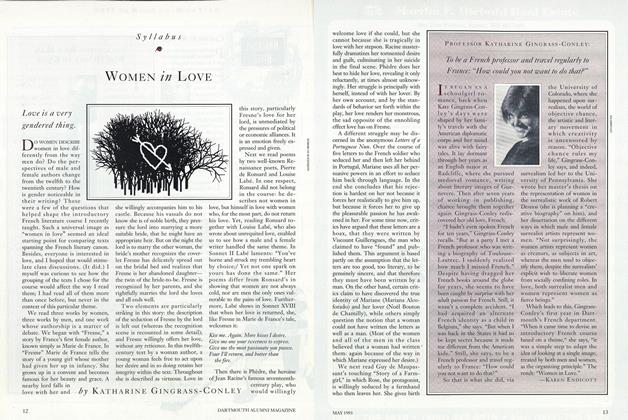

To be a French professor and travel regularly toFrance: "How could you not want to do that?"

IT BEGAN AS A schoolgirl romance, back when Kate Gingrass-Conley's days were shaped by her family's travels with the American diplomatic corps and her mind was alive with fairy tales. It lay dormant through her years as an English major at Radcliffe, where she pursued medieval romance, writing about literary images of Guenevere. Then after seven years of working in publishing, chance brought them together again: Gingrass-Conlev redis- covered her old love, French.

"I hadn't even spoken French for ten years," Gingrass-Conlev recalls. "But at a party I met a French professor who was writing a biography of Toulouse-Lautrec. I suddenly realized how much I missed French." Despite having dragged her French books around the globe for years, she seems to have been caught by surprise with her adult passion for French. Still, it wasn't a complete accident. "I had acquired an alternate French identity as a child in Belgium," she says. "But when I was back in the States it had to be kept secret because it made me different from the American kids." Still, she says, to be a French professor and travel regularly to France: "How could you not want to do that?"

So that is what she did, via the University of Colorado, where she happened upon surrealism, the world of objective chance, the artistic and literary movement in which creativity is uncensored by reason. "Objective chance rules my life," Gingrass-Conley says, and indeed, surrealism led her to the University of Pennsylvania. She wrote her master's thesis on the representation of women in the surrealistic work of Robert Dcsnos (she is planning a "cre- ative biography" on him), and her dissertation on the different ways in which male and female Surrealist artists represent wo- men. "Not surprisingly, the women artists represent women as creators, as subjects in art, whereas the men tend to objec- tify them, despite the surrealists' explicit wish to liberate women from socially confining roles. In love, both surrealist men and women represent Women as fierce beings."

Which leads to this, Gingrass- Conley's first year in Dartmouth's French department. "When it came rime to devise an introductory French course based on a theme," she says, "it was a simple step to adapt the idea of looking at a single image, treated by both men and women, as the organizing principle." The result: "Women in Love."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

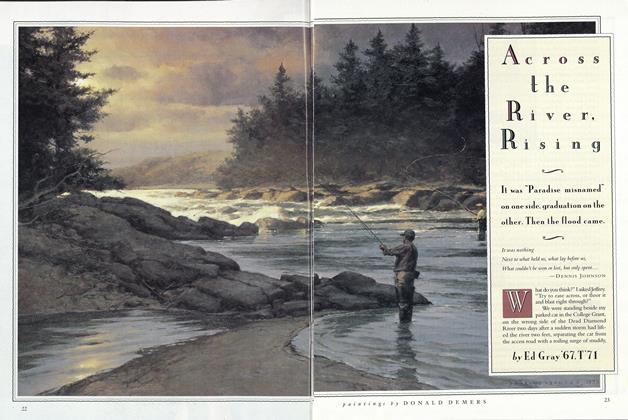

FeatureAcross the River, Rising

May 1993 By Ed Gray '67, T '71 -

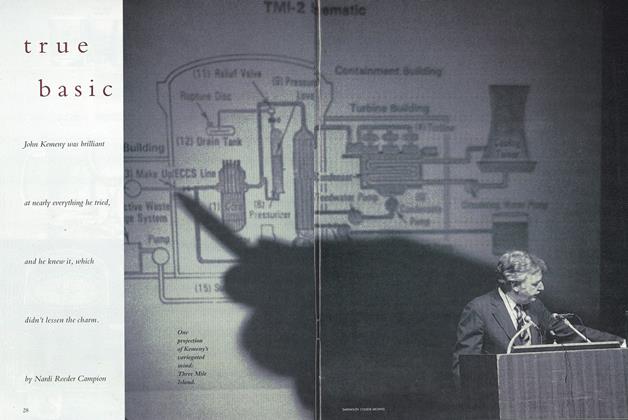

Cover Story

Cover StoryTrue Basic

May 1993 By Nardi Reeder Campion -

Feature

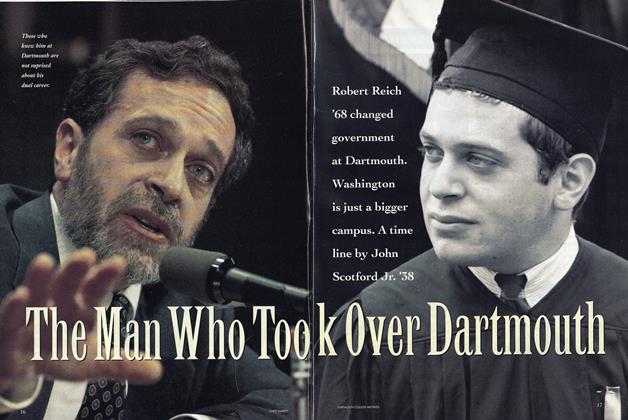

FeatureThe Man Who Took Over Dartmouth

May 1993 By John Scotford Jr. '38 -

Article

ArticleWomen in Love

May 1993 By Katharine Gingrass-Conley -

Article

ArticleA Postponed Power

May 1993 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

May 1993 By E. Wheelock

Karen Endicott

-

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

June • 1988 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleGaudeamus Igitur!

September 1993 By karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleCuring Fake Patients

OCTOBER 1994 By Karen Endicott -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMCode of Life, Codes of Conduct

Sept/Oct 2000 By Karen Endicott -

Article

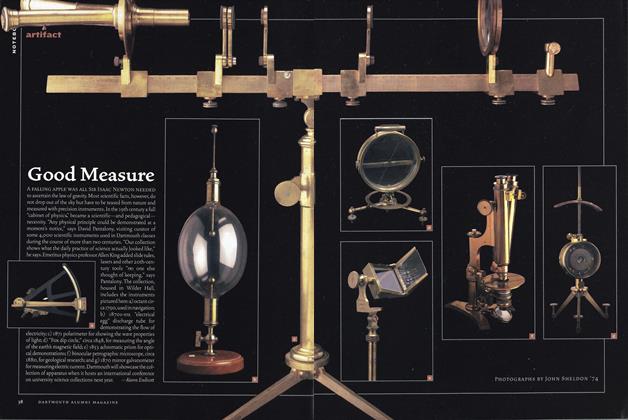

ArticleGood Measure

Sept/Oct 2003 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleCOMPUTING AND THE RING OF INVISIBILITY

JUNE 1991 By Professor James Moor, Karen Endicott

Article

-

Article

ArticleSOUTHERN CALIFORNIA ASSOCIATION

JANUARY, 1927 -

Article

ArticleCOLLEGE REPRESENTED AT ACADEMIC FUNCTIONS

AUGUST, 1927 -

Article

ArticleMedical School

January 1947 -

Article

ArticleMay Schedules

May 1950 -

Article

ArticleWHY DARTMOUTH?

February, 1923 By E. GORDON BILL -

Article

ArticleLARGE NUMBER WORKING WAY

June 1938 By Ralph N. Hill '39