The White Mountains, nude swimming, a shot in the dark...what more could life hold in store?

Nborth woodstock, new HAMPSHIRE, lies near the top of the Merrimack River's 5,000-square-mile watershed at the confluence of the two main branches of the Pemigewasset River. Just south of Franconia Notch, it is a laundry run 12 miles and 1,500 vertical feet down the mountain from the Moosilauke Ravine Lodge, where I happened to be working during the summer of 1981. Swelled by the weekend skier and tourist influx from the south, the town is the exit off 93 leading to landmarks both inimitable and pedestrian. Mt. Lafayette and the Pemigewasset Wilderness. Cannon Cliffs and the Old Man of the Mountains. Indian Head. Whale's Tail Water Park. Candy Land. Dad's Restaurant and Lounge.

Dartmouth students eventually encounter, as I did, varied Dartmouth haunts in this corner of the White Mountains. Mt. Moosilauke, of course, and its Ravine Lodge. The Outing Club's Aggassiz Cabin. The Loon Mountain legacy left by the late New Hampshire Governor Sherman Adams '20. Clark's Trained Bears (where Dartmouth skiers would yell from the team bus as it passed, "FREE THE BEARS!" to confused ' tourists who were running fish up zip lines to bears chained atop a tall platform).

But on the evening of Friday, July 10, North Woodstock felt like a small-town, sleepy backwater of a place. I drove down the mountain from the Ravine Lodge after dinner that night to do laundry, accompanied by fellow lodge crew workers Jim Wells '81 and '84s Ingeborg Sacksen, Viva Hardigg, and Barb Rollins. While we waited for our clothes, as usual, we ran through North Woodstock's limited list of evening activities. You could spend just so many quarters in the Wash Works Laundry giving "dryer rides" to those who fit into the machines, and staying for one beer at Truant's Taverne, the local watering hole, left most people's thirst for night life more than sated.

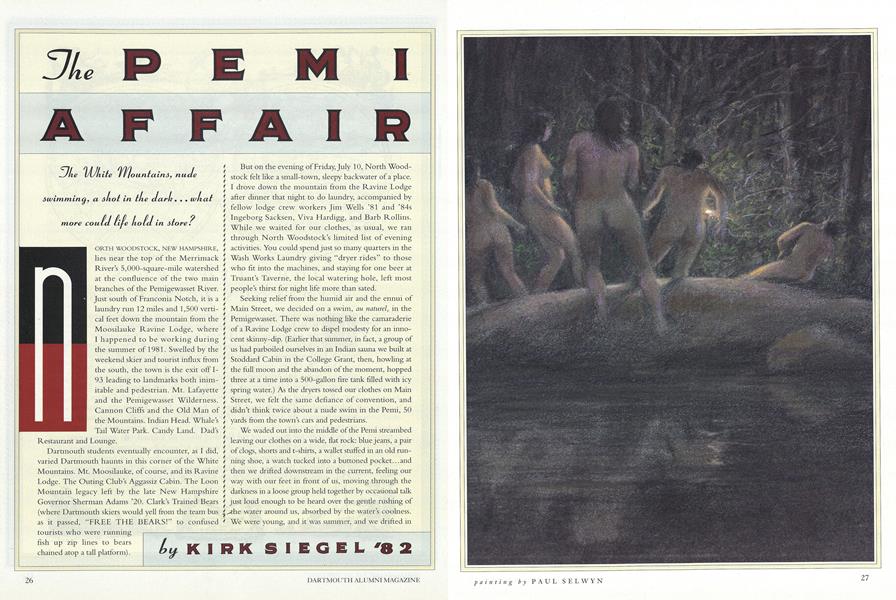

Seeking relief from the humid air and the ennui of Main Street, we decided on a swim, an naturel, in the Pemigewasset. There was nothing like the camaraderie of a Ravine Lodge crew to dispel modesty for an innocent skinny-dip. (Earlier that summer, in fact, a group of us had parboiled ourselves in an Indian sauna we built at Stoddard Cabin in the College Grant, then, howling at the full moon and the abandon of the moment, hopped three at a time into a 500-gallon fire tank filled with icy spring water.) As the dryers tossed our clothes on Main Street, we felt the same defiance of convention, and didn't think twice about a nude swim in the Pemi, 50 yards from the town's cars and pedestrians.

We waded out into the middle of the Pemi streambed leaving our clothes on a wide, flat rock: blue jeans, a pair of clogs, shorts and t-shirts, a wallet stuffed in an old running shoe, a watch tucked into a buttoned pocket.. .and then we drifted downstream in the current, feeling our way with our feet in front of us, moving through the darkness in a loose group held together by occasional talk just loud enough to be heard over the gentle rushing of water around us, absorbed by the water's coolness. We were young, and it was summer, and we drifted in the moment, vaguely aware of its beauty but not caring or thinking about how it would end.

Eventually, the moment passed. We waded and swam for a while, then headed back upstream to where we had left our clothes. When we got there, we were surprised by a man also naked pulling our things out of the water. "She threw your clothes in," he said.

"Who is SHE?" "Who are YOU?" raced to my mind but didn't come out. An ear-splitting blast shattered the night air. We snapped toward the sound and the river bank. The outline of a white shirt moved closer. A girl. "Don't nobody move or I'll shoot!"

The man stepped away from us, as if to distract her. He took two steps toward her and another blast exploded. Shouts of pain shot through the darkness. The girl, not ten feet in front of us, still had a gun in her hand. I yelled, "YOU GUYS GET DOWN!"

Viva and I bolted for the cover of a boulder. Jim, Ingeborg, and Barb still not believing gunshots had been fired stayed on the rock. Viva and I scrambled from the boulder and took off through the woods for the nearest lighted building. I knew we had to get an ambulance to the scene, and it occurred to me that we might be surrounded by poison ivy and broken bottles, but here I was running buck naked through a thicket, having just seen a man take a bullet, and all I could say, over and over, was "MY GOD OH MY GOD OH MY GOD."

The nearest lighted building was Truant's Taverne. I left Viva in the shadows and headed to it. I grabbed a Ski 93 tourism tabloid and covered my privates and started in. Unbelievably, the bar stools were mostly filled. A large man at the bar saw my outfit and ran out from behind the beer taps to intercept me. He had no intention of letting me in.

"You gotta call an ambulance!" I blurted. "A guy just got shot down at the river!" My earnest and sober aspect must have outweighed my nakedness he turned and headed straight to the wall phone. As soon as the ambulance was on the way. he escorted me quickly to his car and found me a pair of shorts.

"Where is Viva?" I high-tailed it up to our car, and there she was, wearing a button-down shirt that looked like an oversized smock. An ambulance siren wailed. Then Jim, Ingeborg, and Barb appeared out of the night wearing and carrying drenched clothes. Everyone was all right, but none of us could stop talking. The police showed up and wanted us for immediate questioning. They allowed that, yes, it would be okay if we first retrieved our clothes from the Wash Works Laundromat.

The questioning extended interminably into the morning hours. The police worked up theories that "our" women must have aroused the girl's jealousy, and proffered questions like, "Just what were you doing with that fellow down there?" "Did you actually see a gun?" I learned that Jim, thinking he'd been a victim of an elaborate gag, had remained on the rocks and chided the locals for putting on such a show just to scare us. Barb had stood there naked while the guy was writhing in pain, and said things like, "Are you really hurt?" while memories of firstaid courses went through her brain, and while Ingeborg calmly insisted, "Barb, get your clothes on; let's get out of here!" Viva, leaving me to go into Truant's, had stood in the shadows, politely asking some local high school kid if she could borrow his shirt. He was the same misdirected youth, as it turned out, who earlier in the evening had pestered us from shady corners, asking, "Are you cool? Hey, are you cool?" We left with the warning that we'd be hearing about a court date later that summer.

The next morning we stumbled into breakfast, and another crew member absolutely refused to believe that the shooting had occurred. He was sure we had spent the evening in Truant's concocting the whole story. Only later that morning, as we sorted through our wet clothes and found the victim's pants and wallet mixed in with our own stuff, was he convinced that it had actually happened.

The hearing came in August. When we got out of the car outside the hearing room, we exchanged friendly glances with the rehabilitated though limping man. (He was 26 years old, wed learned, a victim of the wrath of the teenage girl's unrequited love; he had taken a .45 slug in the hip.) One by one, in a small hearing room, we told our stories. I stared straight ahead and nervously answered the questions; I don't even recall seeing the girl. After Barb spoke, the lawyer for the defense pointed out that although we all quoted the girl as saying, "Don't nobody move or I'll shoot!" like some line out of a bad Western none of us had put that in our police report, intimating that we'd made the line up in our many retellings of the story.

To be sure, the story was well-worn by us all, and it pervaded our collective mythology of the summer. On the way back to the Ravine Lodge from the hearing, we joked about the whole ludicrous affair, but the jokes were wearing thin, and in a few weeks we were back in Hanover, absorbed in the fall term's classes. I don't even-remember when I learned that the accused, still a minor, was simply placed on probation.

NONE OF US EVEN FOUND out exactly what transpired that night. I did go back once, to see if I could learn any more about the unanswered questions. I paced the area where the main action of that night took place. Nearly 12 years of water had washed over the rock since that night. Standing on it then, on an April morning with the Franconia Range's melting snow pack gathering into a torrent of standing waves in the gentle pool where we swam, it was hard to reconcile the present with my history of the place. The blood and tears of the moment had been churned down through the rapids and over the seven dams of the Pemigewasset and Merrimack Rivers, through idle flatwater and canyons walled by brick factories at Manchester and Lowell, their particles long since mingled with sea water in Plum Island Sound and the Atlantic Current.

I visited with the chief of police, who had questioned us in 1981. In a neat office in the town's new municipal building, he leaned back in his chair and dredged up a few memories of the incident. The records from the case are sealed, he told me. "The accused was a minor at the time of the shooting. The trial papers will never be released in her lifetime." He also told me that the victim and the girl had married three years after the shooting, but the relationship was a rough one and they had eventually parted ways.

I stopped pushing. What pains had caused the girl to shoot the man never seemed to interest any of us, and though the cautious questions I asked around town yielded names and a few facts about where I might find the two people, it just didn't seem like my business.

What strikes me now, looking back on the whole affair, is that the terror of the moment struck a spiritual chord in me. In the terror of that moonless, humid night, it was the Lord's name and not a thoughtless profanity that came repeatedly from the hps of a heretofore agnostic 20-year-old. You could say I got religion then, only I'm not sure it stuck.

It has taken more than ten years for me to attach even that significance to what went on that night. At the time, we simply laughed at the event, noted that we were lucky not to have caught a stray slug, and went on to the next adventure, perhaps thinking that if this could happen during a laundry run, much wilder things must be in store for us in the future.

But wilder things have not happened. And so we find ourselves telling and retelling the story of The Pemi Affair. I haven't seen Ingeborg or Barb since I graduated, but this year when I mentioned to one of the students I coach that I'd once witnessed a shooting, he replied that someone named Ingeborg had told the story to the Hanover High Nordic ski team. ("The guy was killed, right?" he said.) The story must have spread to a few campuses beyond Hanover, as well, because a Putney School skier came up to me at a race once and asked, "Hey, aren't you the guy that got shot at Dartmouth?"

Grinning, I asked, "Do you want the short version of the story or the long one?"

one of us ever found out exactly what transpired that night.

ou could say I got religion then, only I'm not sure it stuck.

Kirk Siegei is director of public affairs at Gould Academy in Bethel, Maine, where he also coaches cross-countryand biathlon ski teams. He worked at the Moosilauke Ravine Lodge during summers between 1979 and 1983.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

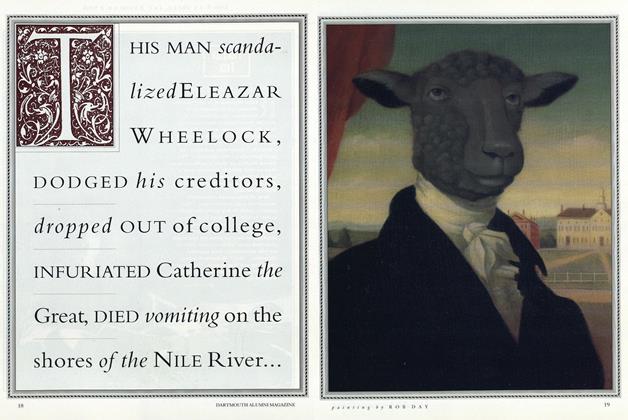

Cover StoryThis Man Scanndalized Eleazar Wheelock

June 1993 By Jerold Wikoff -

Feature

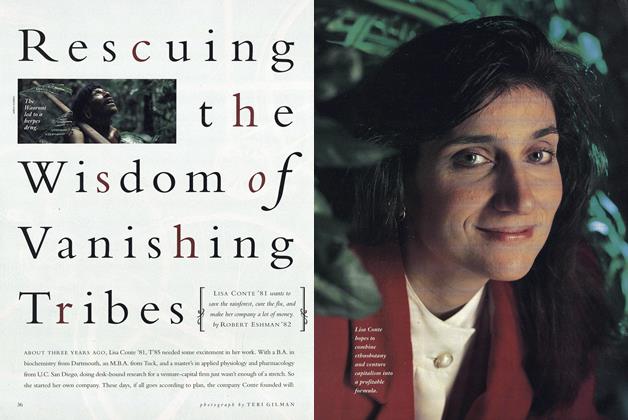

FeatureRescuing the Wisdom of Vanishing Tribes

June 1993 By Robert Eshman '82 -

Feature

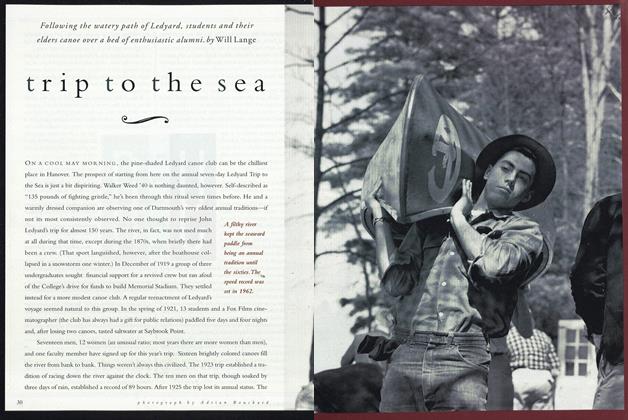

FeatureTrip to the sea

June 1993 By Will Lange -

Feature

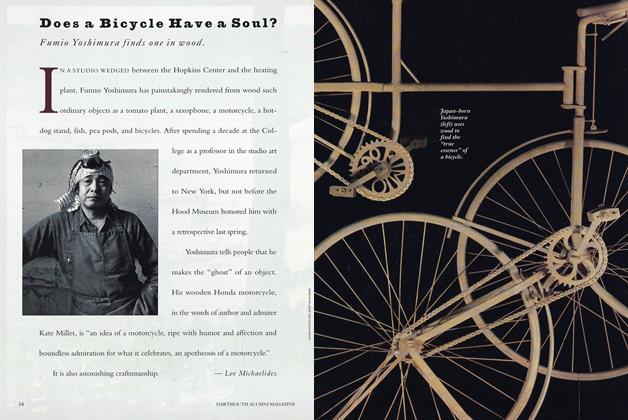

FeatureDoes a Bicycle Have a Soul?

June 1993 By Lee Michaelides -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

June 1993 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

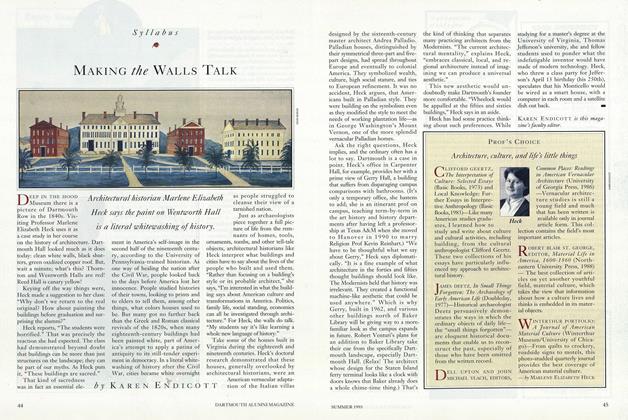

ArticleMaking the Walls Talk

June 1993 By Karen Endicott

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO RAISE HAPPY KIDS

Jan/Feb 2009 By CHRISTINE CARTER '94 -

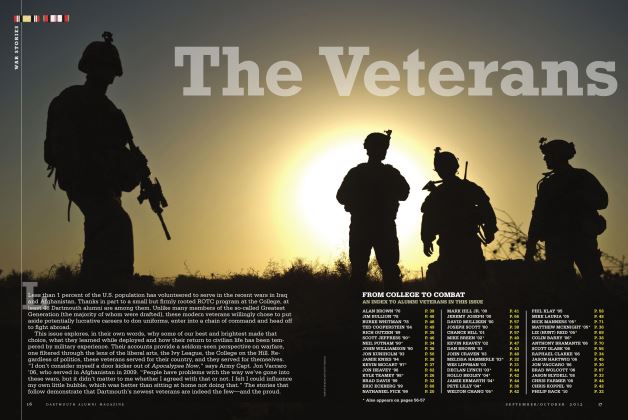

FEATURE

FEATUREThe Veterans

Sep - Oct By COMPILED BY LISA FURLONG -

Feature

FeatureMovie Producer

DECEMBER 1969 By HAROLD BRAMAN '21 -

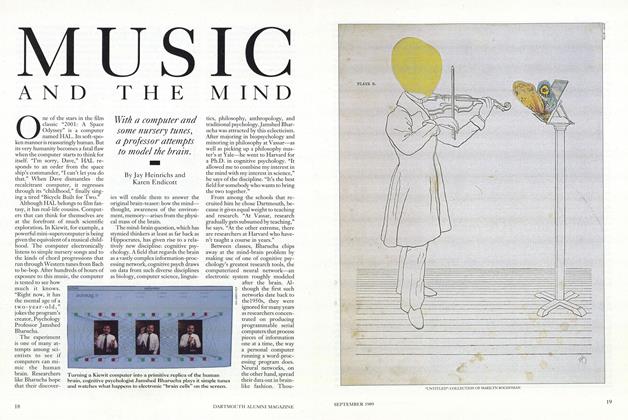

Cover Story

Cover StoryMUSIC AND THE MIND

SEPTEMBER 1989 By Jay Heinrichs and Karen Endicott -

Feature

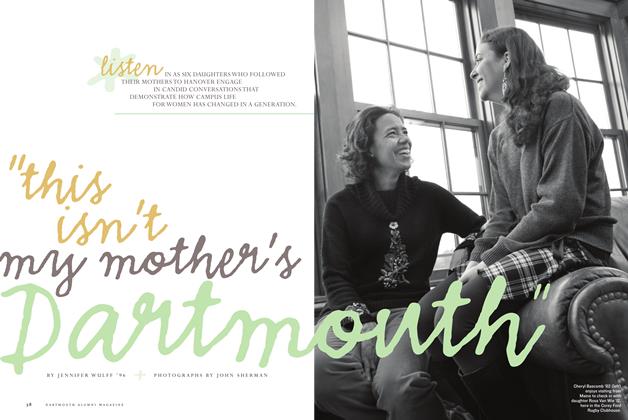

Feature“This isn’t My Mother’s Dartmouth”

Sept/Oct 2010 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

FeatureWhen They Resisted

May 1979 By Steven E. Tozer