Anyone who has tossed at night while a song plays on in the recesses of the mind knows that music and words are a powerful combo, hard to turn off and hard to resist. Advertisers, of course, rely on this phenomenon. And, working in the loftier realm of artistic expression, writers and composers have long scaled the heights of emotion by combining words with music.

Surprisingly, given this emotive power and the sheer number of songs, operas, and other music that fill human existence, there are few academics who study the intersection of music and literature. One of them is German Professor Steven Paul Scher, who teaches a comparative-literature course entitled "Literature and Music," and publishes extensively in that field (see, for example, his "Literature and Music" in the Modern Language Association publication Interrelations ofLiterature). There are, of course, plenty of professors and critics who specialize in either music or literature. It is far rarer, Scher explains, for academics to be competent enough in both fields to straddle the boundaries that usually separate the musical from the literary.

Scher came up through both ranks, his Hungarian youth a mix of music studies and reading. He says it was records and books smuggled in from the West including Aldous Huxley's BraveNew World that saw him through what he calls "the darkest Stalinist years." He had started at the music conservatory in Budapest; in the wake of the failed uprising of 1956 he fled to Vienna and took up German. A Stanford professor of Hungarian descent visiting at the University of Vienna recommended Scher to Yale, which admitted him as a sophomore. "I didn't know enough English at first so I gravitated to German literature," he says. Call it accident, call it fate. German is the language of scores of the world's finest composers and writers.

To aid discussion of music and literature, Scher divides the field into three major areas. The first, music and literature, covers the various forms of vocal music notably choral music, opera, and lieder (art songs), in which texts are set to music. By the middle of the eighteenth century, opera was considered the highest art form, and musicians increasingly turned to composing it and related forms of texted music. Ironically, however, in opera it is the music rather than the text that grabs most people.

"Music goes more directly to you than literature," explains Scher. But text is not merely lip-service to the music. Says Scher, "Vocal music has been regarded as a primarily musical genre. No one would seriously think of, say, Verdi's operas based on Shakespeare's plays or Schubert's Goethe lieder as first and foremost literary creations. Yet interpreters of such works cannot dispense with the literary aspect of the relation. Just as librettos without music rarely succeed as plays, Mozart's best operas wouldn't be what they are without the brilliance of Da Ponte's librettos."

Then there is what Scher calls literature in music, music that doesn't have a text but is inspired by literature. Franz Liszt, for example, wrote what he called "symphonic poems," wordless musical equivalents of poetry, such as his composition Hamlet. The rich repertoire of music inspired by literature—including Debussy's Prelude to the Afternoon ofa Faun, based on a poem by Mallarme is the legacy of composers singing the highest praise a musician can offer a literary work: bringing it to life musically.

The flip side is what Scher calls music in literature, where it is the writers who pay homage to music by embedding it even imitating it in literary works. Huxley, for example, consciously structured his novel Point Counter Point along musical lines. Thomas Mann's novel DoctorFaustus contains a central passage, Scher says, that is "a veritable 'verbal score' of the Prelude to Act III of Wagner's opera Die Meistersingervon Nurnberg." Some writers even verbally compose fictitious music, like the violin sonata Marcel Proust imagined into his seven-part novel Remembrance of Things Past. Early in the first part, Swarm's Way, the main characters attend a soiree at which the sonata is played. "The music gets into their heads and resurfaces throughout the later volumes," Scher explains. So effective are some fictitious pieces of music that musicians have tried to compose music modeled on them a kind of music imitating literature imitating music.

Scher theorizes that "a composer as reader would bring a different kind of competence to a text than an ordinary reader," though he adds that "a great deal of violence can be done to the text." His ultimate question is this: "Can there be a perfect fusion between the two arts?" He has answers. One is Mozart's and Da Ponte's opera Don Giovanni. The other is Schumann's lied Mondnacht (Moonlit Night), "a simple, transparent poem by Eichendorff in a beautiful setting." ™

Like lovers entwined, music and literaturesing each others praises.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

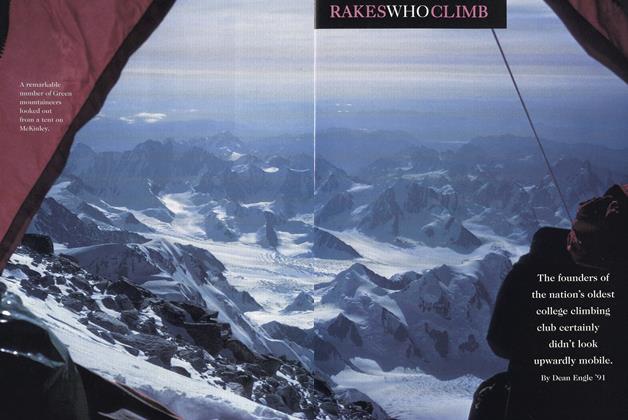

FeatureRAKES WHO CLIMB

February 1994 By Deab Engle '91 -

Feature

FeatureTau Iota Tau and Other Brassy Memories

February 1994 By Regina Barreca '79 -

Cover Story

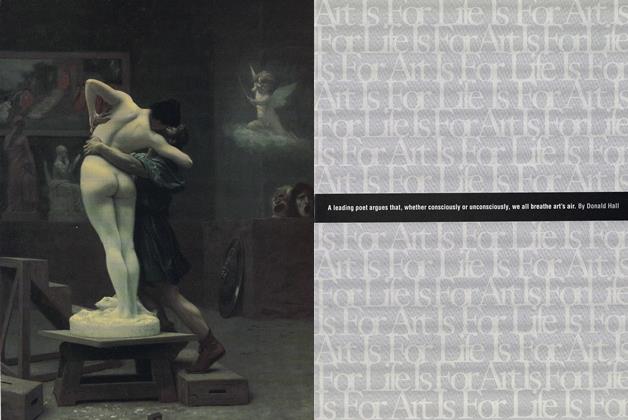

Cover StoryA leading poet argues that, whether consciously or unconsciously, we all breathe art's air.

February 1994 By Donald Hall -

Feature

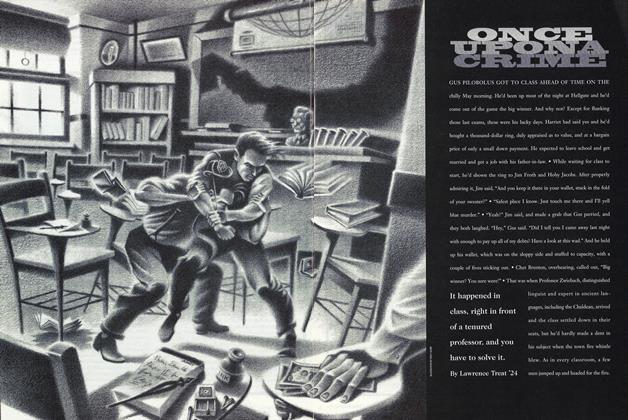

FeatureONCE UPON A CRIME

February 1994 By Lawrence Treat '24 -

Feature

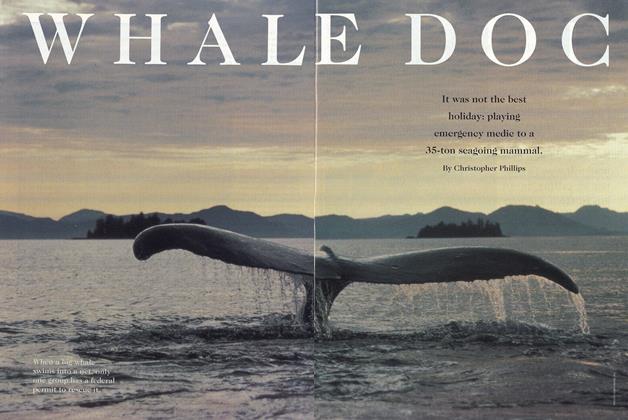

FeatureWHALE DOG

February 1994 By Christopher Phillips -

Article

ArticleDr. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

February 1994 By "E. Wheelock"

Karen Endicott

-

Article

ArticleA Hero in American Education

NOVEMBER 1989 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleReligion Professor Hans H. Penner

MAY 1992 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleEducation By A Man Who Ought to Know

May 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleFilling The Power Vacuum

June 1994 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleWHAT the ELDERS WROTE

October 1995 By Karen Endicott -

Classroom

ClassroomIs There a Robot In the House?

Nov/Dec 2001 By KAREN ENDICOTT

Article

-

Article

ArticlePresident Nichols, the alumni bring you greeting and farewell.

June 1916 -

Article

ArticlePRESIDENT LOWELL'S RESIGNATION

January 1933 -

Article

ArticleSpring Term in Greece

DECEMBER 1967 -

Article

ArticleSharpless Reaction

APRIL 1994 -

Article

ArticleDivers Notes & Observations

December 1992 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleGIFT OF ART

APRIL 1965 By R.B.