Why the Play’s Still the Thing

The purpose of plays, wrote Shakespeare, is to hold a mirror up to nature. An English class peers into his looking glass.

May/June 2001 Karen EndicottThe purpose of plays, wrote Shakespeare, is to hold a mirror up to nature. An English class peers into his looking glass.

May/June 2001 Karen EndicottThe purpose of plays, wrote Shakespeare, is to hold a mirror up to nature. An English class peers into his looking glass.

"DON'T CALL HIM'THE bard.' It makes me puke," English professor Peter Saccio informs his Shakespeare class. (He isn't being uncouth, he's being literary. Shakespeare was the first writer to use the word "puke," in As You LikeIt, Act II, scene 5, line 144.) If you must use a synonym for Shakespeare, Saccio tells the class, "call him 'the playwright' or 'the dramatist' or the poet.' "

Saccio doesn't care that the term "Bard of Stratford" has been around since the 19th century. It's inaccurate, he explains. Bards were early Greek and Celtic poets who composed verse that was sung or chanted. Shakespeare "wrote plays for a sophisticated theater in a sophisticated culture," Saccio says.

Four centuries later, Shakespeare remains the most quoted playwright of all time. "For generations people have looked to Shakespeare to tell us about ourselves," says Saccio in class. "All generations re-interpret him, but they go back to him."

No wonder more than 100 students choose Saccio's annual course each time he teaches it. As he leads them through 10 plays (one a week) from four genrescomedy, history, tragedy and romance-Saccio transforms lectern into stage, breaking into dramatic readings to bring Shakespeare's words alive. Though Saccio does almost all the talking, he expects students to play their own active role. "I get responses from your faces," he tells them. "If you know the plays, you'll be much more responsive."

Saccio begins by acclimating students to Shakespeare's 16th-century vocabulary. And there's a lot of it. Shakepeare used 30,000 different words. The Bible, by contrast, contains only 10,000 distinct words. "Shakespeare knew more words than God," Saccio tells students. But don't be intimidated, he adds. "To overlook the quality of words in Shakespeare is like looking at a sculpture without noticing if it is made of marble or bronze," he says.

To ease students into the language and meter of Shakespeare's work, Saccio recommends that they listen to audiotapes while reading the plays. He also makes videotapes available to them. And this term Saccio starts students off with a play that is built on meter, A Midsummer Night's Dream. In this comedy about the irrationality of love, Saccio explains, five plot lines employ different ways of speaking: Royal characters speak in dignified blank verse; workmen rehearsing a play jabber in colloquial prose, then perform in rhymed quatrains; young lovers swept by emotion gush in rhymed couplets; while the uncontrollable, magical world of fairies uses odd and changing patterns of rhyme and meter.

Stepping from behind the lectern, Saccio breaks into an anecdote. While rehearsing actors in A Midsummer Night'sDream, he says, he noticed that every time the word "moon" came up, the meter of the line was thrown off. He recites: "Over hill, over dale/Thorough bush, thorough brier/Over park, over pale/ Thorough flood, thorough fire/I do wander everywhere/Swifter than the moons sphere." He looks at the class. "The moon is out of step," he says. Shakespeare is using meter to make a point, Saccio explains. "The moon is present when strange things happen in this play. The moon literally makes the characters lunatic."

But why did Shakespeare write some, but not all, parts of his plays in verse? Why not just use prose? "Verse commands our attention and heightens the impact of what's being said," Saccio tells the class. "Shakespeare had to get the audience to focus on the speech. This was before stage lighting, which focuses our attention on a character. Shakespeare had some musicians and sound effects, but what he mainly had was actors and lavish costumes. He put the voices of actors to use in verse."

Not that Shakespeare's prose was throw-away. He used it when portraying moments of relaxation or familiarity and when characters are going mad or breaking down, Saccio says. The professor calls the description of the death of Falstaff in Henry V"the most extraordinarily rich emotion in Shakespeare—from bawdy comedy to eternal damnation." Saccio recites the lines in class and explains their nuances, from their deliberately misquoted Biblical references to their mirroring of Plato's description of the death of Socrates. "Shakespeare is a genius—he can write anything!" Saccio exclaims. "He's on the order of Michaelangelo." To underscore his point, Saccio shows slides of the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. "Shakespeare is like this—there is so much there," he says.

Saccio loves this stuff. He has steeped himself in it since age 14. It was then, while reading Richardll, he tells his class, that he came across the lines "let us sit upon the ground/And tell sad stories of the death of kings." That was it. "I fell in love with the power of the words," Saccio says. He's been discussing Shakespeare's stories about kings ever since. In fact, Saccio literally wrote the book on Shakespeare's tales of royalty to separate historical fact from Shakespearean inventions and other fancies. While Shakespeare's history plays draw from the historical texts and cultural understandings of the times, he was writing plays, not schoolbooks. For example, in Richard II, Saccio explains, Shakespeare dramatizes a dilemma arising from the Elizabethan power structure: In a system that supports the divine right of kings, what do you do with a bad king? Shakespeare leads his audiences through the political and personal ramifications of deposing a king—a far more tumultuous event than impeaching a president.

No course on Shakespeare would be complete without covering the tragedy Hamlet. "It's always old and always new," Saccio tells his class. "I have worked on Hamlet for decades but just found a wonderful line I never thought about before."

According to Saccio, Hamlet is an intellectual play, making it a perfect play for college students. Hamlet is a Wittenberg University student who finds himself in what Saccio describes as "appalling circumstances." Hamlet's uncle killed his father, the king, then married his mother. When his fathers ghost orders him to avenge the death, Hamlet doubts the experience. He doubts his mind. Reflecting Elizabethan ideas, he debates whether the ghost is a devil—and therefore to be ignored—or God's messenger—and there- fore to be obeyed. He mines his education to resolve a dilemma that still faces all humans: Why do bad things happen to good people? Along the way he wrestles with competing explanations of evil, contemplates suicide, and ultimately concludes that divine power rules all and that he must accept God's will. "Shakespeare is not preaching ideas to his audience," Saccio tells the class. "He uses ideas in the service of art."

Saccio likes to end his course with Cymbeline. A mix of comedy, love story, history and tragedy, it allows him to use the play as a review of genres, he explains. It's also a play Saccio loves. "It's fantasti- cal and fun," he says. "It's not Shakespeare's best play. It's not a. Hamlet or KingLear. It's a fairy tale. But if I want to read some Shakespeare sitting by my woodstove, I read Cymbeline."

Saccio hopes students will continue their engagement with Shakespeare long after the course is over. "I want students to discover themselves in Shakespeare," he says. "In the long run it isn't we who judge Shakespeare. Because he understands more about the human condition than any of us does, it is he who judges us. He can help us be larger people than we are ourselves."

Ten Weeks, Ten Plays "I want to givestudents their money's worth," saysprofessor Peter Saccio.

COURSE: English 24: Shakespeare I PROFESSOR: Peter Saccio PLACE: 13 Carpenter, three hours per week GRADE BASED ON: Weekly quizzes, one reading exercise, two papers, final exam READING: Shakespeare, edited by David Bevington (Longman); Shakespeare's EnglishKings by Peter Saccio (Oxford University Press)

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

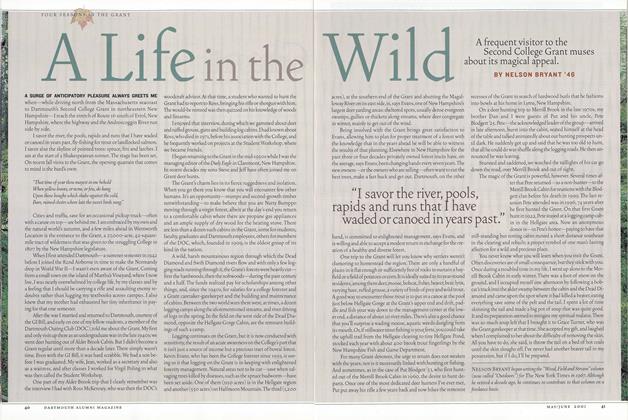

FeatureA Life in the Wild

May | June 2001 By NELSON BRYANT ’46 -

Feature

FeatureShooting the Grant

May | June 2001 By BEN YEOMANS -

Feature

FeatureVoices in the Wilderness

May | June 2001 By Jennifer Kay '01 -

Feature

FeatureTHE GREAT NORTH WOODS

May | June 2001 By Michelle Chin '03 -

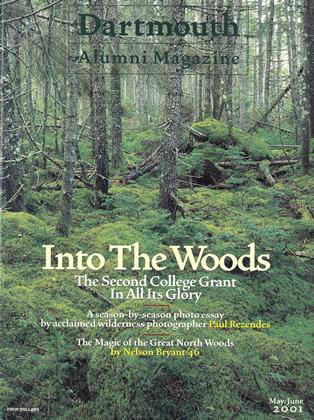

Cover Story

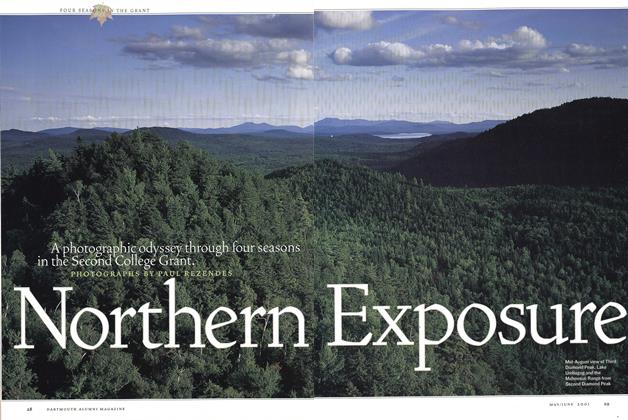

Cover StoryNorthern Exposure

May | June 2001 -

Sports

SportsThe Sporting Life

May | June 2001 By Lily Maclean ’01

Karen Endicott

-

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

MAY • 1988 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH AUTHORS

OCTOBER 1988 By Karen Endicott -

Feature

FeatureTaking God's Word For It

APRIL 1990 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleControlling Self-Control

December 1995 By Karen Endicott -

Classroom

ClassroomIs There a Robot In the House?

Nov/Dec 2001 By KAREN ENDICOTT -

Article

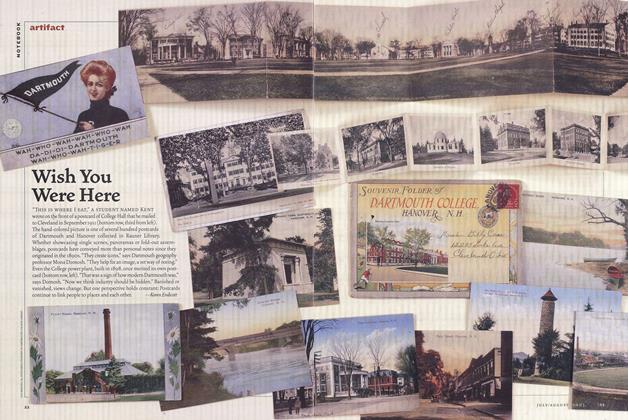

ArticleWish You Were Here

July/Aug 2003 By Karen Endicott

Classroom

-

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMHeaven and Hell in the Middle East

July/Aug 2002 By Alex Hanson -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMOptimus Maximus

May/June 2008 By Judith Hertog -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMWarring Factions

Jan/Feb 2009 By Judith Hertog -

CLASSROOM

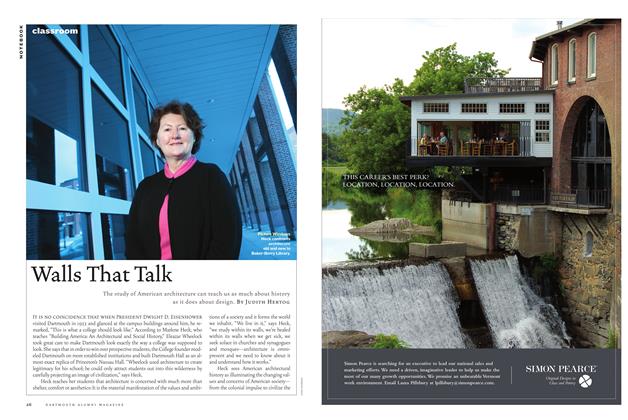

CLASSROOMWalls That Talk

May/June 2009 By Judith Hertog -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMRich Man, Poor Man

Sept/Oct 2011 By Judith Hertog -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMOutside The Box

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2013 By JUDITH HERTOG