THE DEAN of rock critics is evenolder than MICK JAGGER. Now he mustcome to terms with DEATH METAL.

OK, says Robert Christgau, darting toward his study with a cassette tape clutched in one fist. "I'm going to work." He pops in the tape, and a lone speaker out in the cluttered dining room emits the jangling, screeching strains of some unidentified, unknown, possibly great but probably mediocre rock band. Most people wait until after work to check out a new tape. As the "dean of American rock critics," and veteran music writer for the Village Voice, Christgau spends his working days and many evenings—most of his life, in fact listening to rock and roll music. Demographically, the 51-year-old Christgau ought to be grooving to "Sister Goldenhair" on his local Lite-rock station, but he can still tell Ice Cube from Ice-T. (Of the two, he prefers Ice-T.) But keeping abreast of popular music, as it fragments into a zillion genres and sub-genres, from speed-metal to gangster rap to country punk, demands more and more of Christgau—even "working" during dinner, if need be. For two and a half decades, Christgau has been America's most voracious consumer of rock and roll, and the job isn't getting any easier.

He is giving me the inside poop on this band when his seven-year-old daughter, Nina, appears in the doorway.

"Daddy! Daaaa Deeeee!! I want to listen to music I like!"

So much for work. The tape comes out, and Christgau rifles through a stack of CDs on the floor until he finds a B-52s best- of. "Hey, Nina, do you want to go see the B-52s with me, on August 19th in Poughkeepsie?"

Nina nods yes.

"What's it like being a rock critic's daughter?"

"Fun!"

"She's always had good taste," says Christgau, the proud father. Adds his wife, Carola, a video critic, "She turned us on to the Go-Betweens."

"A great record," avers Christgau, who would have dismissed the Go-Betweens had his daughter not taken a shine to them. "She's always had good taste; she never had a Raffi tape, ever."

"Party!" whoops B-52 Fred Schneider. "Party out of bounds!"

ROCK AROUNDTHE CLOCK

THE APARTMENT, A TWO- bedroom East Village coop where Christgau has lived since 1975, is in a state of functional chaos. The front door barely opens halfway before thudding against a bundle of winter coats. Unrecycled beer bottles are stacked in the hall, and the dining room is strewn with books, toys, and envelopes with important-looking phone messages scribbled on them. Skyscrapers of dishes rise in the tiny kitchen, a hula hoop hangs over a door, and one can hardly take a step without upsetting a stack of CDs or a cat-food dish.

As we await a delivery of Thai food, Christgau pulls up a chair and pours himself a whiskey. A little later, a ringing phone prompts a minor crisis. Where is it? After a moment's doubt, Christgau dives into his office and emerges triumphant, red desk phone in hand.

But the line is dead. Since he got into this work 25 years ago, Christgau apparently hasn't had a lot of free time in which to tidy up. But that's understandable, because rock and roll never takes a vacation. Each week the mailman deposits another 30 or 40 new discs in his post-office box, a flood tide of pop culture that Christgau must wade through. A typical day begins with five discs in the CD changer, which is programmed to play only the first three cuts of each. Obvious losers go to the reject pile, but most return to the changer for a second chance.

Every month he capsule-reviews a couple dozen of the most noteworthy efforts in his "Consumer Guide" column, a fixture in the Voice since 1969. His capsules are dense, witty, insightful and sometimes profane little nuggets of prose, rarely exceeding 200 words. What makes the job seem a lot like work is the sad fact that most rock musicians spend their careers on the wrong side of what Spinal Tap's Nigel Tufnel called the "thin line between stupid and clever." And there are so damn many of them. Compact discs line the flat's L-shaped hallway, the Replacements not far from Sonny Rollins, and a dozen obscure bands in between. The study is stuffed with LPs, cassettes, and still more discs, leaving just enough space for Christgau to wedge himself in front of his personal computer. These are just the keepers. For the rest, nearly three decades' worth, he says, "I have a warehouse."

What irks many people about Christgau is his practice, adopted in the late 19605, of assigning to each record a letter grade, from A+ ("an organically conceived masterpiece that repays prolonged listening with new excitement and insight") to E- (causes "a sense of horror in the face of the void"). These days, magazines like Entertainment Weekly grade everything in sight, but in 1969, Christgau's schoolmarmish conceit sort of, you know, chilled the whole grooviness of the scene. Lou Reed once took him to task for it. "It was my way of thumbing my nose at the counterculture," Christgau says. "If you're going to put a price on it, I'm going to put a letter on it." One forgotten record from the seventies, unfortunately titled A Plus, earned a one-word pan: "Wrong."

His career has spanned hundreds of columns and two comprehensive books covering the decades of the seventies and eighties, a massive report card on rock and roll. From the worthless to the classic, the instantly forgettable to the unjustly forgotten, hardly a single significant effort has escaped his sharp, polemical phrasings, or his arbitrary, infuriating letter grades. Don't try to tell him that The Wall Street Journal pronounced rock officially dead last summer. "Rock is slowly fading as tastes in music go off in many directions," the headline declared. Christgau has heard this one before. The "rock is dead" story has resurfaced with Zodiacal regularity almost since rock was born. Esquire asked Christgau to write it early in his career, and he wisely refused. What would he have done with the rest of his life?

Besides, to this day, the report of rock's death seems greatly exaggerated. Rock lives by splintering, recombining, metastasizing. This isn't rock's problem, but it is very much Robert Christgau's problem.

"Rock isn't dying," Christgau wrote in the early 19705, when he was barely 30. "And neither am I." Lamusique, c'est moi.

Fear of Music

R OCK AND ROLL CRITICS could never be confused with rock stars. In print, Christgau comes across as flamboyant and engaging as Jagger himself, sneering, snarling, and strutting his stuff. In person, shuffling around his apartment in his thick glasses and sagging khakis and worn running shoes, he resembles a rather sleepy owl (another beast who lives or dies by its ears). But rock and roll " critics are also different from rock fans, and not just because they get their compact discs for free. Christgau long ago lost the fan's relationship to music; self-denial is part of the job description. "One of the great regrets of my protfessional life is that I don't have enough time to listen to things I really like," he says.

Tonight he makes an exception; after dinner, the dense chords of The- lonious Monk's Brilliant Comers bounce out of the living-room speakers. "One of my five favorite albums of all time, no question about it," he sighs. "Probably, my favorite record of all time."

For Christgau, Brilliant Corners was a telling way station between his early passion for Pete Seeger-style folk music (he's a lifelong political radical) and his later love for the Sex Pistols, Run-DMC, and the rest. "I was originally a folkie," he says. "And then, when Joan Baez came along, I switched to jazz—immediately." He laughs. "I had always listened to jazz as well, and I gradually got better at it."

Got better at it. To Christgau, listening is a skill. And jazz honed his listening chops in ways that rock circa 1965 never could have. Jazz taught him to listen for the elements of rhythm, energy, pace, and lyricism that add up to "an organically conceived masterpiece."

God help you if you try to listen to BrilliantCorners back to back with a slightly later Christgau fave—say, the New York Dolls, the raucous, legendary band Christgau and others cite as the founding fathers of American punk ("Could you make it with Frankenstein?" they wonder). Or Randy Newman's 12 Songs, another A+. But then, we all have our favorite records, from the CD we bought last week and haven't taken off the Yamaha yet to an old vinyl album that evokes, forever, a certain stage of our emotional or intellectual lives, a memorable experience, or some really dumb thing we did. Then there are those embarrassing old things from our youth that we'd just as soon not have our friends know about. (Confession: I still think Saturday NightFever was a pretty good record. Half of it, anyway and stop laughing: Christgau gave it a B+.)

So there's no accounting for taste, right? Well, wrong. Some people's tastes are more equal than others. What distinguishes Christgau and his fellow critics from the common herd is an unshakable belief that their musical opinions are somehow right. Robert Christgau's criteria are simple: What Robert Christgau likes is good. What Robert Christgau doesn't like is bad. "It's a simple empirical matter. I'm sufficiently good—my sensibilityis sufficiently broad, I'm good at screening out bullshit, and screening out the irrelevant in my own response that a number of people seem to find that I have what is called in the industry 'good ears.' I don't have any formal knowledge of music, but I have good ears." Good ears?

"I know music that other people are going to like; I am reliable. A number of critics are not reliable listeners. They'll consistently like records that they will swear to the high heavens are great records, only nobody else likes those records."

To test this proposition, I went out and bought The New York Dolls ($8.98 in the cut-out bin). A great rock and roll record, for sure; make that, a great New York rock and roll record. But something short of a masterpiece—but what do I know?

CH-CH-CH-CH-CHANGES

IN 1958, A SKINNY 16-YEAR-OLD with near-perfect boards named Robert Christgau left the asphalt plains of Queens for Dartmouth. Armed with a full scholarship, he dreamt not of rock and roll but of law school. Articulate, polemical, and just a tad arrogant, Christgau would have made a splendid lawyer. Rock critics hadn't even been invented yet, while lawyers had been around for centuries.

In fact, 1958 was the year Billboard magazine first pronounced rock dead; at isolated, homogenous, all-male Dartmouth, it really was. But Dartmouth, more than any other influence in his life, formed Christgau as a critic and writer. Even though he kind of hated it.

Young for his class, so far from his girlfriend in New York, and still so close to his religious, lower-middleclass background, Christgau didn't click with the sophisticated prepschool crowd that dominated the campus at the time. He subscribed to the Village Voice; he never joined a fraternity. By the end, he was hitchhiking to New York every weekend and learning to love pop music by exposure to AM radio.

Contemporaries remember Christgau as a congenitally messy quasi-bohemian who seemed to live the life of a character from The Dharma Bums. His worldly possessions consisted of a mattress on the floor, a few sweatshirts and jeans, and a crate of books. A vociferous and frequent interjector in his English classes, he was close to few of his fellow students. And he claims actually to have meant what he told his admissions interviewer about wanting to learn. "I was a real nerd," he says. "I wasn't cool. Unlike the bohemians around there I didn't come from a minority background, so I wasn't really a bohemian. I hung out on the fringes. My friends at Dartmouth were weirdoes...I knew a 1 ot of weirdoes. A lot of gays, actually, a lot of in-the-closet gays. I think about some of these people, and I mean, I never thought they were, at the time. They were."

It was a freshman English class taught by John Hurd that finally dislodged Christgau's legal ambitions. "There was very little reading, you just dissected short stories. It changed my life—taught me about art. And from then on, I wanted to be a writer." At the same time, Christgau took Philosophy 1, "which destroyed what little remained of my religious faith, and plunged me into a state of existential despair that lasted two years. I mean, I was in real despair for two years." He graduated from Dartmouth a pagan, something his family was not quite prepared to accept. The Christgaus were evangelical Christians. His father, a New York City fireman, graduated from NYU night school a year before Christgau finished Dartmouth. "All those experiences, it turned me into an atheist, made me a different person, who they were not prepared for at all. I mean, they blame Dartmouth for what happened to me."

The TV in the next room, where Nina and Carola have just begun to watch a movie, interrupts. It says, "I am tired of going to the funerals of black men who have been killed by white men!" Wrong tape.

Christgau resumes: "It would have happened anyway, only I wouldn't be quite so well off."

Perhaps Christgau's latent paganism would have surfaced, but it was the Dartmouth English Department, and the New Criticism it preached circa 1960, that formed Christgau as a critic. "I was always a critic," he says. "Didn't want to be—I wanted to be a creative person, but criticism is where I ended up, and it's what I learned at Dartmouth."

New Criticism was a school of aesthetics that held that an art object is most meaningful on its own; cultural and historical references, and even its author, are mere distractions. "I learned it, and by the time I was finished, I had decided that it was a load of shit. It was a religion. But very polemically speaking, it was very important... I've spent the rest of my life arguing with it."

At the very least, this explains a certain detachment in Christgau's work: He reviews records, but he rarely interviews rock and rollers. And he regularly trashes—or worse, ignores—albums and artists that have been hyped to the high heavens, notably Springsteen's recent doublecomeback, which he dismissed in exactly four words. All that matters is what's on the wax—or whatever CDs are made of.

WELCOME TO THE WORKING WEEK

CHRISTGAU DIDN'T FIND his vocation; he waited for it to find him. When he returned to New York in 1962, cum laude bachelor's in hand, he cherished ambitions of becoming a novelist, like many people who end up in journalism or criticism. He settled for a file-clerk job in an investment house and struggled at night with his fiction.

New York in 1962 was close to a bohemian paradise. Garret apartments on Avenue B rented for $60 a month, Thelonious Monk played at the Blue Note, and the art world was hopping. The filing job was nothing to put on the resume, but simply living in New York proved to be an essential, formative experience.

What really launched Christgau as a critic was exposure to Pop Art, which said, in effect, that the banal and mundane artifacts of daily life—Brillo pads and all that—are as worthy of scrutiny as highfalutin masterpieces. "The crucial Pop Art experience was going to a show by Tom Wesselman, not a well-remembered artist. I walked in to the Greene gallery and I heard Frankie Valli singing 'V-A-C-A-T-I- O-N.' I looked in the office, and there was no radio in the office. Then I found the painting, and the radio was in the painting, tuned to WABC. And I thought, aha."

If Wesselman s painting of a bland suburban homescape was art, then that made Frankie Valli, um, an artist.

And it made Christgau a critic, only he didn't realize it yet. Over the next couple of years he hitchhiked around the country, then took a series of low-end police reporter jobs, one of which yielded his first big break. In 1965, at the tender age of 23, he published a feature in New York magazine about a young woman who starved to death on a macrobiotic diet. "Beth Ann and Macrobioticism" was later anthologized in Tom Wolfe's The New journalism, but it is taut and focused and free of new-journalistic excesses—rather like the subject of his still-unwritten senior thesis, Ernest Hemingway.

New Journalism gave way to criticism when Christgau snared a gig writing about popular music for Esquire in 1967. That ended two years later, when he wouldn't do the rock-is-dead piece, so Christgau moved to the Village Voice and took over as its music editor. "They didn't even look at a clip," he says.

Anybody could do it in those days; the game was wide open and there were no rules, yet. "I'm a writer, baby," he told a female interviewer from the Long Island Star-Journal in 1967. "No one who writes about music knows much about it. Music is a sociological phenomenon."

Christgau tried to be a sociological phenomenon, too. In a 1971 Dartmouth questionnaire he listed his profession as "Hippie." Hardly: that was the year Newsday hired him away from the Voice for the then-princely salary of $16,000. (That's still pretty good, for a writer.)

By 1971, rock criticism was becoming established as a vocation, as even suburban newspapers like Newsday felt the need to get with it. The profession had gotten a lot more competitive, too, with critics from the Voice, Rolling Stone, Creem, and a few real hippie magazines (ever read Crawdaddy?) sparring endlessly in print. There was something happening, and Christgau and his contemporaries made it their business to tell everyone else what it was.

All of a sudden, it seemed, Christgau shot above the fray with a new title: he became the "dean of American rock critics."

How, you might wonder, did he acquire this honorific (which is emblazoned across both of his recordguide books)?

He appointed himself, flippantly yet seriously, at a cocktail party: "Someone didn't know who I was, so I said, 'l'm the dean of American rock critics,"' he laughs. "The position was not only vacant; it had never been imagined."

Hey, HEY, My, MY

THE TITLE FITS THE PROFESsorial Christgau better now than ever, if only because he has outlasted most of his peers. The great gonzo rock journalist Lester Bangs is dead, and old hands like Jon Landau and Richard Meltzer no longer match Christgau's prolific output. Greil Marcus recently wondered in Esquire whether rock is dead; almost, he decided. The music pages of the Village Voice, where Christgau returned in 1974, are dominated by writers who wore diapers when he first published there.

Which raises a touchy question. How does a 50-year-old maintain interest in a music whose primary consumers are half his age, or less? He belongs to the same generation as rock's senior citizens—toward whom he shows precious little sympathy (calling Peter Townshend "that horri- ble old fart," for example). The only old-time rocker Christgau still seems to like is Neil Young (who, by the way, is three years Christgau's junior). You know, the guy who warbled, "Rock and roll will never die." Plus, being a daddy makes it harder to hang out at CBGB's.

For most people at least, a certain ossification of the ear seems to set in around age 25. Christgau denies he is one of those people. "I admit to no hardening of the tympanum," he wrote in 1990. On the other hand, he shows signs of disquietude with mainstream rock product. He all but ignores the legions of independentlabel ("indie") bands that came to dominate college radio in the eighties. Instead, Christgau prowls the fringes of popular music. In the seventies, he once wrote, "Not all of the most popular rock was good, but most of the good rock seemed to be popular."

That's not as true now. To be a critic today means to be an explorer. He has taken extended safaris into the music of Africa, the Caribbean, and Latin America—precisely because it is more challenging than American pop. Of the 20-plus discs surveyed in one recent column, only two or three were by North American artists. The rest were West African, Caribbean, or Asian. So is he bored with rock? Ditching the canon?

"If there's anyone who's creating a canon," he retorts, "and I'm not sure there is, it's me."

That canon, if there is one, is getting harder to find. In 1972, rock music pretended to be art, and the results were often excruciating. In 1993, music is about identity: metalhead, hardcore punk, hiphopster, skater. Buy the music, wear the clothes, join the tribe. "Every quiddity of taste is now serviced," Christgau says. "For me, that's been the story." The hard part is keeping up with it all.

The Wall Street Journal mistook rock's fragmentation for its death. Fewer people are buying "rock" records, it said, while rap and even country music sales boom. But that depends on what you call a rock record. The Journal's own charts showed overall pop-music sales continuing to soar, including country, rap, and rock. How do you separate hip-hop from rock? In which category do you place Ice-T, the rapper who fronts a heavy-metal band?

Another recent Christgau column illustrates, unintentionally, rock and roll's new Catholicism. He reviewed rappers FU-Schnickens, the danceclub act Deee-Lite, Monty Python Sings, grunge-rock kings Sonic Youth, Senegal's Youssou N'Dour (of which he opined, "the arranged rock song now seems beyond the reach of white men"), and an outfit from Zaire called Diblo Dibala & Matchatcha. All rated between B+ and A. But here's the catch: the rap audience of FU-Schnickens might never even meet any Sonic Youth fans; Deee-Lite buffs might cross tracks with Diblo Dibala aficionados, but only on the freeway

There are many constellations and galaxies in the rock and roll universe now, all speeding away from each other like remnants of some cultural Big Bang. Has this universe gotten too big for one man to cover?

THIS REALLY ISSPINAL TAP

EVEN IF THE WALL STREET Journal and other cultural arbiters have consistently been wrong about rock's death, popular music has undergone a series of seismic shifts over the years, the biggest being the advent of punk in 1976, and rap in 1980. Now heavy metal is hot, especially a variety known as death metal. At 50, Christgau admits that it's not easy to like. Heavy metal, he says, reminds him much of classical music. "The symphony is about power," he declares. "That's what its ideology is: an ideology of power and control."

He felt the same way about Black Sabbath, the seminal metal band from the 19705. Two decades ago, Christgau condemned the Sab's debut effort as "pure adolescent hostility." But now Black Sabbath has reunited(!), and Christgau finds himself having to play catch-up.

Death metal takes a little getting used to, he says, in the understatement of the evening. We're trudging down Second Avenue in the rain; at 11 p.m., Christgau has decided to get a haircut. "Both rap and African music, which are the things that got me through the eighties, those were not things that I had to try to like," he continues. "Those were things I couldn't resist—loved the moment I heard them. But not metal. I've never liked metal. I hated the first Black Sabbath record the first time I ever heard it, gave it a D, before I had any idea that it was gonna have any importance whatsoever. And when I was doing the seventies ConsumerGuide, I ended up listening to all those records again, and I still hated them! I liked Motorhead, I liked Aerosmith; but not Sabbath. What turned me off were, I think, its pretensions to grandeur, and it's an enactment of a certain kind of male power."

But over the summer, much of which he spent at a rented country house in the Catskills with his family, Christgau experienced a conversion of sorts. He came to terms with death metal.

"I find myself pretty amused, intrigued by a lot of the new metal. It's a recent feeling that hasn't really jelled. But there's a band called 'Old'—I couldn't resist a band called Old. They were really funny."

As he enters his sixth decade, Christgau has grown particularly fond of a death-metal band called Deicide, because it is "intentionally outrageous. They can't be doing this literally. They want you to delight in their own outrageousness." Which is the whole point, after all.

This organis one of thenation's mostvoraciousconsumers ofrock and roll.

John Hurd'sEnglish classdislodgedhis legalambitions.

Christgau was a"nerd" in college.

Christgau called PeterTownsend an old fart.

Neil Young is the onlyold-time rocker he likes.

1958 was the year Billboardmagazinefirst pronouncedrock dead;at isolated,homogenous,all-maleDartmouth,it really was.

Rock lives bysplintering,recombining,metastasizing. Thisisn't rock'sproblem, butit is verymuch Robert Christgau'sproblem.

Heavy metal, he says,remindshim toomuch ofclassicalmusic.

BILL GIFFORD is associate editor ofthe Washington City Paper. He stillhates death metal.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

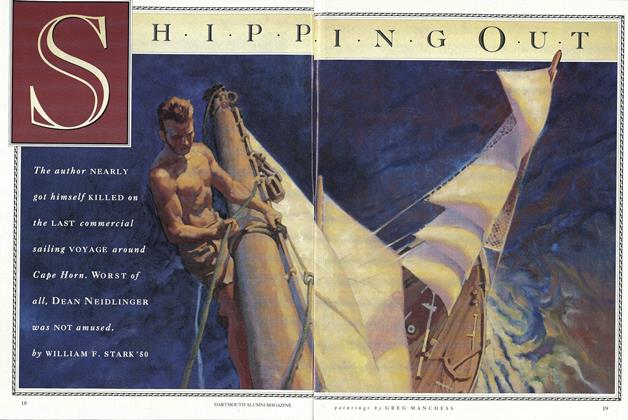

FeatureShipping Out

April 1993 By WILLIAM F. STARK '50 -

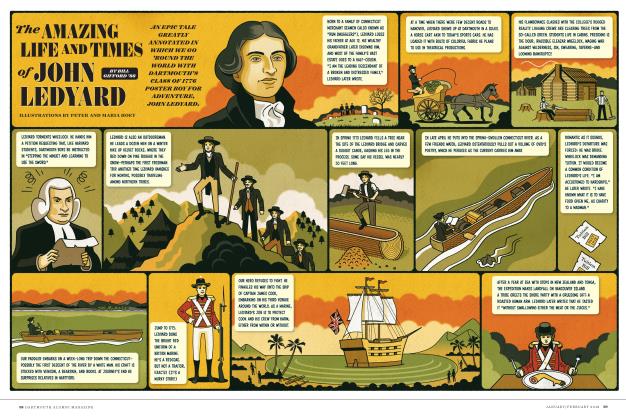

Cover Story

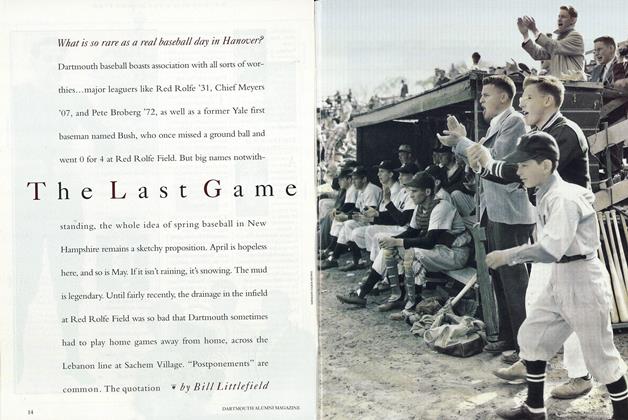

Cover StoryThe Last Game

April 1993 By Bill Littlefield -

Feature

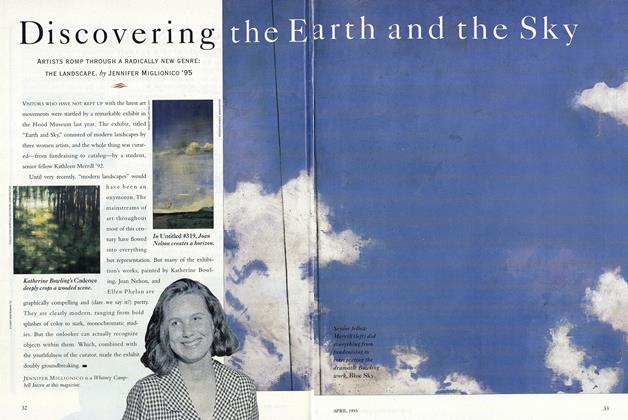

FeatureDiscovering the Earth and the Sky

April 1993 By Jennifer Miglionico '95 -

Article

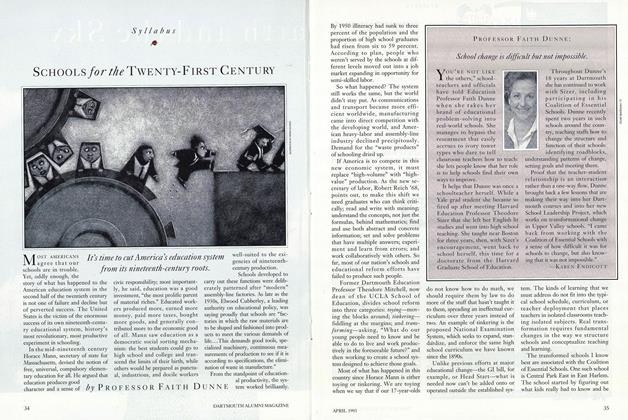

ArticleSchools for the Twenty-First Century

April 1993 By Professor Faith Dunne -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

April 1993 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleNothing Less Than a Hero

April 1993 By James O. Freedman

BILL GIFFORD '88

Features

-

Feature

FeatureTHE WHEELOCK SUCCESSION

DECEMBER 1969 -

Feature

FeatureArcheological "Amateur"

October 1973 -

Feature

Feature... AND MANY DARTMOUTH YESTERDAYS

October 1961 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Feature

FeatureThe Draft: To Register or Not to Register

NOVEMBER 1984 By James Heffernan -

Cover Story

Cover StoryAs We See It

JUNE 1999 By Julian Okwu '87 -

Feature

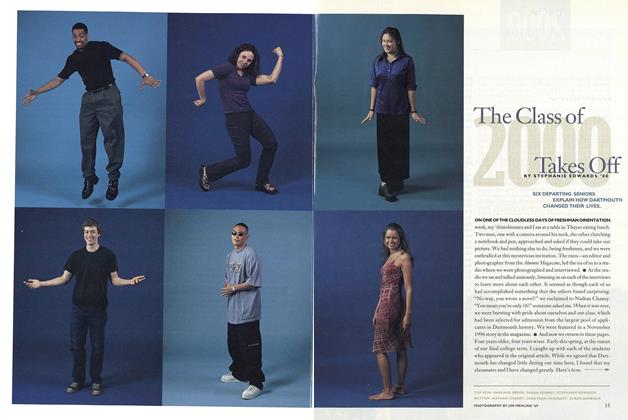

FeatureThe Class of 2000 Takes Off

JUNE 2000 By STEPHANIE EDWARDS ’00