When Russ Mittermeier '71 first proposed his senior fellowship topic, "Ecology, Behavior, and Conservation of New World Monkeys," which required field work deep in the jungles of Panama, his professors weren't too keen. "They thought I was nuts. They thought I'd go off into the jungle and get eaten by something. It was not until I actually wrote them from there [Panama] and showed them that I had not been eaten that they finally gave me the fellowship."

Now Mittermeier, who has survived countless jungle expeditions and become a world renowned expert on "ecosystem preservation," is president of Conservation International, a three-year-old non-profit organization devoted to saving endangered wilderness and animals.

Ecosystem preservation means working with the humans whose use of a given area jeopardizes wildlife, forests, and other natural resources. Mittermeier, who earned a Ph.D. in anthropology from Harvard shortly after leaving Dartmouth, is recognized worldwide as one of the most effective workers for this cause.

"Apart from being a world academic leader [in the study of primates in their natural habitats], he is very pragmatic," observes Robert Goodland, the World Bank's chief ecologist. Goodland, who has known Mittermeier for seven years, worked with him in a recent effort to save thousands of square kilometers of Brazilian forest. Goodland notes that though his colleague is "one of the world's leading authorities" on primates and their habitats, "he's not just a researcher. He wants to protect the organisms he studies."

Mittermeier joined Conservation International last June and has raised more than $8 million, nearly double the organization's previous pace. One of his most effective fundraising techniques is taking donors along on academic expeditions in the jungle, into the thick of the problems their money will help to solve.

He came from ten years at the World Wildlife Fund, most recently as vice president for sci- ence, working under its former head, Environmental Protection Agency Administrator William Reilly. Mittermeier's approach to conservation typically identifies endangered species and gives them a voice, through lectures, publications, films, and other media, and through sponsorship and encouragement of other researchers—all of which contributes to a heightened public awareness of the problem he targets. Among many successful initiatives, Mittermeier helped put the muriqui monkey, one of the two most endangered primate genera in the Western hemisphere (only a few hundred remain), on a Brazilian stamp, placing the deep-jungle mammal and its plight within the daily ken of the country whose efforts will determine the primate's survival.

He recently appeared on the Today show, discussing Cl's current initiative, The Rain Forest Imperative. This program identifies areas whose preservation is key to what Mittermeier calls the earth's "megadiversity." There are 15 targeted spots—Madagascar, the Philippine archipelago, and the eastern Himalayan foothill, to name three—all of which cover just .2 percent of the earth's land surface but contain 12 to 20 percent of its plant species and countless animal species. Under Mittermeier, CI will help coordinate conservation efforts with the people inhabiting these areas.

If Mittermeier's work takes him all over the world, so did his work at Dartmouth. He was attracted to the College, in part, by its off-campus opportunities, and spent much of his college career on foreign soil.

"I'm not a cold weather person," Mittermeier says. "I was only there taking courses six out of 12 terms."

The rest of the time? He spent two terms on Foreign Study Programs, in France and Germany, working on two of the languages in which he is fluent (Spanish and Portuguese are others). Then there was that senior fellowship in Panama, which resulted in a 300-page discussion of his research and several published articles.

Mittermeier, who majored in anthropology, says that department "gave me the opportunity to basically design my own program . . . studying a great variety of topics." Now, as president of Conservation International, Mittermeier will continue to set his own course, while setting the agenda for some of the world's most important conservation efforts.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

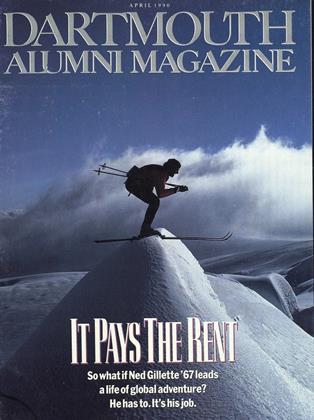

Cover Story

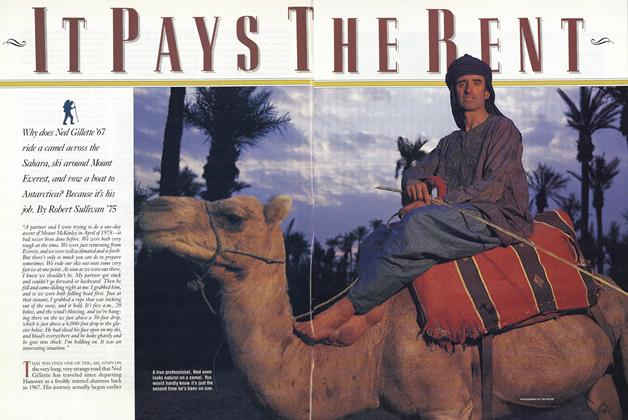

Cover StoryIt Pays The Rent

April 1990 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

FeatureTaking God's Word For It

April 1990 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleA Few Of Dartmouth's Adventure Pros

April 1990 By Jim Collins '84, Andrew 's mother, Ed -

Article

ArticleOn chemistry, Cuba, and other radical elments on the campus.

April 1990 -

Article

ArticleThe Satanic Verses: Why Were Muslims So Offended?

April 1990 By A. Kevin Reinhart -

Article

ArticleA SENSE OF PLACE

April 1990 By Professor Jere Daniell '55, Joni B. Cole

Timothy J. Burger '88

-

Article

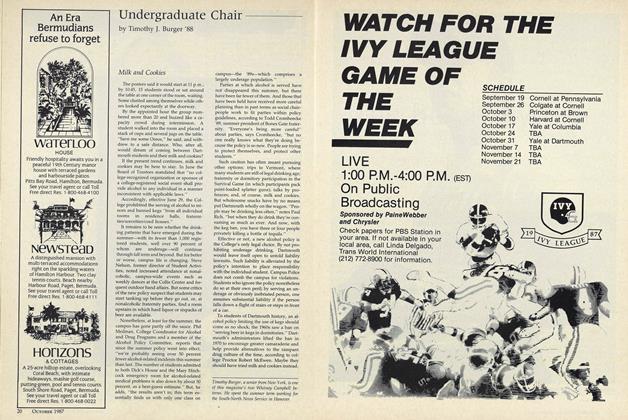

ArticleMilk and Cookies

OCTOBER • 1987 By Timothy J. Burger '88 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryIf I Could Do It Over

December 1987 By Timothy J. Burger '88 -

Article

ArticleA Sun-Powered Race Between Two Very Different Schools

December 1988 By Timothy J. Burger '88 -

Article

ArticlePolitics by Design

NOVEMBER 1990 By Timothy J. Burger '88 -

Feature

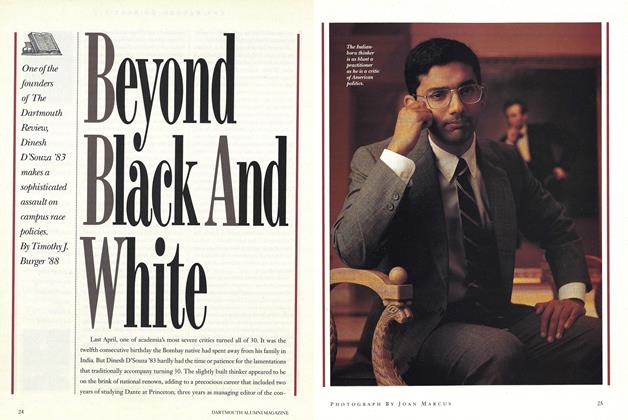

FeatureBeyond Black And White

JUNE 1991 By Timothy J. Burger '88 -

Cover Story

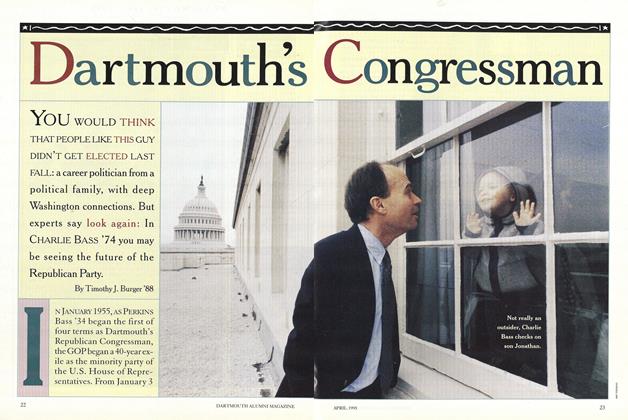

Cover StoryDartmouth's Congressman

April 1995 By Timothy J. Burger '88

Article

-

Article

ArticleTHANKSGIVING DAY

-

Article

ArticleTHAYER SCHOOL REACHES 50TH ANNIVERSARY OF ITS FOUNDING

June 1921 -

Article

ArticleFootball Ticket Survey

APRIL 1932 -

Article

ArticlePresident's Assistant.

MARCH 1967 -

Article

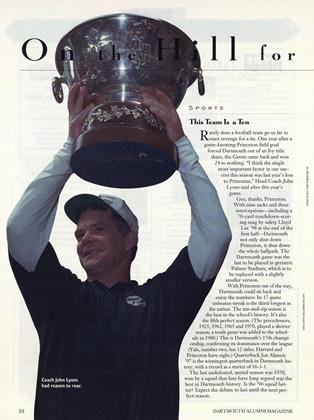

ArticleThis Team Is a Ten

JANUARY 1997 -

Article

ArticleA Hard Job of Education A Hard Job of Education

June 1946 By JOHN W. FINCH