PLENTY OF ALUMNI HAVE TRANSITIONED FROM THE UPPER VALLEY TO DOT-COM LAND. HERE ARE EIGHT OF THE YOUNGEST—AND MOST INNOVATIVE.

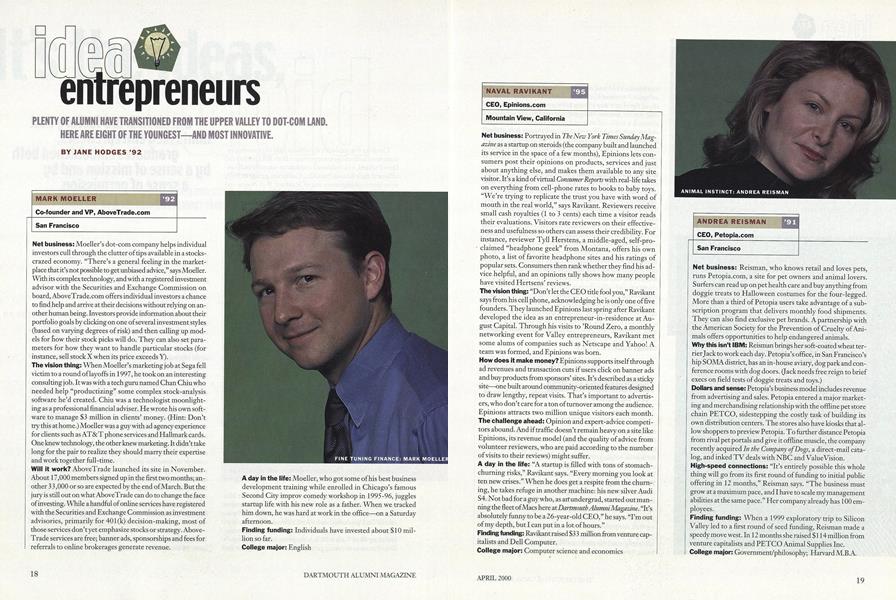

MARK MOELLER '92

Co-founder and VP, AboveTrade.comSan Francisco

Net business: Moeller's dot-com company helps individual investors cull through the clutter of tips available in a stockscrazed economy. "There's a general feeling in the marketplace that it's not possible to get unbiased advice, "says Moeller. With its complex technology, and with a registered investment advisor with the Securities and Exchange Commission on board, AboveTrade.com offers individual investors a chance to find help and arrive at their decisions without relying on another human being. Investors provide information about their portfolio goals by clicking on one of several investment styles (based on varying degrees of risk) and then calling up models for how their stock picks will do. They can also set parameters for how they want to handle particular stocks (for instance, sell stock X when its price exceeds Y).

The vision thing: When Moeller's marketing job at Sega fell victim to a round of layoffs in 1997, he took on an interesting consulting job. It was with a tech guru named Chan Chiu who needed help Productizing some complex stock-analysis software he'd created. chiu was a technologist moonlighting as a professional financial adviser. He wrote his own software to manage $3 million in clients' money. (Hint: Don't try this at home.) Moeller was a guy with ad agency experience for clients such as AT&T phone services and Hallmark cards. One knew technology, the other knew marketing. It didn't take long for the pair to realize they should marry their expertise and work together full-time.

Will it work? Above Trade launched its site in November. About 17,000 members signed up in the first two months; another 33,000 or so are expected by the end of March. But the jury is still out on what Above Trade can do to change the face of investing. While a handful of online services have registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission as investment advisories, primarily for 401(k) decision-making, most of those services don'tyet emphasize stocks or strategy. AboveTrade services are free; banner ads, sponsorships and fees for referrals to online brokerages generate revenue.

A day in the life: Moeller, who got some of his best business development training while enrolled in Chicago's famous Second City improv comedy workshop in 1995-96, juggles startup life with his new role as a father. When we tracked him down, he was hard at work in the office—on a Saturday afternoon.

Finding funding: Individuals have invested about $10 million so far.

College major: English

NAVAL RAVIKANT '95

CEO, Epinions.com Mountain View, California

Net business: Portrayed in The New York Times Sunday Magazine as a startup on steroids (the company built and launched its service in the space of a few months), Epinions lets consumers post their opinions on products, services and just about anything else, and makes them available to any site visitor. It's a kind of virtual Consumer Reports with real-life takes on everything from cell-phone rates to books to baby toys. "We're trying to replicate the trust you have with word of mouth in the real world," says Ravikant. Reviewers receive small cash royalties (1 to 3 cents) each time a visitor reads their evaluations. Visitors rate reviewers on their effectiveness and usefulness so others can assess their credibility. For instance, reviewer Tyll Herstens, a middle-aged, self-proclaimed "headphone geek" from Montana, offers his own photo, a list of favorite headphone sites and his ratings of popular sets. Consumers then rank whether they find his advice helpful, and an opinions tally shows how many people have visited Hertsens' reviews.

The vision thing: "Don't let the CEO title fool you," Ravikant says from his cell phone, acknowledging he is only one of five founders. They launched Epinions last spring after Ravikant developed the idea as an entrepreneur-in-residence at August Capital. Through his visits to 'Round Zero, a monthly networking event for Valley entrepreneurs, Ravikant met some alums of companies such as Netscape and Yahoo! A team was formed, and Epinions was born.

How does it make money? Epinions supports itself through ad revenues and transaction cuts if users click on banner ads and buy products from sponsors' sites. It's described as a sticky- site—one built around community-oriented features designed to draw lengthy, repeat visits. That's important to advertisers, who don't care for a ton of turnover among the audience. Epinions attracts two million unique visitors each month.

The challenge ahead: Opinion and expert-advice competitors abound. And if traffic doesn't remain heavy on a site like Epinions, its revenue model (and the quality of advice from volunteer reviewers, who are paid according to the number of visits to their reviews) might suffer.

A day in the life: "A startup is filled with tons of stomach-churning risks," Ravikant says. "Every morning you look at ten new crises." When he does get a respite from the churning, he takes refuge in another machine: his new silver Audi S4. Not bad for a guy who, as an undergrad, started out manning the fleet of Macs here at Dartmouth Alumni Magazine. "It's absolutely funny to be a 26-year-old CEO," he says. "I'm out of my depth, but I can put in a lot of hours."

Finding funding: Ravikant raised $33 million from venture capitalists and Dell Computer.

College major: Computer science and economics

ANDREA REISMAN '91

CEO, Petopia.comSan Francisco

Net business: Reisman, who knows retail and loves pets, runs Petopia.com, a site for pet owners and animal lovers. Surfers can read up on pet health care and buy anything from doggie treats to Halloween costumes for the four-legged. More than a third of Petopia users take advantage of a subscription program that delivers monthly food shipments. They can also find exclusive pet brands. A partnership with the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty of Animals offers opportunities to help endangered animals.

Why this isn't IBM: Reisman brings her soft-coated wheat terrier Jack to work each day. Petopia's office, in San Francisco's hip SOMA district, has an in-house aviary, dog park and conference rooms with dog doors. (Jack needs free reign to brief execs on field tests of doggie treats and toys.)

Dollars and sense: Petopia's business model includes revenue from advertising and sales. Petopia entered a major marketing and merchandising relationship with the offline pet store chain PETCO, sidestepping the costly task of building its own distribution centers. The stores also have kiosks that allow shoppers to preview Petopia. To farther distance Petopia from rival pet portals and give it offline muscle, the company recently acquired In the Company of Dogs, a direct-mail catalog, and inked TV deals with NBC and Value Vision.

High-speed connections: "It's entirely possible this whole thing will go from its first round of funding to initial public offering in 12 months," Reisman says. "The business must grow at a maximum pace, and I have to scale my management abilities at the same pace." Her company already has 100 employees.

Finding funding: When a 1999 exploratory trip to Silicon Valley led to a first round of seed funding, Reisman made a speedy move west. In 12 months she raised $114 million from venture capitalists and PETCO Animal Supplies Inc.

College major: Government/philosophy; Harvard M.B.A.

DAVID KRAMER '89

Attorney, Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati Palo Alto, California

Net-related business: Kramer has been working for one of the nation's leading high-tech law firms since 1996. Its lawyers work with companies at all stages (from startups to megafirms) on issues such as public offerings and intellectual property rights. One day a partner approached Kramer. "This Internet service provider (ISP) has problems you've never heard of before," he said. Kramer had to figure out those problems and a new framework of legal debate for discussing them. The client had 100,000 subscribers, many of whom were experiencing lots of cyber-intrusions from hackers, connection hijackers and junk e-mailers. The latter problem, known as "spam," became Kramer's overnight specialty, as he set about figuring a way to help ISPs combat high volumes of insignificant, memory-hogging, non-returnable, non-blockable junk e-mail—often from hucksters promoting pyramid andget-rich-quick schemes. After working on several similar cases, Kramer was inspired to write an anti-spam bill that the state of California adopted into law. It is now used as a model in other states and may become the foundation for federal legislation.

Why his work is important: Litigating against spam is critical for any online business. Spammers often swipe an ISP's entire e-mail database, then zap out messages to all subscribers. The thousands of messages sent are an abuse that clogs servers, infringes upon the server-customer relationship and, generally speaking, drives everyone crazy. "The cost of eliminating junk mail, not to mention privacy issues and the lecherousness of your typical spammer schemes, are all problems that result," Kramer explains. By writing a law—based on new interpretations of the concept of criminal trespass—Kramer has helped build the cornerstone of a privacy and safety structure that encourages participation in Internet services.

A day in the life: Kramer wears khakis to work like many Californians and—like many a fellow intellectual property lawyer—spends his days working out copyright infringement lawsuits or sending cease-and-desist "nastygrams," as he calls them. Clients are primarily ISPs, search engines and Internet e-commerce startups. Despite his take on the dark side of e-mail, Kramer nevertheless maintains five accounts. "A few of them," he says, "are spam-free." College major: Economics

ANDREW BEEBE '93

CEO, Bigstep.comSan Francisco

Net business: Beebe's Bigstep offers small businesses an affordable way to create an online presence. While other dotcoms offer similar services, Bigstep stands apart because it focuses on helping small firms establish the complicated ecommerce functions that enable them to sell over the Net. Incredibly, most of Bigstep's services are free. The vision thing: Beebe and some friends, who all worked at companies that built technologies for small business, realized that whenever a client wanted to start selling online, its only option was turning to large, expensive vendors whose solutions went above and beyond the client's needs. "We'd talk to these big tech companies and they'd say things like, 'We're dumbing down our technology for small business,"' says Beebe, who recognized the need for a more reasonable, cheaper solution. In mid-1998 he and his partners started planning their new dot-com business. Beebe says he wants it to become an "America Online for small business." In other words, the place where newcomers can jump easily onto the Web. To do so, Bigstep will have to convince small business owners that its platform is reliable and easy to use.

Dollars and sense: Bigstep is free. The company makes money by getting a percentage when customers buy partner products. Later this year Bigstep will begin optional offering enhanced Web site tools and services for a fee. To attract customers, Bigstep has partnerships with the Direct Marketing Association, Small Business Administration and Bank First USA.

If he builds it, will they come? Since its July 1999 launch, Bigstep has signed more than 30,000 businesses as customers. Growth potential is substantial: Analysts estimate that only 10 percent of U.S. small businesses (those with less than 100 employees) have an online presence.

Finding funding: The Washington Post Co., along with various venture capitalists and individuals, ponied up about $11 million.

A day in the life: As CEO, Beebe's mission involves basic founder duties—working until 2 a.m., evolving the business plan, signing partners, raising capital. Only one problem. "I've never managed a person in my life up until this company," Beebe says. So far, though, no sweat. His new-school management techniques—which include ritual Friday barbecues and staff toy-buying budgets—seem to do the trick for Bigstep's 65 staffers. College major: Political science

JON CALLAGHAN '91

General Partner, CMGi's@VenturesMenlo Park, California

Net-related business: "All we do is Internet stuff," says callaghan, one of Silicon Valley's youngest venture capitalists. As one of the hidden powerhouses behind many Internet companies that have become household names over the past four years, ©Ventures' nine partners are known for their incredible savvy in appraising new business plans. And they have plenty of cash in their piggy bank: Callaghan and his fellow VCs have roughly $3 billion in four funds at their disposal to invest in Internet startups. (©Ventures is linked to Andover, Massachusetts-based CMGi.)

The vision thing: "We ain't seen nothing yet on the Internet," Callaghan says. Given his firm's strong track record thus far, the future could be outrageous. Already © Ventures' investments in 50 Internet startups—including Auction Watch, Furniture.com, Planet Outdoors and Geo Cities (bought by Yahoo! for more than $4 billion)—have shown a whopping 3,000-percent return-on-investment. Looking for a good stock? See if ©Ventures has funded the company. Interested in taking some Internet risks? Ditto. (As of press time, Callaghan's firm hadn't made any investments in the other dot-coms profiled in this article.)

How he got where he is today: During the summer of 1996, as a Harvard business school student, Callaghan took a job at CMGi. He returned to Harvard the next year, co-wrote the business plan that became the foundation for Chemdex.com, a business-to-business site for chemical suppliers and buyers, and won runner-up honors at Harvard's business plan competition. After graduating, Callaghan resigned from Chemdex and rejoined CMGi, where he saw to it that Chemdex got funding.

A day in the life: Callaghan says he enjoys helping entrepreneurs start their own businesses rather than founding his own. "I'm much more proud to be helpful to new companies, taking those late-night phone calls," he says. "The challenges faced by the startup's entrepreneurs are often over leadership, like getting that Oracle executive to leave a big company to become your lead engineer." While he no longer has time to run Mountain Bike Outfitters in Moose, Montana, a company he founded as an undergrad he and his wife both like outdoor adventures and have traveled to Thailand and New Zealand.

College major: Government; Harvard M.B.A.

TIM CARYCROFT '93

Chief Technology Officer, i-drive.comSan Francisco

Net business: i-drive is one of a handful of new companies that offer consumers free storage space on the Internet, i-drivE, however, offers some unique advantages—such as unlimited storage space and the ability to store MP3 music files. Users essentially have a free Web-based desktop, a place to temporarily or permanently store files that might otherwise live on their home or office PC. The desktop can hold files ranging from e-mail messages to Web page links to professional documents. Users can allow others full or limited access to particular sets of files—handy for collaborators. (This story, in fact, was filed via an i-drive desktop.) Here's another example: A woman who sells items on eBay has more merchandise than she can display there, so she offers a link that eßay shoppers can use to view her goods at her i-drive.

How i-drive makes money: i-drive is free to consumers, but it makes money by licensing its technology to companies and institutions that can co-brand and promote the service, i-drive has inked a deal with 20 colleges—including Case Western Reserve and Stanford—to promote the service to students. "This is like a very stupid version of Lotus Notes," Cracroft says of its usability."

Making it happen: Dartmouth classmate Lewis Cirne '93 (CEO of programming company Wily Technology in Santa Cruz, California) introduced Craycroft to i-drive CEO Jeff Bonforte in 1998. Craycroft quickly became partner. They brought on three additional founders ("Gray-haired men who lend us credibility," says Craycroft) and began to advance their plan. The idea was to create a storage area on the Internet that could be accessed from any Internet connection, eliminating the need to carry a laptop and disks. Craycroft's job: creating an easy to use architecture that would let users (such as college students and travelers) transfer and store files on the i-drive system. The service was up and running last August.

A day in the life: What life? This was summer 1999: "For six weeks or so I spent about four hours a night under my desk," Craycroft says. "You fall asleep on your chair, wake up on the ground and get going again." During the day he had to wear his CTO hat and join the company's co-founders to schmooze with investors and explain i-drive's technology to business partners. And oversee the firm's growth (currently 60 employees). Of course, Craycroft isn't complaining. "Here my success and the company's success are the same thing," he says. "I will never work for a big company again." Now he can plan a much-needed ski vacation and wait on his patent for Filo, an i-drive feature Craycroft created that captures and stores favorite Web pages.

Finding funding: The company got rolling with an undisclosed round of seed money before raising $4.5 million; a second round of funding just rustled up another $l5 million

College major: Computer science

CHRIS ALDEN '92

CEO and President, Red Herring San Francisco

Net-related bufsiness: Red Herring magazine, a hot monthly read for anyone in the Internet trenches, is one of the first magazines to successfully marry business and technology. Since the magazine's 1993 debut, numerous other tides—each examining a slightly different angle—have appeared on the scene. Alden isn't worried about a crowded market. The magazine now has about 200,000 subscribers. With revenue from its conferences, Web site and advertising, it turned profitable in 1998—just five years after launching. Stories don't all focus on Internet companies, though the Net does loom large in coverage. The 440-page March 2000 issue, for example, featured a cover story about a new microchip.

What kind of name is that? The Red Herring title comes from a 1920s term for a new company's somewhat incomplete-and therefore risky—prospectus.

The vision thing: The summer he graduated, Alden sat down at his new 21-inch color Macintosh computer—a gift from his parents—and began forming a new business with a Stanford pal. The pair hooked up with Tony Perkins, founder of a technology monthly called Upside Magazine, and started publishing their magazine. "We worked out of my house and didn't take salaries," explains Alden. "We managed to get our advertisers to pay up front, before we had to pay the printing bill. As our ad base grew, we grew the company." Alden says he's always had an interest in entrepreneurship, both as a vocation and as a subject of journalistic debate. Hence Red Herring's mission: "The idea was to create a magazine that covered technology, venture capital and entrepreneurialism, "he says. "What we're really doing is covering the business trends for the future."

College major: History

FINE TUNING FINANCE; MARK MOELLER

ANIMAL INSTINCT: ANDREA REISMAN

SPAM TERMINATOR: DAVID KRAMER

CAPITAL ACHIEVER: JON CALLAGHAN

PRINT RENEGADE: CHRIS ALDEN

Jane Hodges has written about business for Fortune, Business 2.0, Advertising Age and Small Business Computing.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureIt’s the Ideas, Stupid

April 2000 By KEITH H. HAMMONDS ’81 -

Feature

FeatureHorton Hears a Heil

April 2000 -

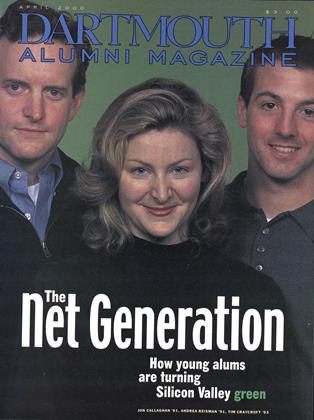

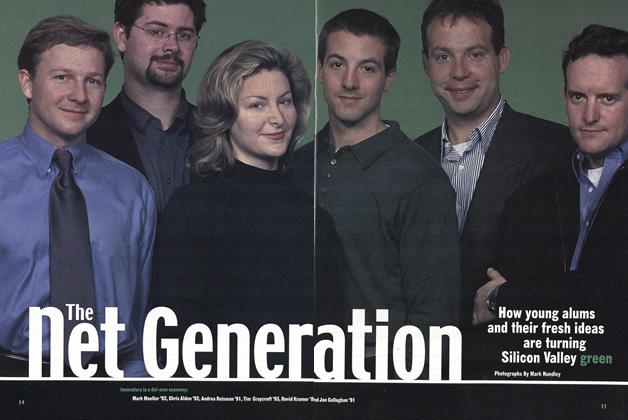

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Net Generation

April 2000 By Jane Hodges ’92 -

Article

ArticleThe Power of Philanthropy is the Power of Growth

April 2000 -

SYLLABUS

SYLLABUSRewriting Violence

April 2000 By Courtney Cook Williamson ’93 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1990

April 2000 By Jeanhee Kim, Sanda Lwin, Ramzi Nemo

JANE HODGES '92

-

Article

ArticlePanting For Credit

MARCH 1992 By Jane Hodges '92 -

Article

ArticleSeniors Interview Their Elderly Future Selves

MAY 1992 By Jane Hodges '92 -

Article

ArticleWe asked 53 students: "Would You Send Your Child to Dartmouth?"

June 1992 By Jane Hodges '92 -

Cover Story

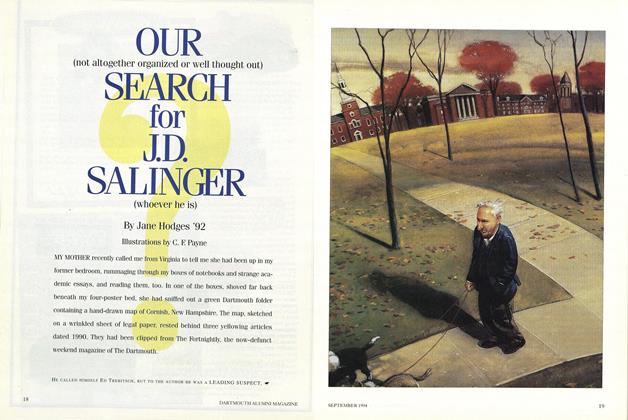

Cover StoryOUR SEARCH FOR J.D. SALINGER

SEPTEMBER 1994 By Jane Hodges '92 -

Feature

FeatureLooking for Mister Right Stuff

Novembr 1995 By Jane Hodges '92 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryM. Lee Pelton

OCTOBER 1997 By Jane Hodges '92

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Inauguration

NOVEMBER 1998 -

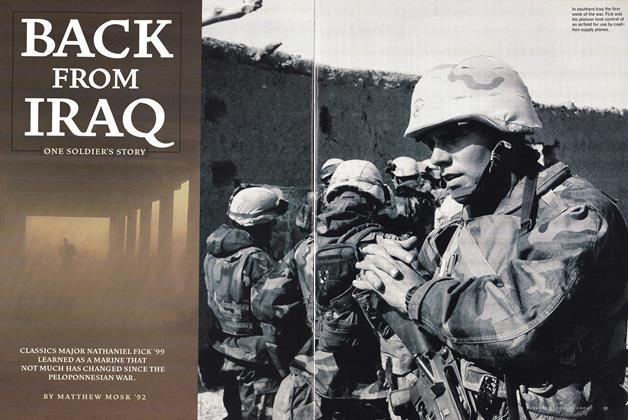

Cover Story

Cover StoryBack From Iraq

Jan/Feb 2004 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Feature

FeatureCenters of Excellence and the Survival of Creativity

APRIL 1984 By O. Ross Mclntyre '53 -

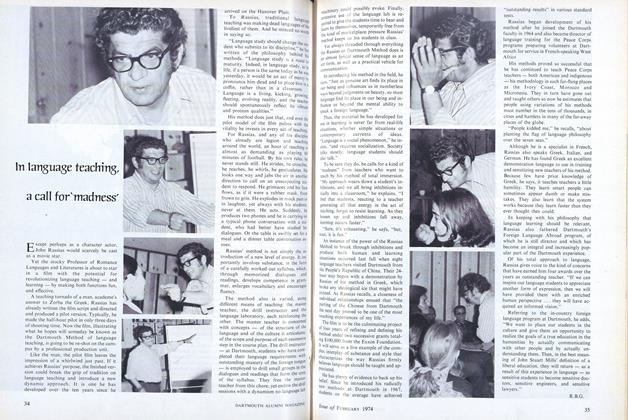

Feature

FeatureIn language teaching, a call for ‘madness'

February 1974 By R.B.G. -

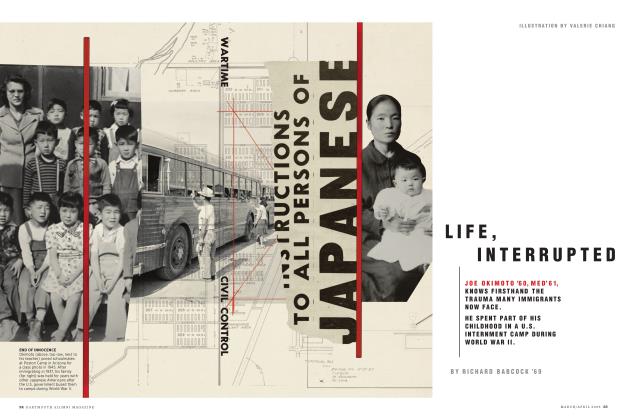

FEATURES

FEATURESLife, Interrupted

APRIL 2025 By RICHARD BABCOCK ’69 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO WASH YOUR DOG LIKE A PRO

Jan/Feb 2009 By RUSH '05 & JAMES TURNER '04