JORGE HERNANDEZ Martin, assistant professor of Spanish, knows precisely when the rainforest became part of his reality. He was in Ithaca, New York, at Cornell, writing about detective fiction for his doctorate in Romance languages. "In 1987 I was busy writing a dissertation on a theme unrelated to anything tropical," he says. "But that summer Brazilian scientists estimated that the amount of Amazonian forest burned was 77,000 square miles. I recall the commentator of the nature program saying, 'an area one and a half times the size of New York State.' 'There' became very much 'here' for me at that moment. The imaginary superimposition had worked, at least on me; I wrote a note to myself to check how the writers of Latin America had incorporated the rainforest into their concerns, and how they had thematized the forest into the various national literatures."

What took root at Cornell has borne fruit at Dartmouth: Since coming to the College in 1989 Hernandez Martin has not only looked at rainforest literature; he has made it the substance of a freshman seminar in which he makes the faraway immediate.

But then, linking here and there seems to be second nature for Hernandez Martin, who has experienced more than his share of relocations and discontinuities. Raised in Cuba, at age 12 he was sent to Spain, where he stayed for two years. By the time he rejoined his family in their new home in Anaheim, California, in the shadow of Disneyland's Matterhorn, he had already had plenty of time to contemplate place, home, roots, and rootlessness. In Spain he had taken solace in books "books create place," he says and in his friendships with other transplanted Cubans. He found that "the most important places are where you interact with others. Dialogue creates a sense of home."

Even Hernandez Martin's interest in detective fiction, which he'll be teaching next year, brings him face to face with questions of place. In mysteries such as Umberto Eco's The Name of the Rose, "you have to think about time—when you learned what you know," he explains. "You also have to think about what the setting is hiding."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Dartmouth Murder Mystery Mystery

June 1992 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

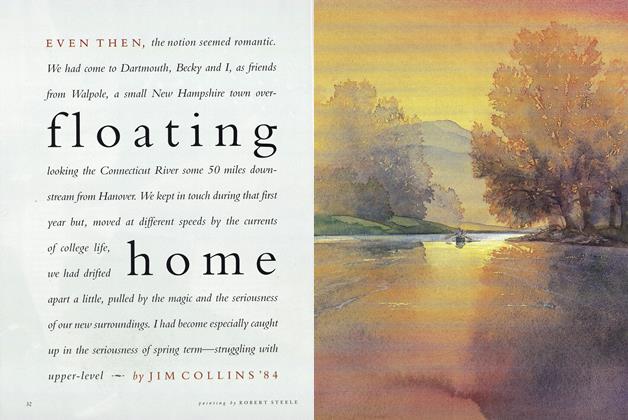

FeatureFloating Home

June 1992 By Jim Collins '84 -

Feature

FeatureLast Person Rural

June 1992 By Noel Perrin -

Feature

FeatureThe Woman Who Was Not All There

June 1992 By Paula Sharp '79 -

Feature

FeatureWhy in The World: Adventures in Geograhy

June 1992 By George J. Demko with Jerome Agel and Eugene Boe -

Feature

FeatureMurder on Wheels

June 1992 By Valerie Frankel '87

Karen Endicott

-

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH AUTHORS

OCTOBER 1988 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleThe Anthropology of Freshman Trips

NOVEMBER 1989 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleProfessor of Economics William L. Baldwin

NOVEMBER 1992 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleOut of the Literary Closet

NOVEMBER 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleA Cautionary Tale

April 1995 By Karen Endicott -

Classroom

ClassroomThe Art and Science of Group Dynamics

Nov/Dec 2002 By Karen Endicott

Article

-

Article

ArticleAlumni Carnival

February 1935 -

Article

ArticleDean Bill Honored

June 1935 -

Article

ArticleThe Coming Month

January 1955 -

Article

ArticleFoundation Honors Years of Work for Poland

December 1956 -

Article

ArticleCatching Up with Evie Petot '22

May 1960 By JACK CHILDS '09 -

Article

ArticleProsecutor of Nazis

February 1946 By KEN HILL '25