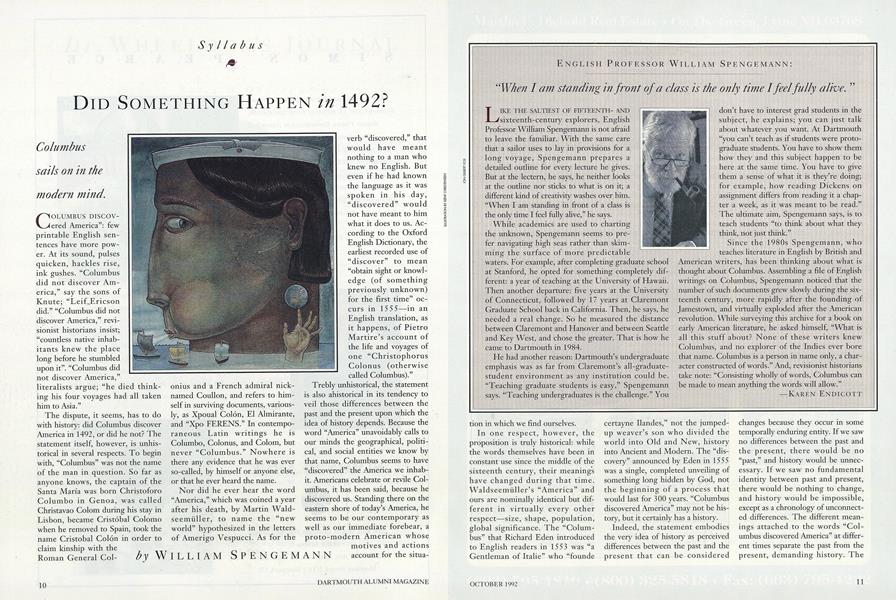

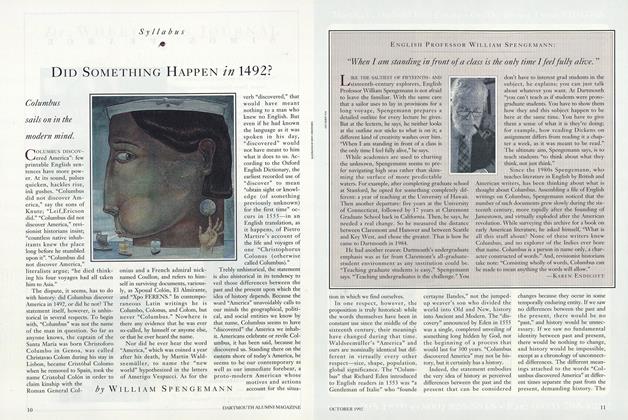

"When I am standing in front of a class is the only time I feel fully alive. "

LIKE THE SALTIEST OF FIFTEENTH- AND sixteenth-century explorers, English Professor William Spengemann is not afraid to leave the familiar. With the same care that a sailor uses to lay in provisions for a long voyage, Spengemann prepares a detailed outline for ever)" lecture he gives. But at the lectern, he says, he neither looks at the outline nor sticks to what is on it; a different kind of creativity washes over him. "When I am standing in front of a class is the only time I feel fully alive," he says.

While academics are used to charting the unknown, Spengemann seems to prefer navigating high seas rather than skimming the: surface of more predictable waters. For example, after completing graduate school at Stanford, he opted for something completely different: a year of teaching at the University of Hawaii. Then another departure: five years at the University of Connecticut, followed by 17 years at Claremont Graduate School back in California. Then, he says, he needed a real change. So he measured the distance between Claremont and Hanover and between Seatde and Key West, and chose the greater. That is how he

He had another reason: Dartmouth's undergraduate emphasis was as far from Claremont's all-graduatestudent environment as any institution could be. "Teaching graduate students is easy," Spengemann says. "Teaching undergraduates is the challenge." You don't have to interest grad students in the subject, he explains; you can just talk about whatever you want. At Dartmouth "you can't teach as if students were protograduate students. You have to show them how they and this subject happen to be here at the same time. You have to give them a sense of what it is they're doing; for example, how reading Dickens on assignment differs from reading it a chapter a week, as it was meant to be read." The ultimate aim, Spengemann says, is to teach students "to think about what they think, not just think."

Since the 1980s Spengemann, who teaches literature in English by British and American writers, has been thinking abcrat what is thought about Columbus. Assembling a file of English writings on Columbus, Spengemann noticed that the number of such documents grew slowly during the sixteenth century, more rapidly after the founding of Jamestown, and virtually exploded after the American revolution. While surveying this archive for a book on early American literature, he asked himself, "What is all this stuff about? None of these writers knew Columbus, and no explorer of the Indies ever bore that name. Columbus is a person in name only, a character constructed of words." And, revisionist historians take note: "Consisting wholly of words, Columbus can be made to mean anything the words will allow."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

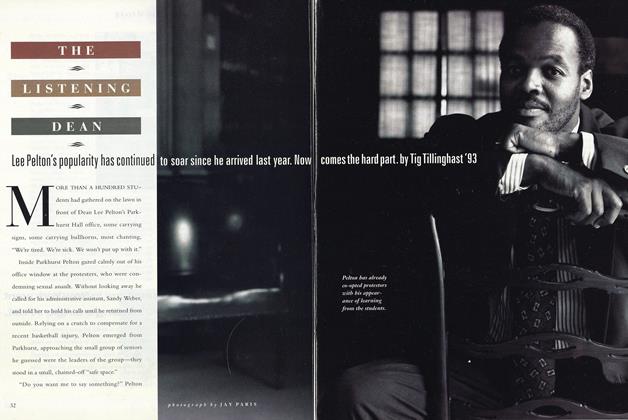

FeatureTHE LISTENING DEAN

October 1992 -

Cover Story

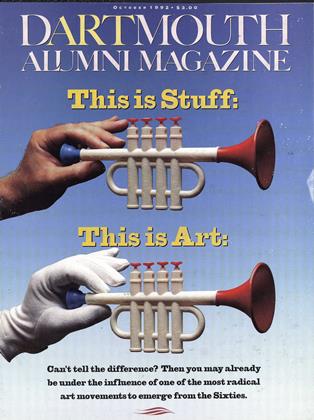

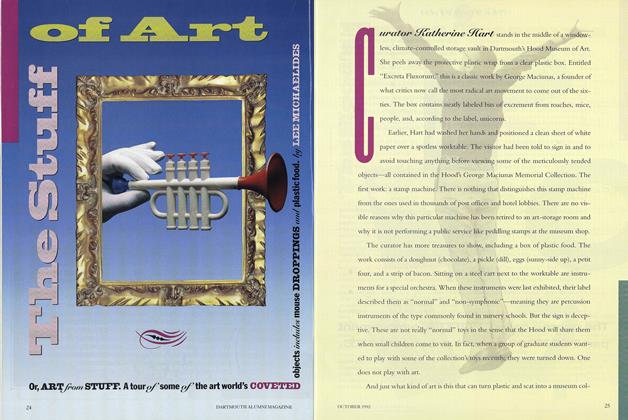

Cover StoryThe Stuff of Art

October 1992 By LEE MICHAELIDES -

Feature

FeatureThe Underground Curriculum

October 1992 By Tim Brookes -

Article

ArticleThe Lost Season

October 1992 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

Article

ArticleDid Something Happen in 1492?

October 1992 By William Spengemann -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

October 1992 By "E. Wheelock"

Karen Endicott

-

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

MAY • 1988 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleHold that Curriculum

June 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorYou could say a woman started it all.

MARCH 1997 By Karen Endicott -

Feature

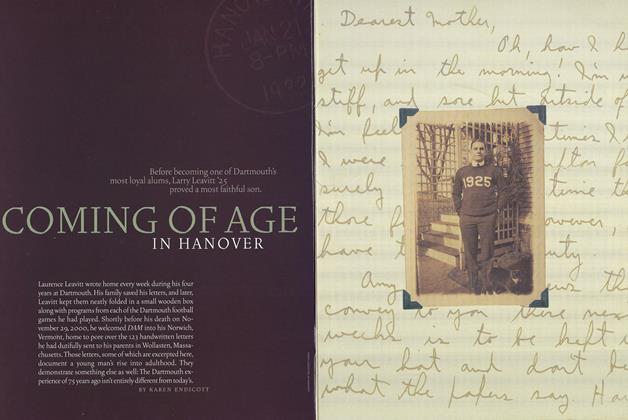

FeatureComing of Age in Hanover

Nov/Dec 2001 By KAREN ENDICOTT -

Article

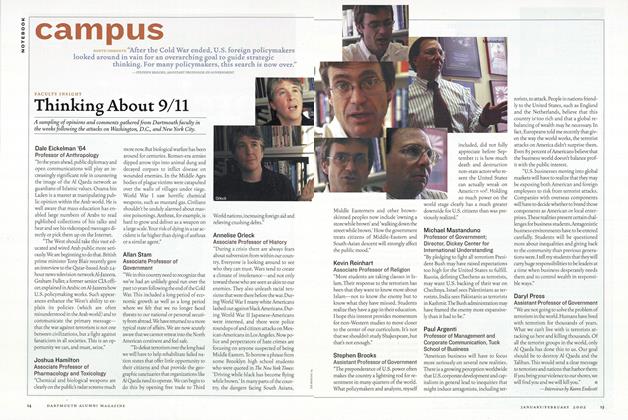

ArticleThinking About 9/11

Jan/Feb 2002 By Karen Endicott -

Article

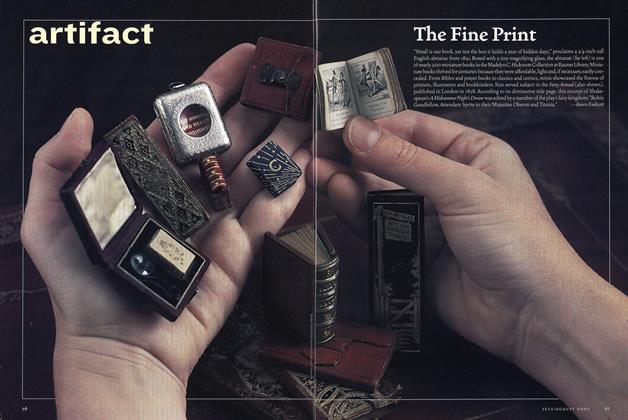

ArticleThe Fine Print

July/Aug 2002 By Karen Endicott

Article

-

Article

ArticleDR. PATTEN TO COLLECT SCORPIONS IN COSTA RICA

February 1921 -

Article

ArticleWith the Outing Club

December 1940 -

Article

Article1966 Football Forecast

JULY 1966 -

Article

ArticleSports Schedule

MAY 1968 By ALBERT C. JONES '66 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

May 1953 By Richard C. Cahn '53 -

Article

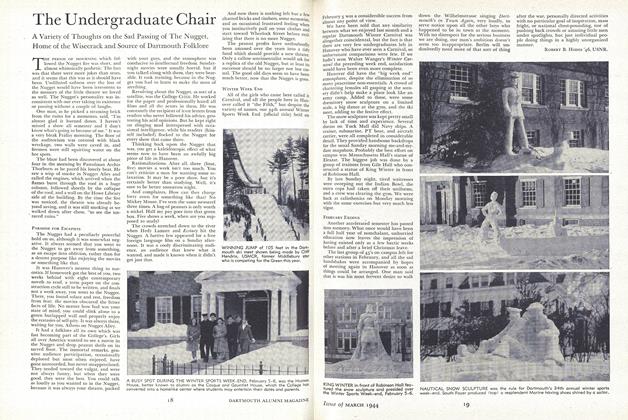

ArticlePARADISE FOR ESCAPISTS

March 1944 By Robert B. Hodes '46, USNR