Scholars take a termlong look at religiousfundamentalism.

FROM BLUE-HAZED TELEVISION rooms in middle America to mosques in the Middle East to lush rice paddies in Indonesia, religious purists are taking a stand against the secularism of the modern world. As they bow to age-old traditions and to the teachings of preachers, they bow out of such modern notions as the total separation of religion and government and the secularist view that religion is but one realm of life. They fight these ideas with weapons as sublime as they are powerful: loyalty to ideals, allegiance to authority figures, prayer, morality, unswerving devotion to God—the very qualities and concepts that many, if not most, people regard as virtues. Yet, as religious leaders from the late Ayatollah Khomeini to the televangelist Jerry Falwell are well aware, these graces have the potential to uplift more than the lives of devout individuals. If properly harnessed, these graces have the power to move social and political mountains.

For years academics ignored these movements because they seemed to be on the fringe of religion and society. The religious right's growing political clout prompted scholars to give the groups a closer look. "The conservative reassertion of religion is a phenomenon to be studied with detachment," says Religion Professor Charles Stinson, a specialist on Christianity. "We need to understand its genesis, its appeal, and its possible valid points. The subtext is that it is a problem when it decides to interfere with what others believe."

The term "fundamentalist" first referred to early twentieth-century American Christian evangelists who sought to counter liberalism within the church. Among other things, they took stands against Darwinism and rejected anything but traditional, literal interpretations of the Bible. In the late 70s journalists reporting on the Iranian revolution applied the fundamentalist label to the followers of the Ayatollah Khomeini who wanted to establish a fully Islamic government and way of life. In linguistically linking Christian fundamentalists and Iranian revolutionaries, the press forged a popular definition of fundamentalists as any group that seeks to live by strictly religious formulations without secular compromise.

Scholars at Dartmouth have taken a lead in questioning this blanket definition of fundamentalism and analyzing whether fundamentalism should be considered a single sociopolitical and religious phenomenon. Over the past three years, three professors—government's lan Lustick, history's Gene Garthwaite, and religion's Charles Stinson—have co-taught a sophomore summer course on comparative reli gious fundamentalism. From an initial enrollment of 33 the course has swollen to 100 students, testimony to rising popular interest.

Last spring religious fundamentalism received even more attention at Dartmouth when it became the inaugural theme of the College's first Humanities Institute, a groundbreaking term-long faculty research forum. The program is the brainchild of professors in Dartmouth's humanities division. Rather than requesting a unifying central building like the social sciences' Rockefeller Center, they opted for a yearly think-tank. Funded with seed money from the Mellon Foundation and the National Endowment for the Humanities, this year's institute, on gender and war, is already underway, and the next two-one on medieval manuscripts and the following on the discovery of America, are in the works. Operating during spring term, the institute provides a forum for scholars from various departments at the College and visiting researchers from other universities to join together in studying a single topic. Released from one course of their teaching commitments for the term, professors have the freedom to delve into their research alongside their colleagues. Twice-weekly seminars open only to institute participants serve as a focus for the group, but collegial discussions flow throughout the term, spilling over into dinners, weekend get-togethers, and walks around campus.

Last spring's institute on fundamentalism—cochaired by Religion Professors Robert Oden and Kevin Reinhart—attracted 12 Dartmouth professors from various disciplines, including anthropology, government, history, music, and philosophy. The institute also brought four visiting fellows to campus for the term: Duke University's Director of Religious Studies Bruce Lawrence, who has written extensively on comparative fundamentalism; Bonnie Morris, a historian and research fellow at SUNY Binghampton who studies Lubovicher Jews; Martin Riesebrodt, a sociologist from the University of Munich who specializes in radical religious reform movements in the United States and Iran; and June Santosa, an Indonesian who is a doctoral candidate at Boston University who is researching the psychology of religion.

The institute's academic leader, brought in as the prestigious William H. Morton Humanities Fellow, was Albert Hourani, a former Oxford University reader in Middle East studies who is widely regarded as the foremost western scholar of modern Middle Eastern histoiy. Says Oden, "He is in a sense the 'father' of a whole generation of Middle Eastern specialists, to such an extent that it often seems difficult to think of any major scholars who have not been students of Albert Hourani in some direct or indirect sense for a part of their lives." Hourani, for his part, says that the institute provided him with the oppor tunity to "read widely and think of new subjects." He also guided discussions and dissected arguments at the institute's seminars. When Albert Hourani talked, even the most seasoned professors listened. "He's better than his reputation," claims Visiting Fellow Bruce Lawrence, "and his reputation is the best in the business."

Participants say people like Hourani bring new life to an isolated college where most academic departments are too small to include many professors with overlapping specializations. "It feels like the voltage has been turned up around here," Kevin Reinhart said last spring. In a sense the Humanities Institute is a substitute for the kind of intellectual stimulation that graduate students doing original research regularly provide for professors at large universities. In some respects the institute is even better. Participation is like being on sabbatical without leaving campus, according to former Dean of the Humanities Richard Sheldon, who oversaw the institute's creation. "Professors are allowed to recharge, read, and work. They become better teachers when they return."

It might come as a surprise that by the end of the term such a highly acclaimed thinker as Hourani admitted that he was still not sure what fundamentalism means, except to call it "a protest against new ideas even in religion and a reaction and protest against modernity." Hourani's perspective echoes the many attempts by institute scholars to define the term and test it out by examining a variety of religious groups—including Islamic movements in Turkey, Iran, and Indonesia; American Protestants and Roman Catholics; and Israeli and American Jews. While the group did not forge a single definition of fundamentalism or compile an exhaustive list of fundamentalist groups, says Dartmouth's Kevin Reinhart, "the process of defining a phenomenon makes you examine data in new ways."

Several characteristics of fundamentalist movements emerged repeatedly. Next time you think about fundamentalists, try out the applicability of these features that institute guest lecturer Grant Wacker, of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, outlined to describe Protestant fun-amentalists in the United States. (To get you started, how about the Puritans, or Eleazar Wheelock? Were they fundamentalists?)

• Fundamentalists, says Wacker, tend to be "ideational." They think about ideas and look to religion for answers to most of the problems in their lives.

• They tend to be ideological. With unswerving certitude they accept the party line and do not critically assess the foundational ideas of the movement. They regard themselves as God's agents, and ascribe responsibility for their lives to Him. Personal success is a sign of God's approval; failures in life are divine tests. (A classic example: the pre-prison Jim Bakker justifying his luxurious lifestyle by insisting that God wanted him and wife Tammy to go first-class.)

• They take a proprietary attitude toward society, create a self-enclosed world, and hope that ultimately their ways will prevail. Working toward this end empowers fundamentalists with a sense of usefulness.

Consider, too, a few more features that were suggested by other scholars at the institute:

• Fundamentalists use insider language. As Visiting Fellow Bruce Lawrence notes, this gives them the feeling that they are in the right. For example, "humanist" used to be an acceptable term for a person who tried to understand human values. Under fundamentalism, "secular humanist" took on the meaning of anyone who is opposed to traditional religious interpretations. Visiting Fellow Bonnie Morris reports that the Brooklynbased Hasidic Jewish movement known as the Lubovichers use paramilitary terms to sharpen their selfimage as fighting the good fight against secular forces. Muslim fundamentalists, too, make language work for their cause, casting their endeavors as "holy wars" and their dead warriors as "glorious martyrs."

• They believe in scriptural purity. This is what Christian fundamentalists mean by the inerrancy of the Bible; it is divine revelation and therefore not open to individual interpretation. They reject the notion that the Bible is a collection of metaphors or that it is literature that can be critically read like any other text. Moslem fundamentalists take a similar view of the Koran.

According to many fundamentalist beliefs, ordinary men and women are not allowed to interpret the divine word, but a properly ordained imam, minister, or rebbe is expected to explain the holy books. That such exegesis is interpretation does not seem to trouble fundamentalists. Herein lies a major power base in fundamentalism: a leader can mobilize followers to do whatever he wants as long as he can convince them that he and they are under divine command. A less-than-godlike preacher can pull the wool over many a Godfearing eye, as the nation recently witnessed when the Bakkers fleeced their flock in golden style. Across the globe, the Ayatollah Khomeini commanded children to become martyrs for the holy war against Iraq, and the devout complied.

The divine certainty professed by fundamentalists is one of the magnets that attract many people into the fold. "People with certain temperaments and needs find fundamentalism particularly satisfying. Many people want a rebbe or priest or minister to tell them how to be," says Religion Professor Charles Stinson. "They want this kind of fixed clarity."

The sense of community that fundamentalists provide similarly attracts people who are fed up with the loneliness, isolation, and individualism that are commonplace in modern life. "Fundamentalist communities can be a cocoon, as in the self-chosen stable ghettos of Hasidism," notes Stinson. Lubovicher expert Bonnie Morris explains that the extended family feeling of the religious community holds great appeal for many of the women who enter the movement as adults. She tells of professionals who attained financial and career success in mainstream American life but found other fulfillment among the Lubovichers; "I used to be a psychiatrist till I met the rebbe," one such professional woman proclaimed as she attempted to proselytize other Jewish women into the community.

Of course, for people who grow up in fundamentalist communities, the cocoon provides protection from the outside world, but it also carefully controls metamorphosis into fundamentalist adulthood. Education among fundamentalists is the same as religious education. Creationism—creation science as it is now called—is a case in point. Fundamentalist parents do not want their children to be corrupted by the secular world.

This is an old theme in religion. Whereas some scholars argue that fundamentalism is a twentieth-century phenomenon, others see that fundamentalist movements have developed many times throughout history, as communities felt their way of lifeand their children's futures—to be threatened by outside influences. Religion Professor Reinhart argues that Islamic fundamentalist movements existed as long ago as the fourteenth century. He points out that Muslims, who were weakened by the Crusades of the early twelfth century and the Mongol invasions of the thirteenth century, redefined their Islamic culture and community through fundamentalist discourse during the 1300s. Muslims were not the only religious group to undergo fundamentalist surges during history. According to Albert Hourani, the kinds of questions about biblical interpretation thatoccupy Christian fundamentalists now were similarly divisive during the Reformation. He, Reinhart, and various other colleagues argue that the fundamentalist rejection of modernism has arisen in many different eras and places.

If fundamentalism is a recurring sociopolitical phenomenon, can we conclude that fundamentalists have more in common with each other than with the more liberal elements of their own denominations? Reinhart contends that fundamentalists view themselves as practicing the real Christianity or Islam or Judaism. To that extent, fundamentalists remove themselves from the wider denominational umbrella. Yet, whereas outsiders can find links between different fundamentalists, and fundamentalists from different denominations sometimes find themselves united over certain issues—school prayer or federal money for parochial schools, for example—it is doubtful that a Khomeini would recognize an Oral Roberts as a true brother. As Reinhart puts it, "Muslims say the Jews and Christians are imperfect versions of Islam. Jews say that the world is hostile and that they have to look out for themselves. Christians see Jews as failed Christians, and that, while it is good that Jews fulfill God's commandments, they nevertheless are bit-part players on the road to salvation."

What lies ahead for today's fundamentalists? Where pundits might rush in with pointed predictions about specific groups, the academics at the Humanities Institute, with characteristic prudence, hesitated to make pronouncements—although they offered some some out-loud thoughts. Hourani pondered whether Iran will be able to keep up the revolutionary steam without the charismatic energy of Khomeini. Stinson said he thinks that American fundamentalist influence peaked during the Reagan years. Even in the absence of firm predictions of trends and events, there is at least one certainty. As the institute scholars' work suggests—and we don't have to ask a rebbe or imam or minister for confirmation—as long as the flow of modernity laps up against religious traditionalists, there will be fundamentalists protecting and promoting their visions of divinity.

If fundamentalists are all of a kind, is Oral Roberts's dogma like that of the mullahs?

Khomeini proved that fundamentalist loyalty could move political mountains.

Karen Endicott is faculty editor of thismagazine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

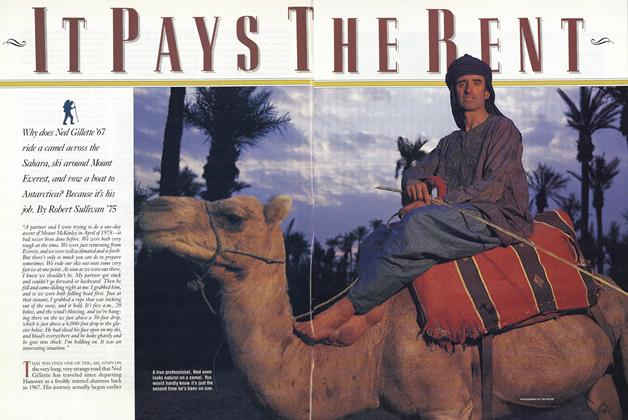

Cover StoryIt Pays The Rent

April 1990 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Article

ArticleA Few Of Dartmouth's Adventure Pros

April 1990 By Jim Collins '84, Andrew 's mother, Ed -

Article

ArticleOn chemistry, Cuba, and other radical elments on the campus.

April 1990 -

Article

ArticleThe Satanic Verses: Why Were Muslims So Offended?

April 1990 By A. Kevin Reinhart -

Article

ArticleA SENSE OF PLACE

April 1990 By Professor Jere Daniell '55, Joni B. Cole -

Class Notes

Class Notes1983

April 1990 By Kenneth M. Johnson

Karen Endicott

-

Feature

FeatureRooming with Style

NOVEMBER • 1987 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleA Hero in American Education

NOVEMBER 1989 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleProfessor of Economics William L. Baldwin

NOVEMBER 1992 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleMaking the Walls Talk

June 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleSlesnick by the Numbers

SEPTEMBER 1994 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleThe World's a Game

April 1995 By Karen Endicott

Features

-

Feature

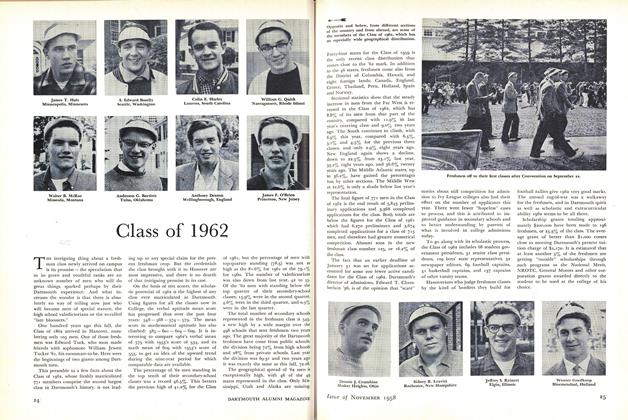

FeatureClass of 1962

-

Feature

FeatureTHE COLLEGE TEACHER: 1959

APRIL 1959 -

Feature

FeatureAn Astronaut's Words

July 1962 -

Cover Story

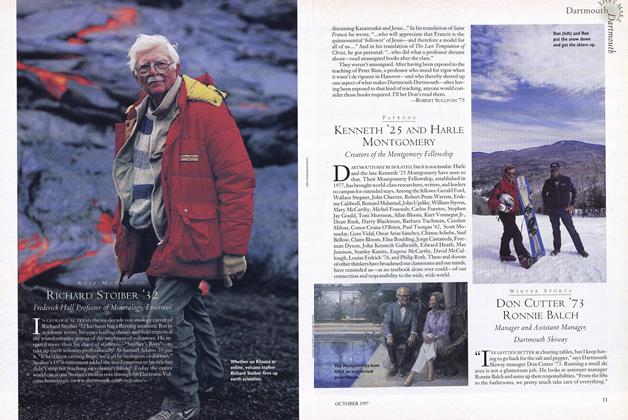

Cover StoryDon Cutter '73 Ronnie Balch

OCTOBER 1997 By Mark Schiffman '90 -

Feature

FeatureThe Commitment of Fellowship

November 1959 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY -

Cover Story

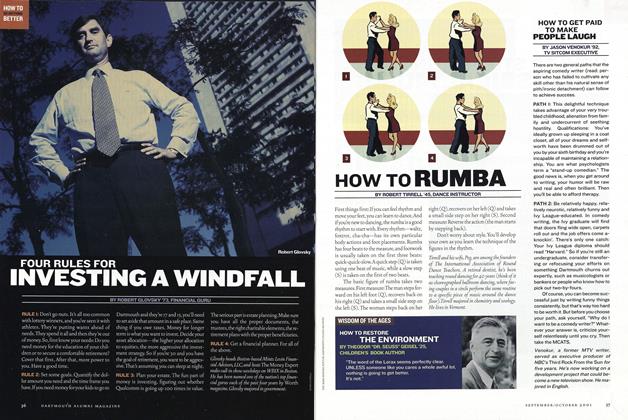

Cover StoryHOW TO RUMBA

Sept/Oct 2001 By ROBERT TIRRELL '45