• While researching our story on religious fundamentalism, we got to wondering why Muslims worldwide reacted so vehemently to the publication of Salman Rushie's novel, TheSatanic Verses. Fundamentalists such as the Ayatollah Khomeini were not the only ones infuriated. What was it that united Muslims against a mere book?

We asked Dartmouth Assistant Religion Profession A. Kevin Reinhart to give us an explanation. During the height of the Rushdie controversy he was doing research in Yemen and Syria. He wrote us in January from Istanbul, Turkey, where he has been researching Islamic law on a Fulbright grant.

It is as impossible to say what Muslims as a whole thought of TheSatanic Verses as it would be to say what Christians or Jews thought of "The Last Temptation of Christ." (That the Rabbinate in Israel banned the film, doesn't tell us what Jews in France thought of it.) Nonetheless, the large majority of Muslims I've talked to in the Middle East on this last visit, in the United States, and at Dartmouth, were offended by Rushdie's fantasy of early Islamic histoiy. Those offended included traditional Muslims in the little Yemeni town of Tuba, Muslim activists in Sanaa, leftist Muslims in Damascas, liberal Muslims in Turkey, and all sorts of Muslims in Boston, New York, and Hanover. While few supported Iran's capital sentence passed on Rushdie (including Saudi Arabian and Egyptian legists—Khomeimi's was a rather odd reading of Islamic law), the sense of offense was real, and, I believe, understandable.

As many Muslims see it, the very identity of the Muslim community is predicated on the divinity of the Koran; it is the record of God's speech transmitted through the Prophet Muhammad. In this respect Muhammad was a kind of distortion-less loud- speaker for the Divine Word. He was an inerrant human protected from moral failure and therefore an inerrant transmitter. In addition, his nobility of character, gentility, and unflagging devotion to the Message he bore (despite bloody opposition) made him both a perfect vehicle for the Message and its perfect embodiment. Hence not only Muhammad but his family and Companions were part of the best of generations, and formed a community transformed by virtue into a force that quite literally spread to every sector of the globe.

A part of The Satanic Verses retells the formative story of Islam. Here, Rushdie depicts a fuzzy businessman, Mahound—called by the scurrilous medieval corruption of his name (which is also in English a synonym for the Devil). He's a confused and rather bumbling fellow, unable to distinguish the promptings of Satan from the promptings of God—a god who may in fact really be a piapic Hindu cinema idol. It doesn't help that, along the way, the workers in a brothel are given the names of the Prophet's wives, thereby insulting Muhammad's family while also resurrecting the medieval European slander of the Prophet as a lecher. In The Satanic Verses this dismal fellow fashions his ravings and delusions into what is clearly intended to be the Koran.

Rushdie's fiction attacks the reliability of Islam's transmitter, his character, and the character of his heroic Companions and family; in the process he reduces the Book to a mere by-product of its source—a fallible, dim, desert trader. That the assault follows so closely medieval (and later) Christian polemic is a bitter gratuity added to a poisonous insult. At a stroke the emotional sensibilities of Muslims are assaulted and the theological legitimacy of Islam itself is sapped.

No small part of the offense comes from the nature of the sourceRushdie himself is a nominal Muslim who has "turned Tory." A Yemeni told me, "It would be different if he were Christian; we expect that sort of thing from them." There does seem to be a class of third-world wog-basher, selfhaters, we might say, whose cachet comes less from the originality of their insights than from the fact that as thirdworlders they are saying the nasty sort of stuff about "them" that it is no longer fashionable for "us" to say. A question worth asking is: would the pronouncements of Rushie, or of, say, V.S. Naipaul, on third-world matters be read and reviewed as seriously if their names were Russell or Norton? The Satanic Verses is surely a parricide of a sort—the work of an angry Anglicized ethnic Muslim irritated by what in all his works he has depicted as an obscurantist theology wielded by hypocrites conniving at the ignorance and bigotry of their followers. In this glittering novel he slays what alienates him from the English and what repels him at "home."

Very well, then, the American reader of the newspaper might say, granted that The Satanic Verses is offensive both because of what it says and who says it—still the question remains, why all this despicable book-burning and banning? A Peace Corps woman in Sanaa, shattered by a discussion in her English class of the Rushdie affair, wondered, "What's the big deal? They don't have to read it, or even buy it." She was right, of course, but she missed the point.

This Peace Corps woman assumed, as most of us here do, that society is an instrument for the promotion of "life, liberty, and the pursuit of [individual] happiness." A book, especially, is as-sumed to be a kind of independent act by an author; reading it is a transaction voluntarily entered into (unless read perforce in an English lit class), and the autonomy of the writer and of the reader is now taken for granted. Morever, from the Romantic period on, we've had the sneaking suspicion that a work of art isn't true, isn't significant unless it opposes, unless it is avant garde, unless it offends.

Yet for those who would ban TheSatanic Verses, society is not a collection of monads facilitating each other's "happiness," but rather a collective instrument to facilitate the individual's moral development. Art can't always be constructive, but it ought not to be destructive, they believe, or reckless of the truth which society seeks to embody and live. When the case of "The Last Temptation of Christ" was brought up, the Yemenis I talked to were astounded. "And it wasn't banned? But why does freedom of speech include the right to insult a prophet [as Jesus is considered by Muslims]?" one demanded. Particularly, blasphemy offends not merely because it is blasphemous but because it endangers others—it is shouting "fire" in the theater of public life. No bromides about the sorority of humankind, or the unity of all religions, can conceal the chasm between these two competing views of the nature of civic virtue.

I should close with a review of Rushdie's book. The Satanic Verses does not achieve all it aspires to, but is by turns touching, acrobatic, and comic, and it is always engaging. I liked the book very much; the more one knows about its subject, the more it seems something close to a masterwork. And, I think, it is offensive.

Rushdie didn't just anger the right wing.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

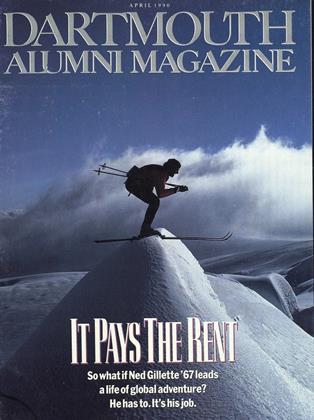

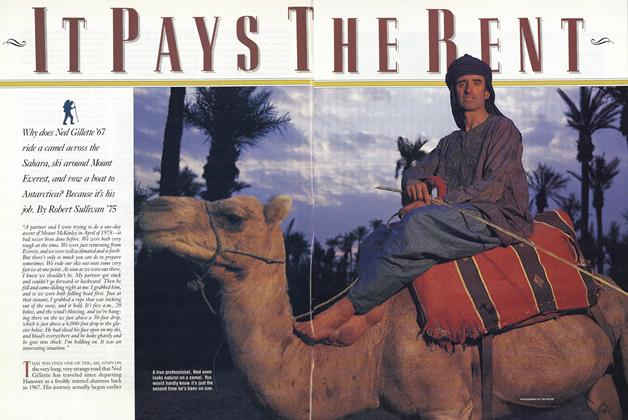

Cover StoryIt Pays The Rent

April 1990 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

FeatureTaking God's Word For It

April 1990 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleA Few Of Dartmouth's Adventure Pros

April 1990 By Jim Collins '84, Andrew 's mother, Ed -

Article

ArticleOn chemistry, Cuba, and other radical elments on the campus.

April 1990 -

Article

ArticleA SENSE OF PLACE

April 1990 By Professor Jere Daniell '55, Joni B. Cole -

Class Notes

Class Notes1983

April 1990 By Kenneth M. Johnson