen, mill towns, and witchcraft shape New England still.

My course on the History of New England begins with a quiz. I ask students to list three items under various categories to complete the question: "When I think of New England I think of..." . Foliage, the seashore, mountains, and some mixture of white-steepled churches and village greens dominate the "visual symbols." The most frequently mentioned "historical characters" are Paul Revere, Daniel Webster, and either Sam or John Adams. Frost, Thoreau, and Hawthorne won four years in a row in the "literary figures" sweepstakes, as did lobsters, maple products, and clam chowder under "food." The fundamental results have been unchanged since I introduced the course in 1986. The student turning in the best quizthe one with the highest percentage of stereotypical answers—wins a chunk of maple sugar molded in the form of a lobster. Usually a midwesterner or auditing retiree wins the prize.

New England, however, has a much richer culture and tradition than these popular images suggest. Although not a single student has ever listed a factory or smokestack, the six-state region has always been the most industrialized section of the country. It has also been the most urbanized, ethnic, and Roman Catholic part of the United States—yet only "countryside" and WASPs appear in the quiz responses. Even the students of Irish, Italian, and French-Canadian descent and those who come from industrialized communities like Fall River and Framingham think foliage and Frost.

The primary goal in the course is to open students' eyes to what surrounds them here in the Northeast. President Emeritus John Sloan Dickey '29 used to speak frequently of a "sense of place." New England as a "place" is very much a product of the past. Its mountains, river systems, eccentric seacoast, and richly varied forests all stem from dramatic geological disruptions before human habitation. Three primary waves of settlement— first by Algonquian-speaking Indians, then by the English, and finally by Irish and continental Europeans—altered the landscape and brought continuous economic and social change to the region. Students are asked to make sense of well-known historical phenomena like Puritanism, the Salem witch trials, the leadership of Massachusetts in the era of the American Revolution, whaling, and the early development of publicly financed education. Less obvious topics include the origins of the New England town, its development over time, and the impact of localism and regional images in the popular press. There's very little on Daniel Webster or other national figures who happen to have been born in New England. I keep a tight focus on what took place within the regional borders.

of rural New England—Hanover is a prime example—stems from patterns of demographic change which affect lumbermen and plumbers who wouldn't be caught dead living in an A-frame or growing organic cabbage. Regional novels written in recent years rely heavily on the traditions of witchcraft, the town as a social microcosm, and the contrast in lifestyles between natives and newcomers.

A final set of observations. One bonus from offering the course has been the way it educates me. All students have to write a lengthy research paper on a narrow subject. The gems that appear often make their way into next year's lectures. Dartmouth students have taught me about harvesting cranberries John Kennedy's grandfather, the construction of the Hoosac Tunnel, water levels in the Rangeley Lakes, the Rhode Island-Connecticut boundary, and much more. The much more includes lots on Dartmouth. One paper—on the history of skiing at the College—appeared in Gnosis, the student literary publication.

The following books are either assigned for the History of New England course or are being considered for assignment. All but the Wilson volume are in paperback.

J ere Daniell's concise summation for why he studies New England conjures another Yankee stereotype: practicality. Says the professor dryly, in his north-country accent,"lf you're going to be around a place, you may as well understand it. Had I ended up teaching in Arizona, I'd probably be working on Arizona history."

Danicll has the right credentials to teach about the region. He was born into an old New England family, raised in the small mill town of Millinocket, Maine, and educated at Exeter, Dartmouth, and Harvard. At Dartmouth he was a member of Alpha Theta fraternity, manager of the basketball team, Phi Beta Kappa, Casque & Gauntlet, winner of the Colby Political Science Prize, and valedictory speaker for the class of 1955. Daniell says he always knew he wanted to teach, but he changed his mind a few times before choosing his subject. Expecting to become an engineer, Daniell enrolled at Dartmouth like his father (Warren '22) and two older brothers (Warren Jr. '48 and Samuel '51). Once exposed to the range of curriculum options, Daniell drifted from pre-engineering to philosophy to the government department, where he found a mentor and thesis advisor in Professor Arthur Wilson. (Ironically, Daniell never took an American history class as an undergraduate.) After earning his adv anced degrees at Harvard, he returned to Dartmouth as a faculty member in 1964.

Daniell chose the topics for his first two books {Experiment in Republicanism: New Hampshire Politics and the American Revolution, Harvard University Press, 1970, and Colonial New Hampshire: A History, KTO Press, 1981) because scholarship in those areas needed further exploration. "I like to poke around the edges to find unchartered turf. The last thing I'd ever do is write about Thomas Jefferson or George Washington, " he says.

Daniell's current project—a hook about New England towns (he asserts that there are exactly 1,401 of them)— takes him outside the Granite State. When the work is completed in the middle of this decade, it will include essays on everything from town foundings to their governance to their use as artistic images in fiction—in short, "any subject having to do with these communities is fair game," explains the professor.

Students in Jere Daniell's class learnthat steeples and greens are only twoaspects of New England.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

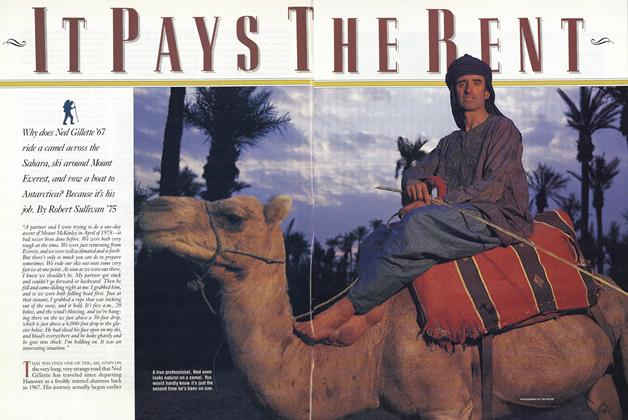

Cover StoryIt Pays The Rent

April 1990 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

FeatureTaking God's Word For It

April 1990 By Karen Endicott -

Article

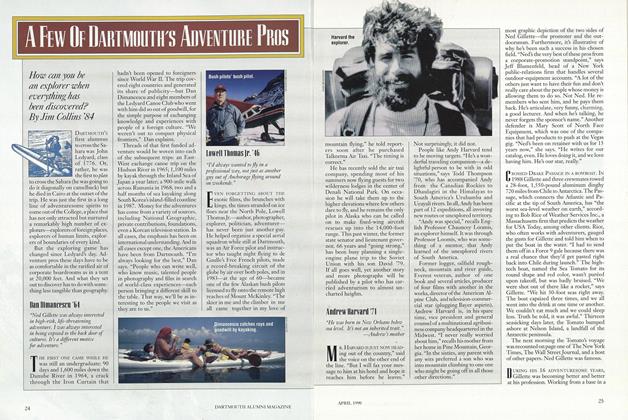

ArticleA Few Of Dartmouth's Adventure Pros

April 1990 By Jim Collins '84, Andrew 's mother, Ed -

Article

ArticleOn chemistry, Cuba, and other radical elments on the campus.

April 1990 -

Article

ArticleThe Satanic Verses: Why Were Muslims So Offended?

April 1990 By A. Kevin Reinhart -

Class Notes

Class Notes1983

April 1990 By Kenneth M. Johnson