Why does Ned Gillette'67ride a camel across theSahara, around MountEverest, row a boat toAntarctica? Because it's hisjob.

"A partner and I were trying to do a one-dayascent of 'Mount McKinley in April 0f 1978—ithad never been done before. We were both verytough at the time. We were just returning fromEverest, and we were well acclimated and so forth.But there's only so much you can do to preparesometimes. We rode our skis out onto some veryfast ice at one point. As soon as we were out there,I knew we shouldn't be. My part?ier got stuckand couldn't go forward or backward. Then hefell and came sliding right at me. I grabbed him,and so we were both falling head first. Just atthat instant, I grabbed a rope that was stickingout of the snow, and it held. It's five a.m., 20below, and the wind's blowing, and we're hanging there on the ice just above a 30-foot drop,which is just above a 6,000-foot drop to the glacier below. He had sliced his face open on my ski,and blood's everywhere and he looks ghastly andhe goes into shock. I'm holding on. It was aninteresting situation."

THAT WAS ONLY ONE OF THE, AH, STOPS ON the very long, very strange road that Ned Gillette has traveled since departing Hanover as a freshly minted alumnus back in 1967. His journey actually began earlier but still locally, at a rope tow on a Currier-and-Ives hillside in Vermont in 1948. "I was three," he says. "I was new and so was the sport. I was small and the mountains were big."

Now, in the world of adventuring, Gillette is big and the mountains are much, much bigger.

Since those afternoons as a precocious downhiller in Vermont, Gillette has, in more or less chronological order, survived a harrowing stint as a prototypical New England preppie (shiver); moved on to Dartmouth where his twin loves were Theta Delt fraternity and the cross-country ski team; competed as a member of the U.S. Olympic team; moved on to business school (shiver, shiver); become a hippie living in a one-room flat (ahhhh); enjoyed a career as a top-flight ski instructor; authored a couple of books, one of which, Cross-country Skiing, is in its third edition; and started a cottage industry in adventuring. This last pursuit, which has represented a seminal shift of gears in Gillette's life—it has made him a nameinvolves putting together expeditions and pitching them to corporations that might want to contribute money and thereby align themselves (and their products) with Gillette's attractive, exciting, pine-scented ideal.

Against mountainous odds, Gillette's idea has clicked, and since becoming an adventuring pro—a star in a profession that has its share of Dartmouth grads (see the accompanying sidebar on page 24)—Gillette has skied on all seven continents, sailed the roughest seas, and climbed many of the highest peaks. Next up—at least among the "major" expeditions—is a six-month camel caravan across the Sahara desert, to be undertaken in 1991. Since, as Gillette readily admits, "promotion is half of what I do," Gillette recently ventured to Africa. His mission wasn't to test the sand but to drum up support for the projected 12-person eXtravaganza.

Africa is where we caught up with Ned Gillette, which is obviously a hard thing to do. During five days in Morocco we began to get the barest sense of what a distinctly odd but exciting life the noted outdoorsman leads.

IN MOROCCO GILLETTE IS TRAVELING WITH Susie Patterson, a former U.S. Olympic skier. Patterson comes from an outdoorsy family—one of her brothers, Ruff, is Dartmouth's new ski coach. Therefore she had been aware of Gillette and his exploits Before they started dating two years ago. "Oh, sure, I'd heard of Ned," she says, ever smiling. "I did have an idea of what I was getting into. I did not know some of it would be quite so extreme, but I knew some of it like rowboats across the ocean, for instance, or camels across the Sahara—might seem a little crazy."

Last year Gillette relocated from Stowe, Vermont, to Sun Valley, Idaho, to be with Patterson. In the vagabond world of Ned Gillette, such a move represents a major commitment. He admits that, as he is constantly mobile and ever-imperiled, he has to "keep emotional overhead low." At 44 he is a veteran of nearly as many failed relationships as of mountain summits. "There's an obvious down side to what I do," he says. "But in another way, I've found I'm well suited for the life I've chosen. I'm not a mature person by nature. Having kids and a house just weren't things I was very interested in. Susie feels much the same way, and we're doing great. We have an awful lot of fun together, and she loves to go on all these things. That makes it all the better."

Susie likes to go on most of these things. Morocco she wasn't so sure about. The fudge factor was that the caravan would not necessarily be a Ned Gillette Enterprise. Gillette had been recruited to co-direct the trek by Michael Kirtley, a Kentuckian who is president of something called The America to Africa Society. Gillette, figuring this to be one of the very few ways to hitch a camel ride across the Sahara, readily agreed. But the A-to-A, it was becoming increasingly evident in Morocco, represents Kirtley's highfalutin' effort to bring our country and their continent closer together—it's one of those sister-cities deals. The caravan, Kirdey's showpiece, seemed to have none of the offbeat, goofy charm that is the hallmark of Gillette's usual expeditions. "I don't know about this one," Susie says as she rides the Marrakech Express which is, as the song says, taking us to Marrakech. "A lot of adventures have that Save-the-Whales or Peace-on-Earth stuff attached to their adventures. It helps raise money and so forth. But Ned's never done that. His things have always been just sort of for the fun and adventure of it. This one—it doesn't seem like Pure Ned.

That had become apparent right off the bat in Rabat, where all manner of Moroccan royalty had feted the camel crew with lavish parties, dinners, and tours of the an tiquitous city. Gillette was smooth and po Lite throughout, but even he was wondering at the enormity and fervor of Morocco's welcome. Apparently Kirtley had convinced the monarchy that this caravan—co-directed by the famous American adventurer Ned Gillette and the equally famous African sa fari leader Mano Dayak—would do as much for Moroccan tourism as any old Malcolm Forbes shindig in Tangiers. So the crown had put up a quarter-million dollars for the publicity junket, and was putting on the Ritz for Kirtley, Gillette, Patterson, Dayak, and company. This "company" included a few journalists, a few freelance photographers, and a few Kirtley family members. "Kinda weird, eh?" says Gillette as the train rolls south from Casablanca. "All that jazz in Rabat, with Michael signing the holy book and all. It's different than what I normally do. I mean, I promote a lot, I admit that. But this is something else. It's not what I normally do, I promise."

Gillette proceeds to talk about that: the slightly more normal things that he normallydoes. It all started, he figures, back on that Vermont hillside when he was three.

"No," he says. "I take that back. I think it all started...The stuff you want to talk about—that all started one afternoon when I was a preppie at Holderness. Before Holderness, I didn't have a lot of confidence and I didn't really excel at any one sport. So to make the varsity ski team I took up crosscountry, 'cause all the best skiers were racing downhill. I had these ratty old red skis, and over Christmas I went around and around our garden in the backyard—double sessions, morning and evening. The January time-trial remains my proudest moment in skiing—it was a boyhood dream come true. I was coming toward the finish and the guy in front of me fell and I won. It was just great! I've never given up since. My whole life since then has been a life of getting things done. But just barely getting things done. I barely won that time-trial, barely made the Olympic team, succeeded on McKinley after failing once. The thing is, though, ever since that afternoon at Holderness, I have gotten things done."

Seeming to digress, Gillette suddenly confesses that he has never been the strongest, fittest, or most talented outdoorsman on any of his adventures. "I know I'm not the best climber, skier, or ocean-goer around, but I have a good imagination. And I'm good at the artistic side of these expeditions—the writing and photography. I'm good at putting it all together. I get the best experts to go along with me because they know I'll get it done. I've always figured that this all dates to an afternoon at the Holderness School."

Newly confident, Gillette arrived in Hanover when the campus was experiencing the Bobby Vee/Brenda Lee calm of the early sixties. "Anti-war movement?" he asks, smiling broadly. "Not hardly. In fact, I was in the ROTC back then. None of that turmoil had hit yet." Gillette was a middling student at best, as he much preferred the basement of Thumpty Dump and the glades of the golf course to Baker's stacks. "I used to have a few brews, and I used to ski all the time. That's what I remember best about Dartmouth." A Nordic disciple now, he captained the cross-country team. Upon graduation, he entered the national team's development program, and by '68 he was part of the international traveling squad. His first race in Europe was the storied Holmenkollen in Oslo, and he promptly went right on his butt in mid stride before a throng of 50,000 Norwegians. He performed little better at the Grenoble Olympics. And that about brings down the curtain on the big-time ski-racing career of Ned Gillette.

Next came what Gillette, in an Outside magazine cover story, once called his "brief flirtation with being a serious person." He lasted for two years in the executive training program of a paper company, and precisely one day at the University of Colorado's business school. His fling with neckties was foredoomed when, in 1972, he signed up for a month-long ski trek. Something out there, out in the wilderness, bit him. Will Steger, another pro adventurer who has become famous to the point of TV for his 4,000-mile dogsled traverse of Antarctica, says, "Ned's very much like me. He has to go out there. And now he has to keep going back."

Starting with that first 1972 trek, during which the less airy Gillette might or might not have "found himself out there," Gillette has:

SKIED ALASKA'S BROOKS RANGE. GILLETTE and three others traveled 600 miles in 30 days across the northernmost mountain range in the world. They wore wooden skis and cable bindings. "This was my first long trip," Gillette has written. "The first day, busting trail through knee-deep depth hoar under 70-pound packs and the minus-35- degree evening quickly eroded my romantic notions of expeditions. But I learned to remember only the good times: like a hot cup of tea in cold hands, shared camaraderie, and especially the airdrop of warm chocolate-chip cookies from a friend's Cessna."

SKIED THE HIGHEST ARCTIC. IN 1977, Gillette and three others went as far north as land allows, Ellsmere Island at the top of Canada. In 52 days they skied 450 miles, lugging all their food and gear on eight-foot sleds.

CIRCUMNAVIGATED" ALASKA'S MOUNT MC- Kinley. Five interconnected glaciers form a 90-mile ring around the summit of North America's highest peak, which tops out at 20,320 feet. In 1978 Gillette and three others used crampons, ice axes, and skis to make the circle.

Gillette, ever a pro, has a marketer's mindset and is always coming up with catchy ideas like bringing ashore the nautical term "circumnavigate" to describe a landlocked orbit. He has practiced a form of international trespassing that he cutely calls "guerilla skiing," and we'll get to that later. It's all part of his game: he's in a business that loves a hook, that demands firsts. He must be the first to do this, or the first to do that, in order to attract sponsorship. "And, let's face it, everything's been done," Gillette admits genially. "Everest has been climbed, the seas have been sailed. But they haven't been done all these different ways. The angles I come up with seem bizarre and risky. That's what entices people." Therefore he doesn't merely climb McKinley, he circumnavigates it. He doesn't merely ski Tibet, he guerilla skis it.

ASCENDED MCKINLEY IN A SINGLE DAY. Again in '78, Gillette and a partner who has accompanied him on some of his greatest triumphs, Galen Rowell, twice shot for the summit. The first effort culminated in the crisis that is described at the top of this story. To pick up from there: Gillette eventually carved a boothole in the snow, and the two recovered their senses and eventually made it back to camp. After Rowell's face healed, they tried again. "This time we both began getting altitude sickness at 17,000 feet. At 19,000 feet Galen would collapse, and I'd revive him, then I'd collapse and Galen would revive me. We kept falling down, over and over. But we made it. The top felt wonderful, and weird." The round trip took 19 hours.

TREKKED ACROSS THE KARAKORAM HlMAlayas in Pakistan. In 1980 Gillette and three others covered 285 miles in six winter weeks. "This was the most grueling of all the expeditions," Gillette has written. "To be self-sufficient we each lugged 120 pounds. At one point we climbed on nordic skis to 22,500 feet to traverse the south face of Skia Kangri. Temperatures sometimes swung 100 degrees from day to night. When we finished at Hunza, we'd each lost 25 pounds."

BEEN AMONG THE FIRST AMERICANS IN 48 years to climb in China. In 'BO Gillette, Rowell, and Jan Reynolds summitted on and skied off—Muztagh Ata, which is 24,757 feet high. (Reynolds set the women's highaltitude skiing record on the trek.) On the last day the trio climbed nearly 5,000 feet from their high camp. Gillette describes the descent alternately as "the ultimate prize" and "the one truly great run on the perfect big skiing mountain." As they cruised through the powder, they looked out over Russia at the setting sun.

CIRCUMNAVIGATED EVEREST. IN COMPLETING their grandest circuit, Reynolds and Gillette started and finished at the summit of 23,442-foot-high Pumori. They thrice ascended to 20,000-foot-high mountain passes. Nevertheless the adventure drew criticism from the outdoor community. Gillette had to leave the expedition midway to fulfill sponsorship commitments at a skiequipment: convention in—of all placesLas Vegas. Then he flew back to Everest and resumed the effort. It was, perhaps,

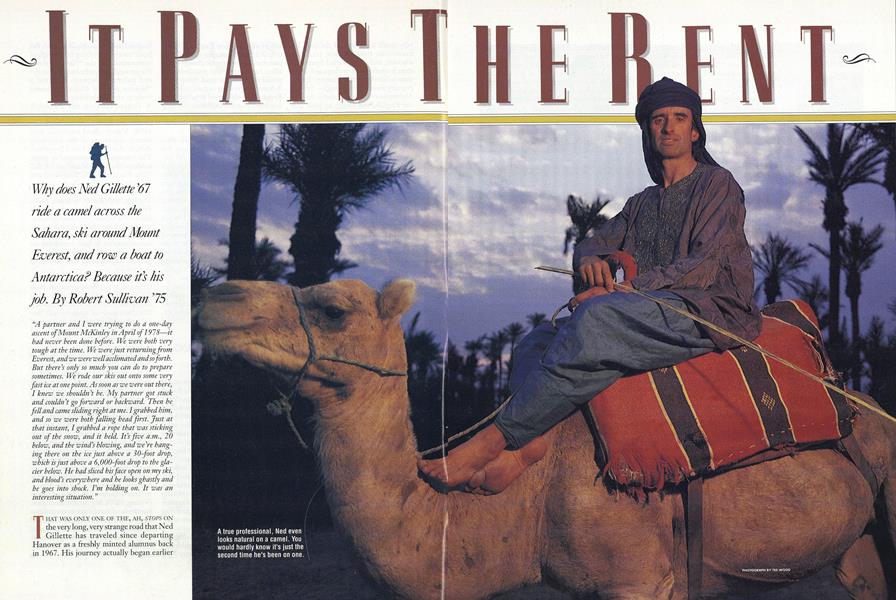

A true professional, Ned evenlooks natural on a camel. Youwould hardly know it's just thesecond time he's been on one.

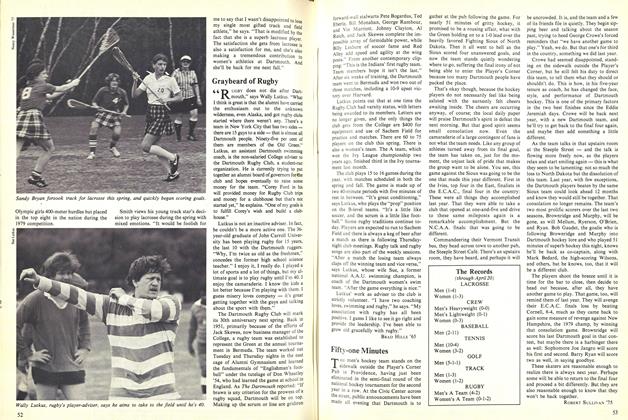

A middling student atbest, Gillette captainedthe crosscountry team.at Dartmouth.

Outside a Moroccantheme park, Ned does aphoto op with girlfriendSusie Pa tterson andco-leader Mano Dayak.

Whether scaling ice walls inNepal or hauling sleds across theArctic's Ellsmere Island, Ned hasnever been the strongest, fittest, ormost talented member of thegroup. Instead, "I have a goodimagination," he says. "T'm goodat putting it all together."

Base camp at Mount Pumori,the start and finish of what the mastermarketer called his"circumnavigation" of Everest.

In 1988, Gillette andthree seasick crewmatesrowed the Sea Tomatoto the Antarctic.

Climbing above 20,000 feet in a winter trek across Pakistan's Karakoram Himalayas, he suffered 100-degree swings in temperature and lost 25 pounds in six weeks.

"NativeMoroccans,traditionallygarbed, arebanging dru msand chantingloudly in honor ofthe daringWesterners whowill ride thecamels. The funnything is, as Gilletteadmits in the hotellobby, 'I've neverbeen on a camel.Not yet.'''

"If the sun issetting just sobehind a dune,and if Gillette looksproperly majesticatop a camel, thenthe money shouldstart to flow."

"It's all part of hisgame: he's ina business thatdemands firsts.He must be thefirst to do this, orthe first to do that,in order to attractsponsorship .''

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTaking God's Word For It

April 1990 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleA Few Of Dartmouth's Adventure Pros

April 1990 By Jim Collins '84, Andrew 's mother, Ed -

Article

ArticleOn chemistry, Cuba, and other radical elments on the campus.

April 1990 -

Article

ArticleThe Satanic Verses: Why Were Muslims So Offended?

April 1990 By A. Kevin Reinhart -

Article

ArticleA SENSE OF PLACE

April 1990 By Professor Jere Daniell '55, Joni B. Cole -

Class Notes

Class Notes1983

April 1990 By Kenneth M. Johnson

Robert Sullivan '75

-

Sports

SportsFifty-one Minutes

May 1980 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Article

ArticleFootball From Down Under

December 1992 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Article

ArticlePosthu-Mously, Norman Maclean Takes On a New Element

February 1993 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryNO HOLDS BARD

MARCH 1994 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

FeaturePeter Smith's Tribal Links

Novembr 1995 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Cover Story

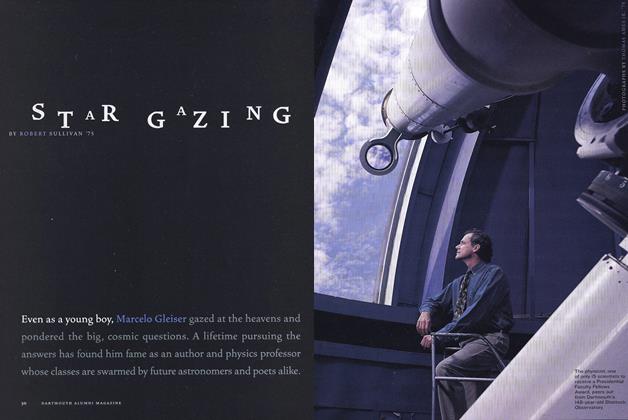

Cover StoryStar Gazing

July/Aug 2003 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75