IAM ONE of 1,800 work-study students at Dartmouth who earn extra tuition money with a campus job. Unlike my fellow students, however, I do not wash dishes at Thayer or check out library books. Some might call my job dull or even morbid, but I prefer to think of it as just a bit eccentric. I work in the office of the Alumni Magazine, helping to prepare the obituaries.

Each day I delve into yellowed manila folders to find records of promotions, marriages, children's births, retirements, and, finally, deaths. I photocopy newspaper clippings, photographs, and completed alumni surveys and send them to class officers who write the obituaries. ("Necrologists," they call themselves—a word that has become quite familiar of late.) I have been leafing through the files for a few months now, and something odd is happening. The English major in me has taken over. I am no longer merely copying and filing. Instead, I am finding myself in the middle of people's lives.

file I learned what became of this promising young boy: he was a judge who allegedly embezzled millions of dollars before committing suicide.

I read of a 36-year-old alumna who died of a chronic lung disease and left behind a five-year-old daughter. And of a young physician whose small plane crashed in North Dakota as he was paying a regular visit to an Indian reservation. And of a man who had spent the last years of his life as an AIDS activist. And of an aspiring novelist who died of cancer and listed intramural Scrabble on his record of Dartmouth activities.

I find myself choosing between the people I like and the ones I don't. I like the man who lived in Hollywood and launched a surfing store. I like the man who was married to his second wife for only five years before she died and he married a third, but was unashamed to admit to classmates that those second-marriage years were the happiest of his life. I dislike the professor who, before he died, sent in a three-page autobiography describing his theories of Japanese literature and including the titles of every book and article he ever wrote.

Perhaps as a result of these personal reactions, I am also continually surprised when I read the obituaries that are produced from my mounds of photocopied material. Somehow, the unique life stories that I have pieced together from these scraps and clippings are lost. These alumni are reduced to names, dates, occupations, Dartmouth activities, and hobbies. Of course it is nearly impossible to make 200-word obituaries intimate. But I feel as if I know these people, and their obituaries read like little more than headstones.

I am left to wonder what my own file will look like someday. I wonder if some curious Dartmouth student will come across my records. Will she judge me, as I have judged these deceased alumni? Will she flip through the clippings and read about my career as a writer or note that my children did not go to Dartmouth? Will she like me?

I don't know the answers to these questions, and probably never will. I can only hope that when the time comes, my folder is full. Not full of pretentious announcements regarding my career advancements, but full of stories like the ones I've discovered.

Clipping by clipping, we are all silently filling a folder somewhere.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

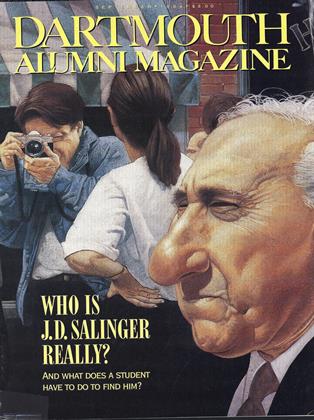

Cover Story

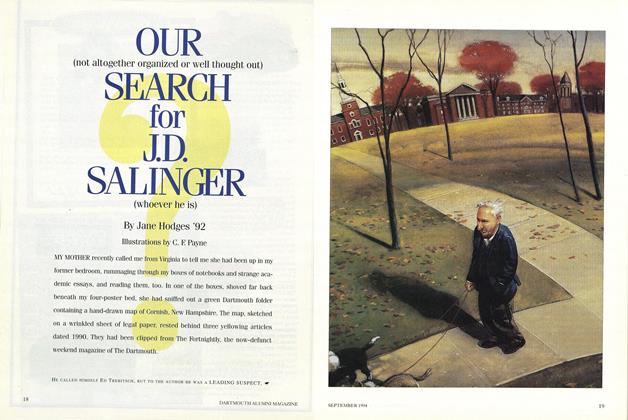

Cover StoryOUR SEARCH FOR J.D. SALINGER

September 1994 By Jane Hodges '92 -

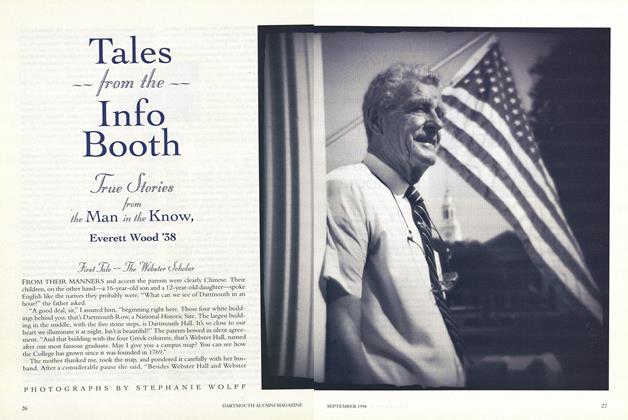

Feature

FeatureTales from the Info Booth

September 1994 -

Feature

FeatureThe Run

September 1994 By Stephen Madden -

Article

ArticleSEX AND THE DEVIL

September 1994 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleWhat the Soul Asks

September 1994 By James O. Freedman -

Class Notes

Class Notes1994

September 1994 By Nihad Farooq

Suzanne Leonard '96

-

Article

ArticleNo Turning Back

September 1995 By Suzanne Leonard '96 -

Article

ArticleDollars and Pounds

October 1995 By Suzanne Leonard '96 -

Article

ArticleThe Female Majority

December 1995 By Suzanne Leonard '96 -

Article

ArticleCONFIDENCE TAKEN CONFIDENCE BUILT

MARCH 1997 By Suzanne Leonard '96 -

Article

ArticleLooking to Dartmouth

JANUARY 1998 By Suzanne Leonard '96 -

Article

ArticleThe Masculine Mystique

MAY 1999 By Suzanne Leonard '96