To Be a Lazy European

An economist busts some myths about why Americans seem to work harder and longer than Europeans.

Jan/Feb 2007 Bruce Sacerdote ’90An economist busts some myths about why Americans seem to work harder and longer than Europeans.

Jan/Feb 2007 Bruce Sacerdote ’90An economist busts some myths about why Americans seem to work harder and longer than Europeans.

IF YOU ARE LIKE MOST AMERICANS you grabbed a week or two off this past summer, rather than the expansive August-plus-part-of-July vacation that your European counterparts took. Maybe the espresso-drinking, Vespa-riding, fashion-conscious socialists have figured out something we haven't.

My coauthors (Edward Glaeser and Alberto Alesina) and I have written a series of papers on why life in the United States and Europe is so different. Our latest installment addresses the huge differences in hours worked. If we include all people ages 15-64, Americans are working an average of 25.1 hours per week vs. 18.0 for the French and 16.8 for the Italians. That's a large gap. But in researching the causes behind the gap, we find a series of facts that help debunk several myths.

First, contrary to the image of the overworked American, in a "usual" or non-holiday week fulltime workers on both continents work almost the same amount, and its not terribly far from a 40-hour workweek. Usual hours for the fulltime employed are 39 per week in the United States vs. 36 for the French and Germans and 37 for the Italians. Readers of this magazine might be working 50 or 60 hours per week but are probably not a random sample of all Americans. Only one quarter of the total gap in hours worked comes from the full-time employed in the United States working more hours in a "usual" or non-holiday week.

In contrast, 45 percent of the overall difference in hours worked comes from our much smaller number of vacation and holiday days. We work, on average, 46 weeks per year vs. 40 weeks for the Europeans. Of that six-week difference, about one week consists of the additional holidays granted by European employers relative to U.S. employers. The remaining five fewer weeks of work is pure vacation time, and much of it federally mandated. Italy and Germany require that full-time employees get at least four weeks of vacation, while France requires five weeks. So it's really the generous vacation time in Europe that makes the biggest difference, not Frances famous 35-hour work week.

A second myth about work in Europe vs. the United States is the notion of a longstanding cultural difference in work ethic between the two places. The truth is that the large difference in hours worked is a relatively new phenomenon. As recently as 1962 Europeans were working more hours per week than Americans. Saturday work was quite common on both continents. As both societies became richer and more productive per hour worked, both places cut back on total hours worked. However, starting in the mid-1970s hours worked fell much more rapidly in Europe.

My co-researchers and I believe the divergence in work habits is connected to the power of unions in Europe and the ability of those unions to serve as a coordinating device to expand the amount of vacation taken by all workers across all sectors. Vacation time is much more enjoyable if ones spouse or friends can share that time. And it's easier to get away from the office if no one else is working and sending you 60 e-mails per day. That's the inherent beauty of the European system: There's no guilt in being on extended vacation since no one else is at the office sending you urgent e-mails and voicemails.

In a sense, the Europeans have taken much of the recent economic gains from increased productivity and efficiency in the form of more leisure. Americans have taken the same gains in the form of better houses, cars and televisions. The notion that the Europeans have figured out a way to work one and a half months less per year while enjoying the same level of consumption as Americans is not true. Our 2004 income per capita was about $39,700, which is 17 percent more than the average for the United Kingdom, France and Germany. But the gap is a much bigger 33 percent when you account for the fact that housing, goods and services are simply cheaper here.

Various authors claim that Europeans are engaged in work at home while Americans purchase those household services (and count them in our income and hours-worked statistics), so that it is all largely a wash. This is easily checked using time-diary data; and I can report that while it's true that we eat at restaurants more—and cook less—Americans spend the same amount of time or more cleaning and fixing the house. Europeans just have more leisure time, and they spend it with their family and friends.

By at least some measures the Europeans are on to something. My colleague, Dartmouth economics professor Danny Blanchflower, points out that 46 percent of Americans say they would like to have much more time with their families vs. 36 percent for the British and 26 percent for the Germans. And he points to recent evidence that American men have higher blood pressure than British men. However, it's also true that on both continents around 30 percent of people report that they are very happy and another 58 percent are pretty happy. So any notion that the Europeans are vastly happier is hard to see in the data.

Should the United States mandate copious amounts of vacation time the way most European countries do? The answer is far from obvious. First, it's difficult to say which system is better; they're just different. Second, given the U.S. culture of work, many people don't even use the vacation days to which they are already entitled. Increasing the entitlement would have a significant effect only if everybody decided collectively to take the extra vacation. Third, part of the great economic success of the United States and its accompanying high employment rate stems from the flexibility that workers and firms have to devise their own contracts. The United States is a nation in which a great deal of productive work is performed by part-time telecommuters, partially retired folks and students on summer break. More government laws restricting the nature of those creative contracts means less choice and flexibility.

The United States won't be switching to the European model anytime soon, so when you leave for the beach next summer, you may still have to take your laptop along for the ride.

BRUCE SACERDOTE is vice chair ofthe economics department. His Web site iswww.dartmouth.edu/~bsacerdo.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

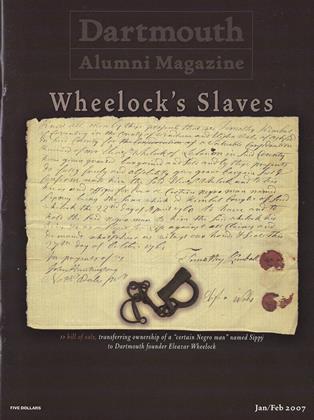

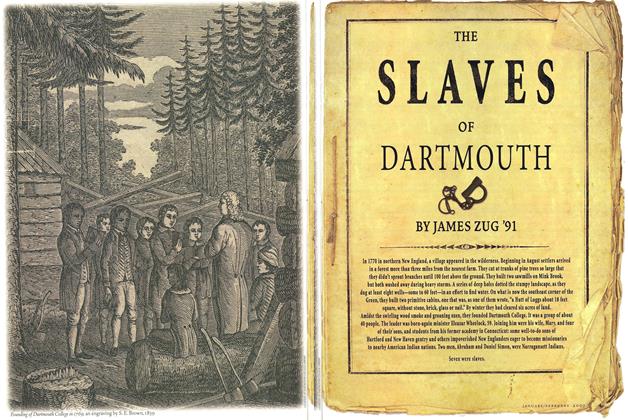

Cover StoryThe Slaves of Dartmouth

January | February 2007 By JAMES ZUG ’91 -

Feature

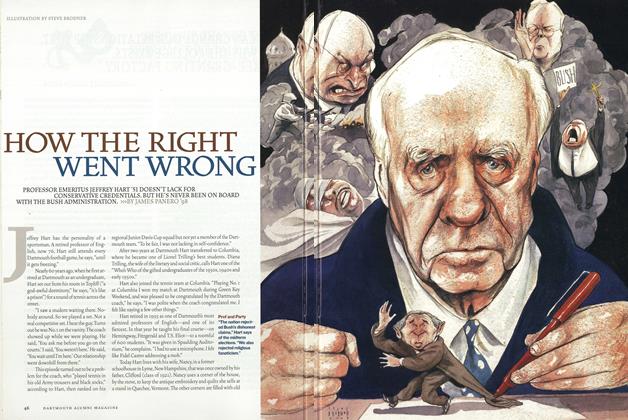

FeatureHow the Right Went Wrong

January | February 2007 By JAMES PANERO ’98 -

Feature

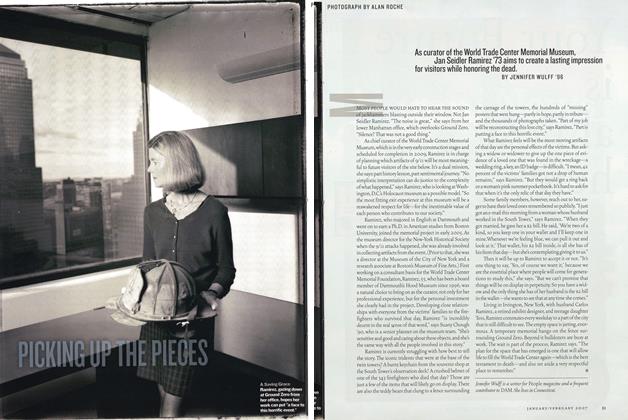

FeaturePicking Up the Pieces

January | February 2007 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

January | February 2007 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

January | February 2007 By William Landmesser '74 -

Interview

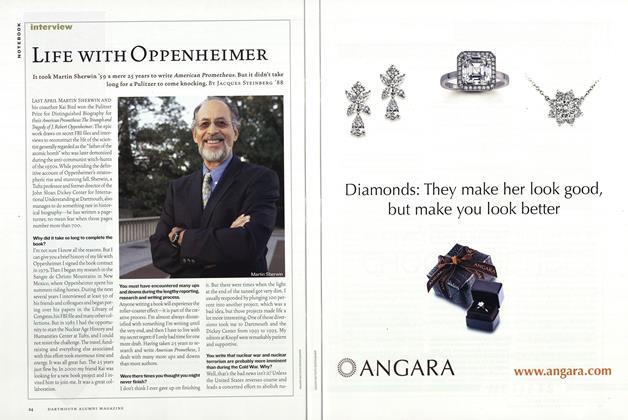

InterviewLife with Oppenheimer

January | February 2007 By Jacques Steinberg '88

FACULTY OPINION

-

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONMillennial Mindset

May/June 2007 By Aine Donovan -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONSlow Medicine

May/June 2009 By Dennis McCullough, M.D. -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONA Sorry State of Affairs

Jan/Feb 2008 By Jennifer Lind -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONShiny Bubble

May/June 2005 By JOHN H. VOGEL JR. -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionThe Cost of Winning

Mar/Apr 2003 By Professor Ray Hall -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONMyths of Innovation

Mar/Apr 2006 By Vijay Govindarajan and Chris Trimble