There’s a small gulf between what Dartmouth’s environmentalists preach and what the College practices.

ENVIRONMENTALLY SPEAKING, DARTMOUTH is one of the best colleges in this country. It has a huge recycling program—and that program expands every few months. One of the latest additions is a collection box for batteries all over campus. Another is a system called “Rough Draft,” which collects computer paper that has been used on only one side and uses it on the other. We have a new and ambitious composting program for food wastes from Thayer Dining Hall. A brand-new College truck, powered by propane, does most of the collecting.

And recycling isn’t the half of it. The engineers at Buildings & Grounds (now called Facilities Operations and Management) are busy installing compact fluorescent lights as fast as they can get them. There’s a program to encourage the use of stairs instead of the College’s 25 ele- vators. Best of all, the environmental education of fresh- men now begins even before they arrive on campus.

Glance up at the epigraph. It’s quoted from a mailing sent to about-to-be members of the class of ’97 last sum- mer. It invited them to buy what’s called the “The Reusable Package.” In it: a mug they can use for four years (and get bargain refills at Thayer); a set of stainless steel cutlery to use first on their freshman trips and later in the Courtyard Cafe and Collis, instead of throw-away plastic; and a big green-and-white bandanna. Cost: a mere $7.25. A quarter of tire class did order die package. Is it any wonder that the EPA recently gave the College an award for having the best waste-reduction program of any institution of higher learning in New England?

And yet...best program in New England doesn’t say much. Most of the others are piddling. And waste reduc- tion is by no means all there is to environmentalism. In fact, the College’s behavior is a great puzzle. I hasten to add that a similar puzzle lurks at any college or univer- sity where environmental studies is taught.

The puzzle is this: How come what Dartmouth does is so pitifully small compared to what environmental-studies faculty think needs to be done? How can events like last year’s Environmental Summit in Rio come and go, and leave so many College policies unchanged? Most environmental teachers in this country believe that we are approaching a crisis. For humanity and for most other animal species, that is; not for the planet itself, which will go serenely on. There are several scenarios, some more alarming, some less. One predicts the crash of human pop- ulation back down to a billion. When? Next century. If it occurs, colleges and universities will crash, too. Words like “endowment” will be quaint relics from the past. Phrases like “appreciated securities” probably won’t even exist.

The crisis is approaching because people in the industrial nations use too much energy, release too many pollutants, drive too many cars, and so on. The time during which we can change our behavior and avert major trouble is short. “We have 20 to 30 years left in which to avert a probable collapse of our industrial civilization,” says Professor Donella Meadows, probably the best-known of Dartmouth’s environmentalists. “We must either cut resource-use per individual, or control population growth, and probably we must do both,” says Professor Ross Virginia, chair of the program.

But cutting resource use is not what most colleges are doing. Let me look in some detail at the actions of Dartmouth, the place I know best and care about most. Study those actions, and it is clear that neither the Trustees nor the administration really believe there is a coming crisis.

Take the matter of energy. What is this “too much” that Americans use? Well, last year John Holdren, professor of energy at Berkeley, came to Dartmouth to give a speech on that very subject. Americans, said Professor Holdren, consume 11 kilowatts per person, continuously. To use the traditional metaphor, that’s the same as if each of us kept a hundred and ten 100-watt light bulbs turned on permanently. What we’re actually doing, of course, is running refrigerators (spectacularly inefficient ones, which consume three or four times the energy they need to—the small ones in student rooms are super-wasters), driving cars, supporting the Air Force, buying energy- intensive aluminum pans, playing in speedboats.

The United States could run, Professor Holdren said, on about three kilowatts per person. It could do so without giving up our plush way of living, just by being efficient. The alternative, he said, is to go on using 11 kilowatts apiece—and to edge closer to the crisis.

That’s the theory. Now let’s look at the practice. Is the number-one waste reducer in New England also conserv- ing energy? No. At one time it did. But right now the College is spending energy like a drunken sailor.

Fifteen or 20 years ago, in the aftermath of the Arab oil embargo, the College really did reform. It insulated build- ings, installed low-flow showerheads, put in sophisticated heating controls. It did even more basic things, like clos- ing holes. In those days I was chairman of the English Department, and I participated in one hole-closing myself. An engineer from B&G and I checked the dozen or so fireplaces in Sanborn House and found that most of them had no dampers. Every winter since the building went up in 1929, they had been pouring streams of heated air into the icy New Hampshire sky. Energy was cheap; who cared? Now B&G installed dampers.

All these efforts paid off. Dartmouth’s use of electricity, which had been climbing steadily for three-quarters of a century, reached a peak in 1977. Then it began to drop. In two years it dropped from 24.6 million kilowatt hours down to 22.5 million. Hardly the two-thirds cut Professor Holdren says we need, but a good start. «l.l< t 1 • 1

The good start then fizzled miserably. In 1980, electrical use at Dartmouth resumed its climb. Most years it has gone up by a million kilowatt hours or more. The figure now stands at 35.4 million.

How can this happen even as the compact fluorescent lights go in? Simple. Like the rest of America, the College is on an appliance binge. The College library alone uses three-quarters of a million kilowatt hours annually, most- ly for appliances. Until quite recendy it was a place where people manually handled books.

But the most striking case is students and their comput- ers. The College now requires every student to own a computer, and it encourages them to buy printers. (Fifty percent of last year’s freshmen did buy printers.)

For their part, many students leave computers turned on, whether they’re using them or not. It’s good for the hard drive, and also handy in case an e-mail message comes in. Figure 80 watts all day and often all night for a couple of thousand student computers. You get half a million kilo- watt hours right there. Throw in more moderate use of several thousand more computers. Add Kiewit’s own 1.6 million kilowatt hours, and you’ve got quite a figure.

As to printers, many students buy a Style Writer that draws only 20 watts—and many get a personal laser print- er that draws 600. There is no doubt that a laser printer does better graphics. There is also no doubt that it uses more energy. To increase the chance of collapsing our civilization so that undergraduates can put fancy title pages on their papers seems a curious choice.

Am I suggesting that students should not have comput- ers? Of course not. I’m suggesting they could have them at a small fraction of the present energy cost if they would just turn them off when not in use. The same is true for TV sets, by the way. At present 99 percent of American TV sets draw energy continuously, whether the screen is bright or not.

Forget about energy for a minute, and think about College vehicles. Dartmouth owns about 40 trucks and vans. One of them, of course, is that splendid new propane-powered truck. The other 39 are all guzzlers. Half the trucks belong to Facilities Management, and half of that half travel only five to ten miles a day, in short hops. This is the kind of driving during which gasoline vehicles pollute tire most.

But as any environmental teacher knows, vehicles that travel only five to ten miles a day are ideal for converting to electric. Then you’d have a zero-emission fleet.

Zero? Well, almost. The vehicles themselves emit noth- ing. The power plants that supply their electricity do; this is called upstream pollution. But guess what. There’s upstream pollution for gasoline cars, too—oil drilling, refining, tanker crashes, etc. In some parts of the United States, these amounts of pollution are the same. Says who? Says Professor Andrew Ford of the University of Southern California (and Ph.D. from Dartmouth), making a study of die impact the first million electric cars will have in south- ern California. Because of coal-fired power plants, the two figures are not the same in New Hampshire, but the gain in cleaner air per electric vehicle is still vast.

Electric vehicles are currentiy more expensive than guz- zlers, and that is presumably why Dartmouth doesn’t have any. There is no cash payback.

You do not have to think only in those terms. You could think instead like the German government, which consid- ers environmental payback, too. Example: Germany is about to exempt electric vehicles from use taxes for a peri- od of five years. A drop in revenue, but an increase in sur- vivability. The state of Arizona had similar thoughts two years ago, when it decided to institute a two-tier registra- tion fee for passenger cars. Fee for a new $20,000 gasoline car; $490. Fee for an electric car costing the same: $17.50. A drop in revenue, but a big gain in air quality. The town of Hanover had similar thoughts last summer when it decided to get an electric truck for the police department. (Chief Kurt schimke is already dreaming of an electric cruiser.) As I write, it looks as if the Thayer school is also going to get an electric pickup. But not the College.

If the College were to think like Arizona or Germany, a lot of things would change. One is the rate at which com- pact fluorescent lights go in. I said Facilities Management was installing them as fast as it can get them. That’s not stricdy true. It’s installing them as fast as it can get them with money provided by Granite State Electric. When the annual grant is spent, work ceases until next year. I also said the College is an outstanding recycler. It is, but only for half the cycle. “We encourage recycling, because we save money by it, but we don’t buy many recycled prod- ucts,” says Bill Hochstin, manager of General Plant Housekeeping and director of Dartmouth Recycles.

I see only two plausible explanations for the gulf between what Dartmouth’s environmentalists preach and what dre College practices. One is that the Trustees simply do not believe that there is any such danger looming as their environmentalists assert, that we are wrong. In that case, shouldn’t they be troubled by the alarming things we tell students, the misinformation we spread? Shouldn’t they get rid of as many of us as possible, and then hire a staff who will teach what is true?

That’s one possibility. Not, I think, the likely one. Because if they think we are wrong, they simultaneously have to think the National Academy of Sciences is wrong. Also the Royal Society, over in London. In 1992 those august bodies issued the first joint statement they have ever made. It concerned the environment. “The future of our planet is in the balance,” said all those top scientists. If industrial countries don’t make major changes, they con- tinued, expect “irreversible damage to the earth’s capacity to sustain life.” Strong words. Why are they so hard to hear on the Green?

The likely answer is that the Trustees—and the adminis- tration and our fellow faculty—do believe most of what environmentalists have to say, but only on a conscious level, not yet a gut level. I think they are a little like the British in 1941. Everyone in England knew that Japan had entered the war, but they didn’t really believe that Singapore was going to fall, and Rangoon, and every British outpost, or that the Japanese could sink their bat- tleships like bathtub toys.

I am devoted to the College, where I have worked for 34 years. I am proud of the recycling program. Proud of the Trustees for having recently so far seen the light as to extend the payback period for conservation measures from five years to eight. Proud of the engineers at Facilities Management. Clear that we rank a full grade ahead of most academic institutions, in or out of New England. Most deserve a C- at best, and to many I would give a D. It is precisely because I’m so fond of the College that it saddens me to see the powers that be acting as if the future of Dartmouth and of the nation were secure. They’re not, and at our present 11-kilowatt-per-person way of living, they won’t be. ™

Phantom Loads

TV sets are not the only appliances that stay on fulltime. A lot of electronic appliances draw what is called a phantom load. (It is perfectly real, however, down at the power plant.)

Portable telephones, for example, draw a constant 12 watts, 24 hours a day. When the little battery is fully charged, electricity continues to dribble into the phone—and then gets dissipated as waste heat. Gives your air conditioner something to do in the summer.

TV sets themselves draw between 20 and 30 watts when they are “off.” Answering machines draw ten to 12 watts just sitting there, neither answering nor recording. And according to an EPA report, the typical computer draws 30 watts when it is off.

If this is so, then most Dartmouth computers are not typical. The Macintosh SE and Classic, the models owned by most students, draw no power at all when fully switched off. Score several points for Dartmouth.—Noel Perrin

EPIGRAPH: Dartmouth College #1 in Ivy Football #1 in Women’s Ice Hockey #1 in EITA Men’s Tennis #1 in RECYCLING —Outing Club letter, 1993

A crisis is approaching because people in the industrial nations use too much energy and release too many pollutants.

Each American continuously uses the equivalent of a hundred and ten 100-watt light bulbs turned on permanently.

Noel Perrin, who joined the faculty in 1959, formerly taught Americanliterature and now teaches environmental studies. For the past threeyears he has commuted to work in his electric car. (It's a 21-mile roundtrip.) Last summer he began to mow his lawn with a battery-poweredelectric riding latmmower. He hopes to be cutting firewood next fallwith an electric chainsaw. (David Cramer '93, Thayer '94 will bedesigning the circuitry. This was arranged by engineering ProfessorUrsula Gibson 'l6, once Perrin's student in a science fiction course.)

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryProcrastinator’s Night Confessions of a Collegiate Insomniac

Winter 1993 By Jane Hodges ’92 -

Feature

FeatureBIG JUMP

Winter 1993 By David Bradley ’38 -

Feature

FeatureMoriarty Ad Lib

Winter 1993 By Robert Sullivan ’75 -

Article

ArticleDivers Notes & Observations

Winter 1993 By “E. Wheelock” -

Article

ArticleThe City Peter Built

Winter 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleA Lifelong Pursuit of Education

Winter 1993 By James O. Freedman

Noel Perrin

-

Books

BooksTHE CHRISTENING PARTY.

February 1961 By NOEL PERRIN -

Feature

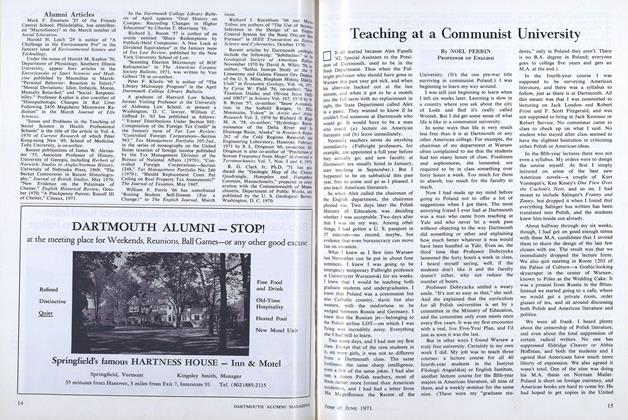

FeatureTeaching at a Communist University

JUNE 1971 By NOEL PERRIN -

Books

BooksUrban Romantics

April 1976 By NOEL PERRIN -

Article

ArticleDo Good Computers Make Good Writers?

APRIL 1997 By Noel Perrin -

Curmudgeon

CurmudgeonThe Problem with the Dorm-Room Fridge

NOVEMBER 1999 By Noel Perrin -

CURMUDGEON

CURMUDGEONBring Back the Vox!

Sept/Oct 2000 By Noel Perrin

Features

-

Feature

FeatureMiraculously Builded

NOVEMBER 1999 By David M. Shribman ’76 -

Feature

FeatureFifty-Five Out

September 1993 By Judson D. Hale '55 -

Feature

FeatureEgyptologist

DECEMBER 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

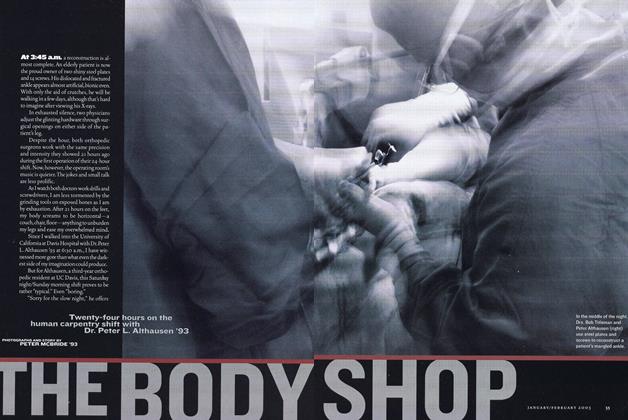

FeatureThe Body Shop

Jan/Feb 2003 By PETER MCBRIDE ’93 -

Feature

FeatureThe Mystery of the Tao

NOVEMBER 1998 By Rebecca Bailey -

Feature

Feature1958 ALUMNI FUND REPORT

DECEMBER 1958 By William G. Morton '28