After graduating in 1992 I moved to a small apartment in Hyde Park, Chicago. I was told that a man living upstairs had been a faculty member at Dartmouth in 1932.1 did not have enough courage to introduce myself, until he spotted me in a school sweatshirt more than a year later and invited me up to talk.

The rest, literally, was history.

Dale Pontius was an assistant in the government department for one year, 1932-33. Prohibition was lifted when he was there. Students and professors celebrated during their annual outing trip in May by lugging bottles of beer up Mt. Lafayette. Dale showed me pictures in an old album of the Lost River and the mountain they climbed that weekend, and of a crowd at the summit, raising their bottles to the camera.

On campus Dale often saw Jose Orozco resting his eyes in the movie theater after worrying over his murals all day. Dale introduced himself one evening, and the two had a few drinks at a town pub. Dale described him as an intense, exuberant man who thought studio painting was "women's work."

There were rumors of an impending international crisis stirring up the town that winter. A professor returning from a leave of absence in Germany had brought a small, disturbing book back with him Mein Kampf It was the first time anyone in Hanover had seen a copy. Dale met with other faculty to discuss its significance. "I remember thinking it was very dark that night, as I walked back to my room a dark night in the middle of the winter."

One of his lasting impressions of Dartmouth was the blizzard of 1933. A storm came in the middle of May that year, dropping 30 inches of snow on Hanover, cutting power lines, and severing the campus from the outside world. "Do they still talk about it?" he asked me. I told him I'd seen pictures of students walking on planks across the Green, or diving out of their dorm windows into snow banks, or just standing there, frozen or contented. To be honest, I never bothered to look at the year.

It was a Depression year, a year of competing ideologies. Dale met once a week with a dozen students interested in the way the town was run. At his suggestion they began to interview people during their spare time to determine Hanover's economic power structure. It seems that some did not appreciate Dale's civic-mindedness; President Hopkins was among them. Though the government department had promised Dale a contract extension at the end of the year, it did not come through.

Like all conversations, ours drifted from one subject to another. Dale stopped to fetch some apple cider from the refrigerator, as I recalled one of my last days in Hanover. To one side of Mass Row there is a small Korean mountain ash, which bears fruit in the fall and flowers each spring. The day before my graduation a few friends gathered with my family and dedicated it to my father, Allan Wall '68. It could not be fully dedicated. I had no personal memories of my father to relate that day. He died when I was very young.

As a child I was told that my father often sat at the top of Bartlett Tower and wrote poetry. The first time I visited campus I climbed the tower steps and searched for his initials beneath the roof. But there were too many scraped on those wood beams, and too much time had passed to know for sure if he, in a bored moment, had carved out a few letters.

For some the past is a thing that presses against them. Students hear alumni condemn the present College, preferring, perhaps, a Dartmouth they attended long ago a place many of us could not or would not have considered home for four years. But even as students struggle against the words of the alma mater, or the claypipe ceremony, or, sometimes, against the very history of the College, they pass into it.

I have come to believe this: that there are different times, and they all exist together. If we open to them by gathering around small trees, or by talking to strangers in a new city, then these lost voices will pass into us. I know of no other way to develop a true living sense of place.

We do not make history. We listen to it, in odd afternoons, with a glass of apple cider. It reminds us that we do not inhabit this place alone.

We are possessed, and lifted up, by such stories. CHRISTOPHER WALL '92 mysteries and the hard science behind reindeer flight. The photographically illustrated article, which is in the magazine's "How Things Work" department, quotes eyewitnesses who have visited Santa Claus's training camp on the ice cap near the North Pole, others who have been visited by Claus, meterologists who have helped Claus plan his Christmas Eve itinerary, and finally a career U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service biologist who has spent decades studying reindeer and Santa Claus receives from many and diverse governments worldwide. "No single sack is big enough for Claus's cargo, so he shutdes back to the Pole all night long," Young told Life. He added that airlines restrict flights over the pole to avoid accidents.

The author of the piece, Robert Sullivan '75, contacted Young in October saying he had been tipped off to the facts of flying reindeer while doing a story years ago in far northern Canada.

"That made some sense to me," Young says. &

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

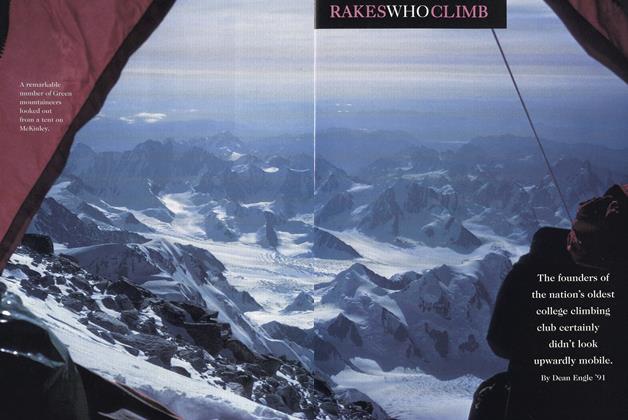

FeatureRAKES WHO CLIMB

February 1994 By Deab Engle '91 -

Feature

FeatureTau Iota Tau and Other Brassy Memories

February 1994 By Regina Barreca '79 -

Cover Story

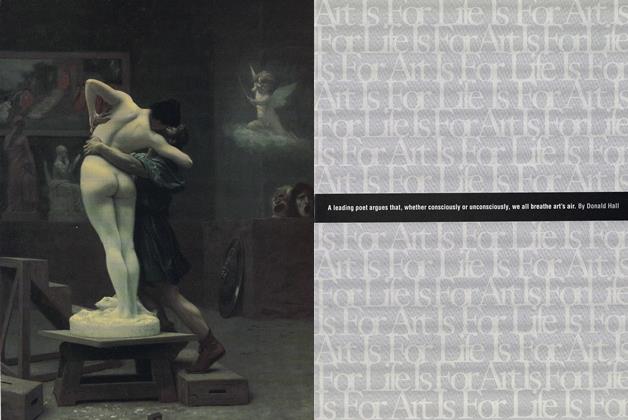

Cover StoryA leading poet argues that, whether consciously or unconsciously, we all breathe art's air.

February 1994 By Donald Hall -

Feature

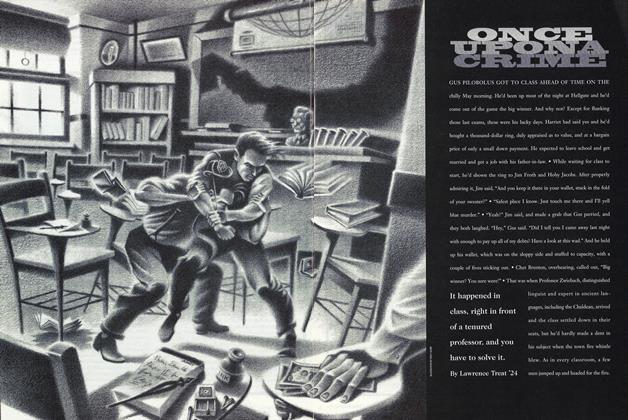

FeatureONCE UPON A CRIME

February 1994 By Lawrence Treat '24 -

Feature

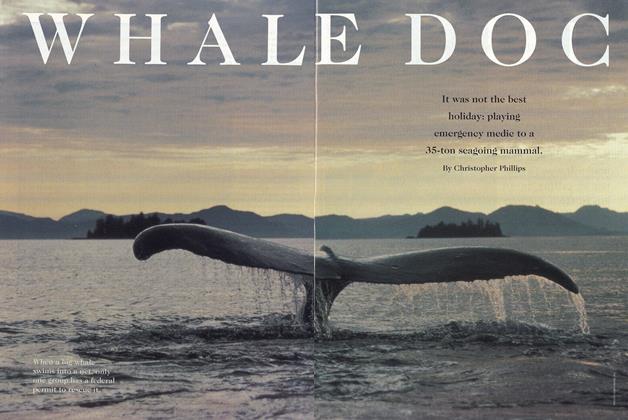

FeatureWHALE DOG

February 1994 By Christopher Phillips -

Article

ArticleDr. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

February 1994 By "E. Wheelock"

Article

-

Article

ArticleDEGREES TO GRADUATES OF THAYER AND TUCK SCHOOLS

July 1920 -

Article

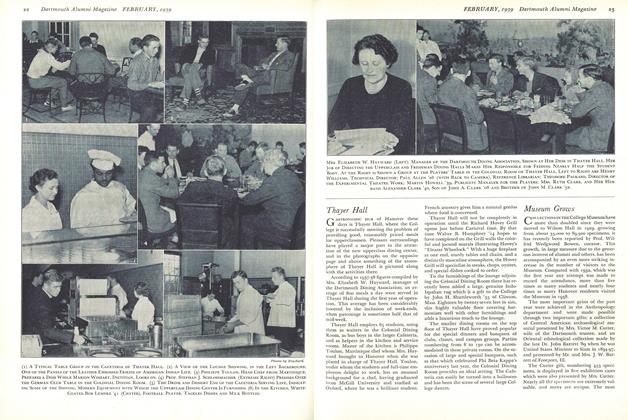

ArticleMuseum Grows

February 1939 -

Article

ArticlePhi Beta Kappa

April 1948 -

Article

ArticleFootball Film Ready

January 1952 -

Article

ArticleOnce Upon a Time

NOVEMBER 1996 By Heather Killebrew '89 -

Article

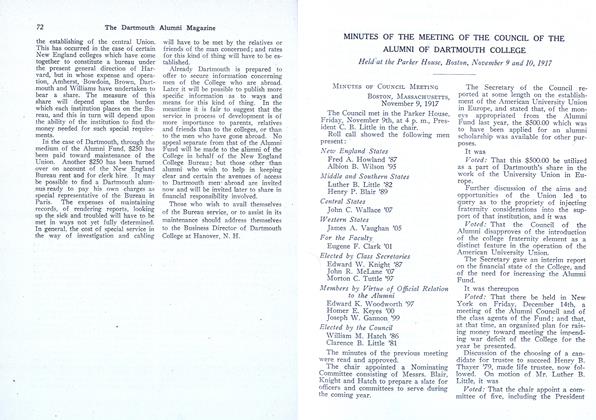

ArticleMINUTES OF THE MEETING OF THE COUNCIL OF THE ALUMNI OF DARTMOUTH COLLEGE

December 1917 By HOMER EATON KEYES