Two Years Before The Mast

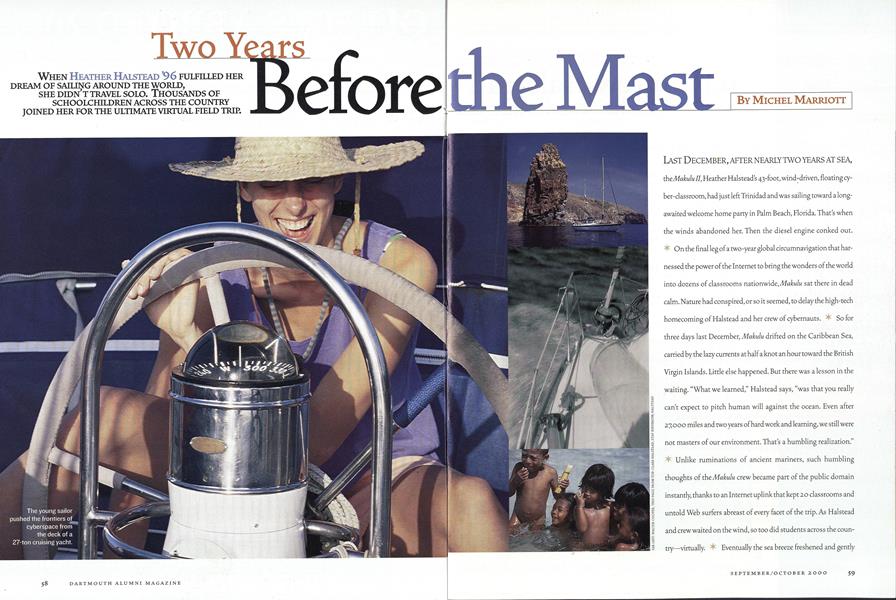

When Heather Halstead ’96 fulfilled her dream of sailing around the world, she didn’t travel solo. Thousands of schoolchildren across the country joined her for the ultimate virtual field trip.

Sept/Oct 2000 Michel MarriottWhen Heather Halstead ’96 fulfilled her dream of sailing around the world, she didn’t travel solo. Thousands of schoolchildren across the country joined her for the ultimate virtual field trip.

Sept/Oct 2000 Michel MarriottWHEN HEATHER HALSTEAD 96 FULFILLED HER DREAM OF SAILING AROUND THE WORLD, SHE DIDN T TRAVEL SOLO. THOUSANDS OF SCHOOLCHILDREN ACROSS THE COUNTRY JOINED HER FOR THE ULTIMATE VIRTUAL FIELD TRIP.

LAST DECEMBER, AFTER NEARLY TWO YEARS AT SEA, the Makulull, Heather Halstead's 43-foot, wind-driven, floating cyber-classroom, had just left Trinidad and was sailing toward a longawaited welcome home party in Palm Beach, Florida. That's when the winds abandoned her. Then the diesel engine conked out. * On the final leg of a two-year global circumnavigation that harnessed the power of the Internet to bring the wonders of the world into dozens of classrooms nationwide, Makulu sat there in dead calm. Nature had conspired, or so it seemed, to delay the high-tech homecoming of Halstead and her crew of cybernauts. So for three days last December, Makulu drifted on the Caribbean Sea, carried by the lazy currents at half a knot an hour toward the British Virgin Islands. Little else happened. But there was a lesson in the waiting. "What we learned," Halstead says, "was that you really can't expect to pitch human will against the ocean. Even after 27,000 miles and two years of hard work and learning, we still were not masters of our environment. That's a humbling realization." * Unlike ruminations of ancient mariners, such humbling thoughts of the Makulu crew became part of the public domain instantly, thanks to an Internet uplink that kept 20 classrooms and untold Web surfers abreast of every facet of the trip. As Halstead and crew waited on the wind, so too did students across the country—virtually. Eventually the sea breeze freshened and gently blew the Makulu to the British Virgin Islands, where her engine was repaired. The journey continued, and the crew made landfall in time for its homecoming gala.

The Palm Beach gala marked the end of a quest that began long before Halstead even set sail. What drew her to the sea is a tale that rings familiar with Dartmouth alumni. It begins with the perennial student question: "What am I going to do when I graduate?" In hours of fantasy, seniors dream up extreme kayak adventures or ascents of the world's tallest peaks. Halstead s drem was a circumnavigation of the world aboard a sailboat. Unlike many who postpone their dreams until retirement, Halstead had the drive, expertise, imagination—and resources—to go for it right out of college.

"I realized that if I really wanted to pursue this dream now, I could do it. I wasn't an expert on bluewater cruisers, and I had only ever done one overnight passage in my life," she explains. "It would be hard, but I decided I could do it because I had enough basic knowledge to give it a responsible try. Then we forged ahead with the myriad other things we had to learn, all in the spirit of how I was trained to think about expeditions by the Dartmouth Outing Club when I was there."

Unlike John Ledyard (class of 1780), Dartmouth's prototypical sailing professional who joined Captain Cooks crew, Halstead became the leader and outfitter of her own expedition. It was Halstead who combined some inheritance money from her seafaring grandfather with a "massive loan" she's still financing to purchase Makulu, a 27-ton, Nautor-Swan cruising yacht. It was Halstead's idea to outfit the 22-year-old boat with the necessary electronics to link the ship to a network of classrooms. She also recruited the crew, including captain Marc Gustafson, a 22-yearold sailing instructor and a graduate of the Chapman School of Seamanship. And it was Halstead who started a non-profit company, Reach the World, to oversee the educational mission she envisioned for her voyage.

Reach the World isn't the only group exploring the Internet's potential as a teaching tool. NASA, for instance, created a program that lets high school students drive a prototype of the Mars rover across the Nevada desert using the same software as NASA engineers. And the JASON Project, created by Dr. Robert Ballard, discoverer of the Titanic's sunken remains, hosts interactive, virtual scientific expeditions offering students the chance to communicate with real scientists. What set Halsteads project apart is how teachers and students drove the content. "The trip was an experiment in how to make an Internet resource that was totally responsive to an individual teachers needs," explains Halstead. "Besides, when things got bad on the boat, there was always something to explore for a classroom of sixth-graders, or a kid on e-mail asking why the boat didn't get eaten by sharks."

Sixth-graders in Heather Ganek's Washington Heights, New York, classroom exemplify this cooperative, do-it-yourself spirit. The class wanted to "do" Singapore, so the students developed a list of places they wanted to see, planned a schedule and a budget, and e-mailed an entire itinerary to the Makulu crew.

"Their schedule was so cute," recalls Halstead. "It even included tips on transportation and time for coffee breaks. When we finished our day, we put together a package of Web pages embedded with digital photos for them. They were able to look at the pages the next day in class."

By its fourth semester at sea, the Makulu crew had mastered this fine art of high-tech with a personal touch. Halstead established digital dialogues with educators, students and anyone else interested in conversing directly with the voyagers. "We deliberately kept it small—no more than 20 teachers each semester," she says, "so we could research themes and produce content exactly along the lines of what the teachers wanted." The result of these partnerships was a Web site that hundreds of other schools used throughout the voyage.

This approach enabled Halstead to position the Makulu and her crew in cyberspace right alongside more famous and better-funded institutions. "This almosthomegrown effort might be a sign of things to come, as legions of adventurers begin to offer globe-trotting services to schools," declared EducationWeek in September 1998, nine months after Makulu first set sail. The voyage also caught the attention of The New York Times and The Christian Science Monitor.

"It was a wonderful experience for my students to be able to feel a connection to real people as they studied the classroom maps," says Pat Palazzolo. Her ninth-graders at the Upper St. Clair High School in St. Clair, Pennsylvania, were on the receiving end of West African legends about the sky collected and transmitted by the Makulu crew when it was in Senegal and Morocco. "My students were fascinated by the idea of people not much older than themselves involved in such an adventure," adds Palazzolo.

Halstead's own learning curve stretches to today. At home in New York, she sounds somewhat conflicted as she reflects on the voyage. "To be honest, even though it was my dream, I quickly found that it was a lonesome path, and disconnected from what had defined me back at home," she says. "But by the end of the voyage I realized, or rather accepted, that it was okay to feel a sense of alienation from my home world, and a desire to be back in it. It was natural because my dream-world didn't necessarily contain the intelligent, discursive community that had supported me and made me grow at Dartmouth—the kind of community I needed in order to be my most productive."

Following graduation Halstead ignored pressure to join what she refers to as "the pantyhose set" of corporate America. But today she is exploring the periphery of the business world, albeit on her terms. She's launched a for-profit, content production company, Makulu Ventures, which will work in partnership with Reach the World to run a second world voyage of Makulu next year. "Our idea for the next voyage is to add a documentary-style TV series that is as close to real time as possible from the boat," she says. "The real lure for kids, not for teachers and educators, is the entertainment value of getting to know the people on board. I feel that if you can successfully bring an educational mission into entertainment, then why not?"

Is Halstead selling out? Not at all. "A lot of people raise an eyebrow when they hear 'for-profit' and education' in the same breath," she said via e-mail from aboard the Makulu last June while battling stormy seas. She was bringing the boat up the East Coast to its summer port in Connecticut. "We did not adopt the structure to become millionaires. We did it because we felt it would help us move fast, create something better and capitalize on the general health of the economy. If we're successful, we will be able to develop more learning adventures similar to the first circumnavigation."

When Makulu sets sail for another educational voyage around the world, Halstead doesn't expect to be part of the full-time crew. She instead envisions a behind-the-scenes role for herself. "There are so many new things to learn, it's overwhelming," Halstead says. "It's just like starting out on the first voyage, only it's a differentset of skills."

The young sailor pushed the frontiers of cyberspace from the deck of a 27-ton cruising yacht.

SEA OF GREEN Dartmouth alumni werewell-representedon the Makulu II crew:DENNY DENNISTON '61TODD PARMENT '95ANDREW SWANSON '95JUSTIN WELLS'95DAVE LABRADOR '96MARGARET WHEELER'97JASON DEMOS'97HANS KIESERMAN '97AMANDA PAULSON '97TOM DENNISTON '02 JACK DOWNEY'03

CHARTING A COURSE Halstead's two-yearjourney began on January 9,1998, with a short hop fromMiami to Marathon,Florida. From there theMakulu II headed west(see map below) beforereaching Palm Beach onDecember II, 1999.

Halstead has set her sights on broadening her educational ventures. Another circumnavigation is already in the works.

to the sea is a tale that rings familiar with Dartmouth alumni.

MICHEL MARRIOTT is a reporter for the Circuits section of The New York Times.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

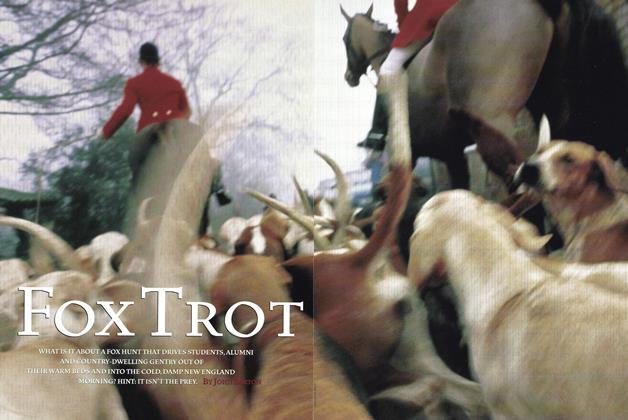

FeatureFox Trot

September | October 2000 By John Barton -

Cover Story

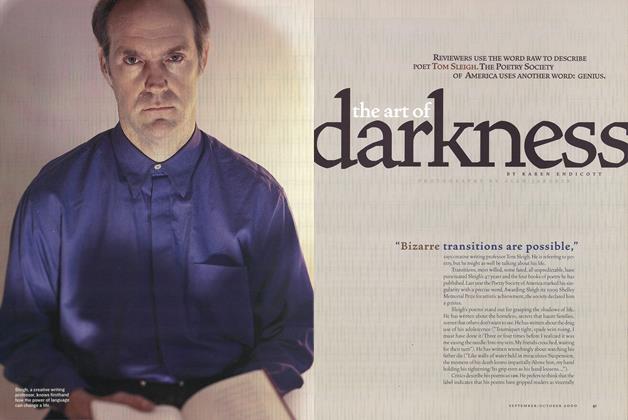

Cover StoryThe Art of Darkness

September | October 2000 By KAREN ENDICOTT -

Feature

FeatureCommencement and Reunions: A Sketchbook

September | October 2000 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYWhat is Perfect?

September | October 2000 By Mary Cleary Kiely ’79 -

Sports

SportsMaking all the Right Moves

September | October 2000 By Brad Parks '96 -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMCode of Life, Codes of Conduct

September | October 2000 By Karen Endicott

Features

-

Feature

FeatureLOST IN THE TREASURE ROOM

OCTOBER 1998 By Brock Brower '53 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO FIND YOUR INNER DOWNWARD FACING DOG

Jan/Feb 2009 By DIANA (SABOT) WHITNEY '95 -

Feature

FeatureYou Can Go Home Again

November 1974 By DICK REDINGTON '64 -

Feature

FeatureEgyptologist

DECEMBER 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

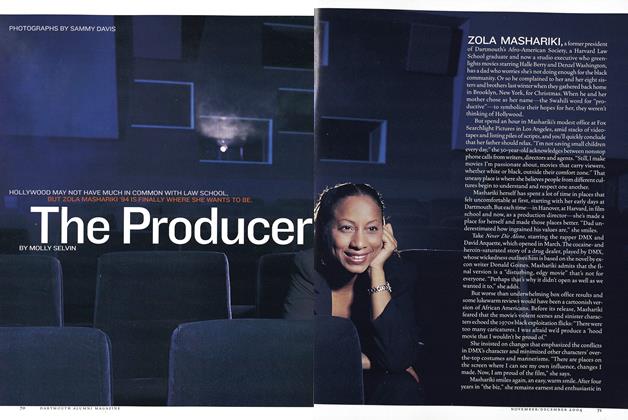

FeatureThe Producer

Nov/Dec 2004 By Molly Selvin -

Feature

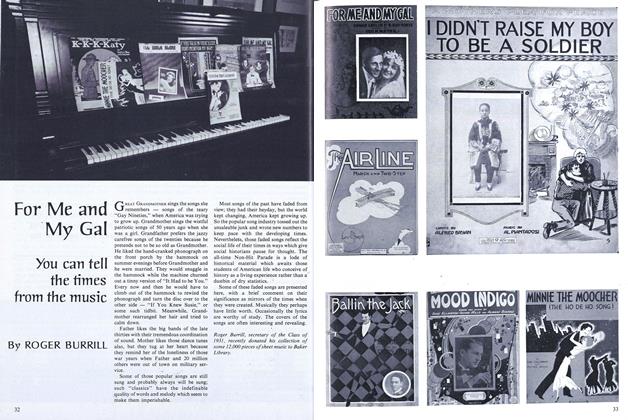

FeatureFor Me and My Gal

October 1976 By ROGER BURRILL