The Iraq Question

Do the dangers posed by rogue nations with weapons of mass destruction merit an attack?

Nov/Dec 2002 Daryl G. PressDo the dangers posed by rogue nations with weapons of mass destruction merit an attack?

Nov/Dec 2002 Daryl G. PressDo the dangers posed by rogue nations with weapons of mass destruction merit an attack?

THE UNITED STATES IS PREPARING for war against Iraq. As this goes to press, the Bush administration has not yet made a final decision, but war seems likely. The Bush team has marshaled several justifications for military action: Saddam Hussein is a brutal dictator who abuses his own people, flouts international law and thumbs his nose at the United States. The administration has also tried to link Saddam to Al Qaeda or to the September 11 attacks, with little success. Al Qaedas leaders hate Saddams secular government nearly as much as they loathe the United States and Israel. Al Qaeda recruitment videos reportedly single out Saddams government as one of the evil regimes that must be destroyed. Absent compelling evidence to the contrary, there's no reason to believe that Saddam was involved in the September 11 attacks.

The strongest rationale for war is that Saddam is committed to developing chemical, biological and nuclear weapons. Advocates of invasion argue that the United States should use any means necessary, including military force, to remove Saddam from power before he gets these weapons of mass destruction and becomes an even bigger problem.

However the current crisis is resolved, Iraq is not an isolated problem. Many dictators already have chemical or biological weapons, and several seem interested in nuclea rweapons.This trend raises perhaps the most important foreign policy dilemma now facing the United States: What should the United States do to prevent the spread of weapons of mass destruction to unfriendly countries?

In the case of terrorists, the United States is using, and should continue to use, all the instruments of foreign policy—including military force—to prevent them from obtaining or using weapons of mass destruction

In the case of hostile dictators, however, the United States should not use military force to prevent or reverse acquisition of chemical, biological or nuclear weapons.

Four arguments lead to this conclusion. First, logic and history suggest that a Third World dictator is very unlikely to use weapons of mass destruction against the United States or a U.S. ally—unless we push his back up against the wall. Second, it is not a simple task to de-fang a country that is developing weapons of mass destruction; only invasion, conquest and long-term occupation of the enemy will prevent or reverse the proliferation of these weapons. Third, attempts to conquer Third World dictators are likely to inc. ase the odds of biological, chemical or nuclear attacks on Americans and U.S. allies. Finally, a policy of preventive attacks on rogue states may alienate America from its closest friends abroad and undermine progress in Americas war on terror.

If military strikes are not the answer, what is? The best course is to adopt the policy that served America so well throughout the Cold War: containment. We should build alliances around the rogue states, prevent them from conquering their neighbors deter them from using their weapons of mass destruction, and wait for their corrupt regimes to collapse.

Critics of containment point out that deterrence is not foolproof, and so containment is not risk-free. But none of our options is risk-free, particularly not the option of attacking rogue states. In fact, containing rogue states will pose much smaller risks to America than a policy designed to pry weapons of mass destruction from the hands of dictators.

Let's examine the arguments more closely.

First, logic and decades of history show that unless we push their backs up against the wall, dictators will not use these weapons against either our friends or us. Americans often describe ruthless dictators as "crazy" or "irrational." Brutal dictators certainly do not share our values, but it is misleading to think of them as irrational. Becoming a dictator—and retaining power—requires great cunning. No one survives the treacherous domestic power struggles without a keen ability to evaluate risks and avoid battles that will lead to one's own destruction. Dictators are master practitioners of power politics. This is good news for America, because it means that these dictators understand incentives and deterrence. By explaining very clearly to these rogue leaders that any use of weapons of mass destruction against America or its allies will lead to crushing retaliation, their loss of power and probably their death, we should be able to deter these enemies in almost any circumstance.

The past 50 years demonstrate that nasty dictators can be deterred from using weapons of mass destruction. Mao Tse-tung and Joseph Stalin each murdered tens of millions of their own people; they mercilessly killed people who stood in their way and were too weak to defend themselves. But both of these dictators declined to unleash nuclear weapons against the United States and others who could retaliate. Even Hitler never used his chemical weapons against Britain or allied troops because he feared the repercussions. For decades North Korea's brutal leaders have stockpiled chemical and biological weapons, but they have not used them against U.S. forces or allies in the region. Both Syria and Libya have possessed chemical weapons for decades, but neither has used them against Israel, their sworn enemy.

Evidence from Saddams own behavior also supports this argument. During the 1991 Gulf War, Saddam aimed chemical and biological weapons at Israel and at the American military forces in Saudi Arabia. Here's a man who used chemical weapons against Iraqi Kurds and Iranians, but when facing the prospect of American or Israeli retaliation, he wisely decided against using them. Senior members of Saddams government, who defected after the war, confirm the reasoning behind Saddams decision not to use chemicals or germs in 1991: Saddam was afraid that America might respond with nuclear weapons.

When it comes to Third World dictators the historical record is clear: they're bullies. They prey on the weak but act quite rationally when facing people with the power to demolish them.

A second argument against military action is that it will be far harder than many people imagine. Destroying a country's weapons program is not easy because the weapons and the facilities used to develop them are easy to hide. The United States learned this lesson during the Gulf War; after the war we discovered that most of Iraq's chemical, biological and nuclear weapons facilities had been hidden and survived. In July Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld candidly remarked that the problem of locating weapons facilities has not been solved.

The only way to' rid a state of its weapons programs through military action is to conquer it, occupy it, search it and then install and support a government that will remain opposed to restarting this research. In some cases—such as in Iraq—an invasion might turn out to be the easiest part of the mission. And that is only the beginning of a long and costly undertaking.

Third, military action may result in precisely the outcome the United States wants to avoid. If we invade their countries and come after them, even rational leaders may use weapons of mass destruction in a last-ditch effort to save their own lives and their rule. This is precisely why the U.S. military expects Saddam to use chemical and biological weapons against U.S. forces if the United States invades Iraq with the stated goal of toppling his government.

Finally, a policy of attacking rogue states may undermine the war on terror. Our allies around the world have expressed near-unanimous opposition to attacking Iraq—despite the fact that such an invasion is technically sanctioned by international law under existing U.N. resolutions. If the allies won't support an in vasion of Iraq, it is very unlikely that they would support attacks on Iran, North Korea, Libya, Syria or anyone else who is developing weapons of mass destruction.

We cannot afford to alienate our allies. As former National Security Advisor Brent Scow croft recently argued in TheWall Street Journal, America can only hope to win the war on terrorism if we have the enthusiastic support of our allies. Their cooperation is absolutely vital for success at the intelligence work that is needed to track, thwart and destroy Al Qaeda and other dangerous terrorist groups.

America should not be idle while hostile countries build terrible new weapons. The United States should use all of the tools of routine foreign policy to combat the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction. We should work with allies to limit the global trade in bomb-making materials. We should use economic incentives and sanctions to encourage would-be proliferators to abandon their weapons programs. We should support U.N. efforts to curtail nuclear weapons proliferation. And we should vigorously contain any rogue state that gets its hands on these weapons.

Critics of containment argue that a war against Iraq is inevitable, so we should fight now before Iraq gets any stronger. But consider this: In the 1950s senior civilian and military advisors urged President Dwight Eisenhower to launch a war against the Soviet Union for the same reason. They said that war with the Soviets was inevitable, so America should start the war before the Soviets grew too powerful. Eisenhower—who knew more about the horrors of war than any American president since—rejected the advice and continued Americas policy of containment. It was not fast or cheap, but it worked. The Soviet empire collapsed, and an "inevitable" war was avoided.

Before we agree to run the risks associated with fighting several wars to conquer far-away dictators, we should question our reasons for resurrecting the "now or later" logic that Eisenhower rejected 50 years ago. Not all of the policies of the last centuiy will fit the new problems we L.i, but we can learn a lot from the wisdom of previous generations of U.S. foreign policy leaders.

DARYL G. PRESS is an assistant professor inthe government department and a researchfellow at the Rockefeller Center.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Gatekeepers

November | December 2002 By JACQUES STEINBERG ’88 -

Feature

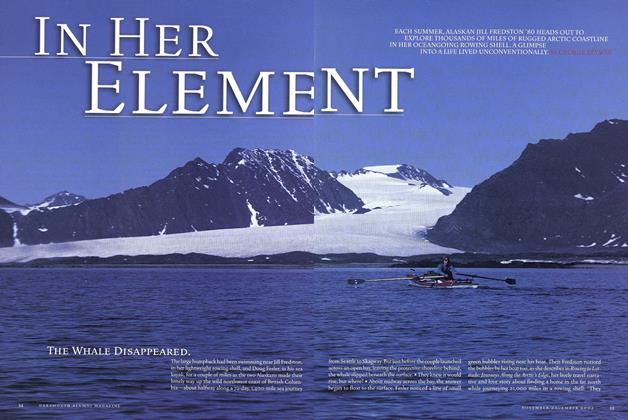

FeatureIn Her Element

November | December 2002 By GEORGE BRYSON -

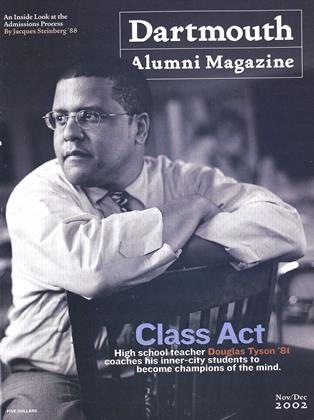

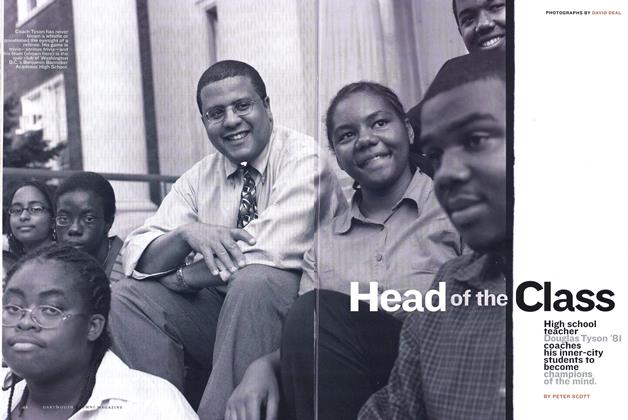

Cover Story

Cover StoryHead of the Class

November | December 2002 By PETER SCOTT -

Classroom

ClassroomThe Art and Science of Group Dynamics

November | December 2002 By Karen Endicott -

Outside

OutsideThe Literature of the Logbooks

November | December 2002 By Madeleine Eno -

Article

ArticleSeen & Heard

November | December 2002

Faculty Opinion

-

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONI Read, Therefore I Think

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2016 By DEVIN SINGH -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONSpeaking in Tongues

May/June 2006 By John Rassias ’49A, ’76A -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionWater Under Fire

July/August 2001 By Joshua Hamilton -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONAmerica Is Queer

Sept/Oct 2011 By Michael Bronski -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONDesigner Genes

Mar/Apr 2008 By Ronald M. Green -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONMyths of Innovation

Mar/Apr 2006 By Vijay Govindarajan and Chris Trimble