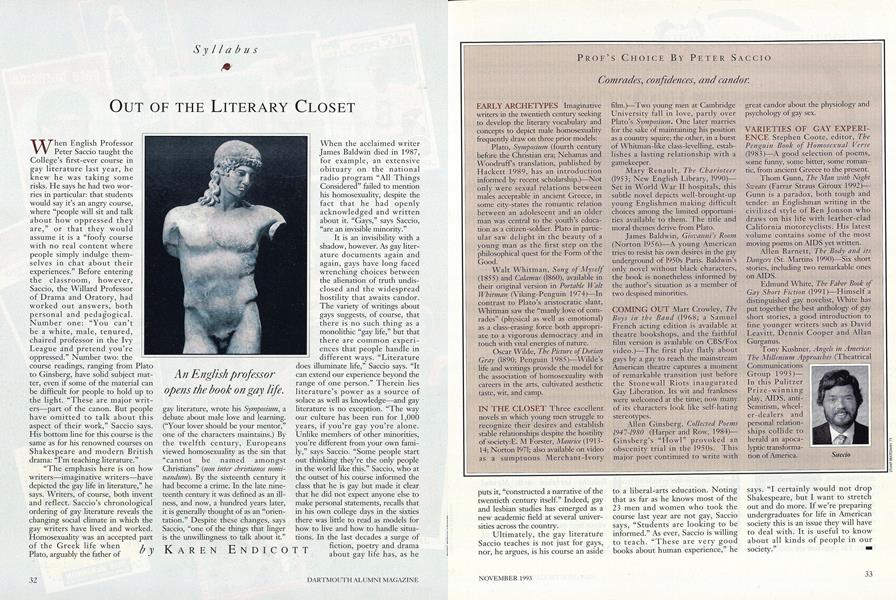

When English Professor Peter Saccio taught the College's first-ever course in gay literature last year, he knew he was taking some risks. He says he had two worries in particular: that students would say it's an angry course, where "people will sit and talk about how oppressed they are," or that they would assume it is a "foofy course with no real content where people simply indulge themselves in chat about their experiences." Before entering the classroom, however, Saccio, the Willard Professor of Drama and Oratory, had worked out answers, both personal and pedagogical. Number one: "You can't be a white, male, tenured, chaired professor in the Ivy League and pretend you're oppressed." Number two: the course readings, ranging from Plato to Ginsberg, have solid subject matter, even if some of the material can be difficult for people to hold up to the light. "These are major writers—part of the canon. But people have omitted to talk about this aspect of their work," Saccio says. His bottom line for this course is the same as for his renowned courses on Shakespeare and modern British drama: "I'm teaching literature."

"The emphasis here is on how writers imaginative writers have depicted the gay life in literature," he says. Writers, of course, both invent and reflect. Saccio's chronological ordering of gay literature reveals the changing social climate in which the gay writers have lived and worked. Homosexuality was an accepted part of the Greek life when Plato, arguably the father of gay literature, wrote his Symposium, a debate about male love and learning. ("Your lover should be your mentor," one of the characters maintains.) By the twelfth century, Europeans viewed homosexuality as the sin that "cannot be named amongst Christians" (non inter christianos nominandum). By the sixteenth century it had become a crime. In the late nineteenth century it was defined as an illness, and now, a hundred years later, it is generally thought of as an "orientation." Despite these changes, says Saccio, "one of the things that linger is the unwillingness to talk about it." When the acclaimed writer James Baldwin died in 1987, for example, an extensive obituary on the national radio program "All Things Considered" failed to mention his homosexuality, despite the fact that he had openly acknowledged and written about it. "Gays," says Saccio, "are an invisible minority."

It is an invisibility with a shadow, however. As gay literature documents again and again, gays have long faced wrenching choices between the alienation of truth undisclosed and the widespread hostility that awaits candor. The variety of writings about gays suggests, of course, that there is no such thing as a monolithic "gay life," but that there are common experiences that people handle in different ways. "Literature does illuminate life," Saccio says. "It can extend our experience beyond the range of one person." Therein lies literature's power as a source of solace as well as knowledge and gay literature is no exception. "The way our culture has been run for 1,000 years, if you're gay you're alone. Unlike members of other minorities, you're different from your own family," says Saccio. "Some people start out thinking they're the only people in the world like this." Saccio, who at the outset of his course informed the class that he is gay but made it clear that he did not expect anyone else to make personal statements, recalls that in his own college days in the sixties there was little to read as models for how to live and how to handle situations. In the last decades a surge of fiction, poetry and drama about gay life has, as he puts it, "constructed a narrative of the twentieth century itself." Indeed, gay and lesbian studies has emerged as a new academic field at several universities across the country.

Ultimately, the gay literature Saccio teaches is not just for gays, nor, he argues, is his course an aside to a liberal-arts education. Noting that as far as he knows most of the 23 men and women who took the course last year are not gay, Saccio says, "Students are looking to be informed." As ever, Saccio is willing to teach. "These are very good books about human experience," he says. "I certainly would not drop Shakespeare, but I want to stretch out and do more. If we're preparing undergraduates for life in American society this is an issue they will have to deal with. It is useful to know about all kinds of people in our society."

An English professoropens the book on gay life.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

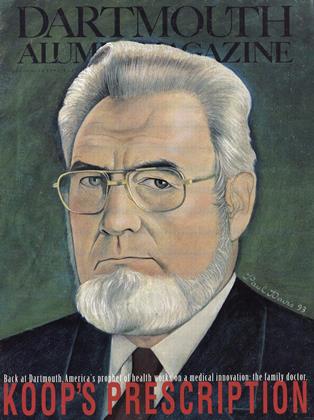

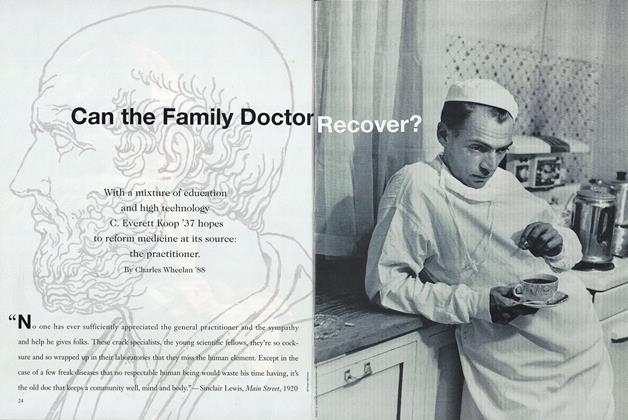

Cover StoryCan the Family Doctor Recover?

November 1993 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

FeatureTHE OLD MEN AND KC

November 1993 By Brooks Clark '78 -

Feature

FeatureProphet of Limits

November 1993 By Suzanne Spencer '93 -

Feature

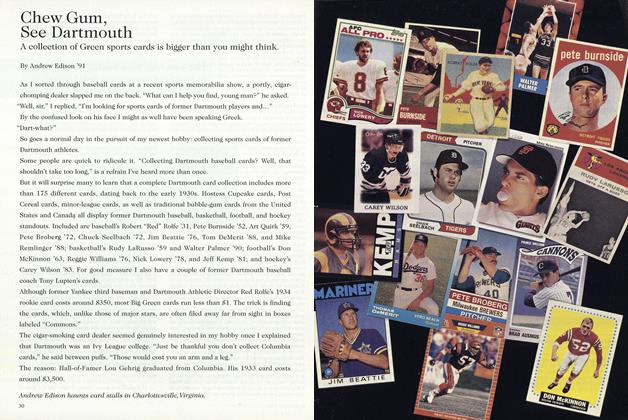

FeatureChew Gum, See Dartmouth

November 1993 By Andrew Edison '91 -

Article

ArticleDivers Notes & Observations

November 1993 By "E. Wheelock" -

Class Notes

Class Notes1975

November 1993 By William Blake, W. Blake Winchell

Karen Endicott

-

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

June • 1988 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH AUTHORS

OCTOBER 1988 By Karen Endicott -

Article

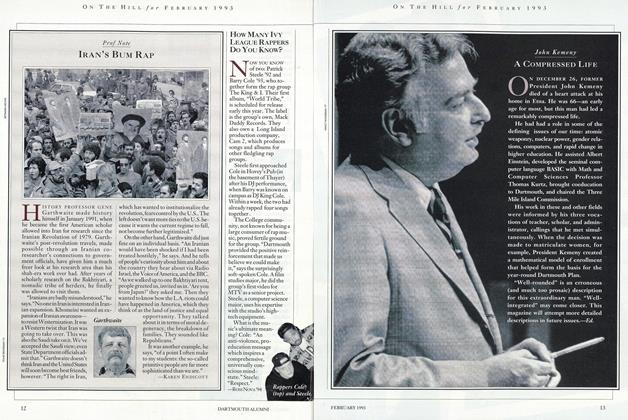

ArticleIran's Bum Rap

February 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleThe Daughters of Eve

October 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleDaedalus with a Power Glove

OCTOBER 1994 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleJapan's Ambivalent Story

OCTOBER 1988 By Mary Scott, Karen Endicott