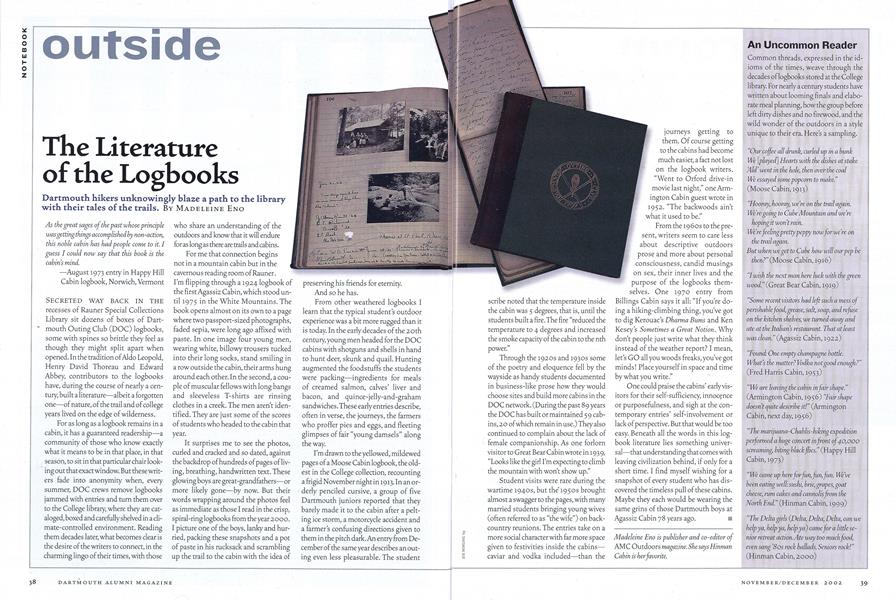

The Literature of the Logbooks

Dartmouth hikers unknowingly blaze a path to the library with their tales of the trails.

Nov/Dec 2002 Madeleine EnoDartmouth hikers unknowingly blaze a path to the library with their tales of the trails.

Nov/Dec 2002 Madeleine EnoDartmouth hikers unknowingly blaze a path to the library with their tales of the trails.

As the great sages of the past whose principlewas getting things accomplished by non-action,this noble cabin has had people come to it. Iguess I could now say that this book is thecabin's mind.

—August 1973 entry in Happy Hill Cabin logbook, Norwich, Vermont

SECRETED WAY BACK IN THE recesses of Rauner Special Collections Library sit dozens of boxes of Dartmouth Outing Club (DOC) logbooks, some with spines so brittle they feel as though they might split apart when opened. In the tradition of Aldo Leopold, Henry David Thoreau and Edward Abbey, contributors to the logbooks have, during the course of nearly a century, built a literature—albeit a forgotten one—of nature, of the trail and of college years lived on the edge of wilderness.

For as long as a logbook remains in a cabin, it has a guaranteed readership—a community of those who know exactly what it means to be in that place, in that season, to sit in that particular chair looking out that exact window. But these writers fade into anonymity when, every summer, DOC crews remove logbooks jammed with entries and turn them over to the College library, where they are cataloged, boxed and carefully shelved in a climate-controlled environment. Reading them decades later, what becomes clear is the desire of the writers to connect, in the charming lingo of their times, with those who share an understanding of the outdoors and know that it will endure for as long as there are trails and cabins.

For me that connection begins I not in a mountain cabin but in the cavernous reading room of Rauner. I'm flipping through a 1924 logbook of the first Agassiz Cabin, which stood until 1975 in the White Mountains. The book opens almost on its own to a page where two passport-sized photographs, faded sepia, were long ago affixed with paste. In one image four young men, wearing white, billowy trousers tucked into their long socks, stand smiling in a row outside the cabin, their arms hung around each other. In the second, a couple of muscular fellows with long bangs and sleeveless T-shirts are rinsing clothes in a creek. The men aren't identified. They are just some of the scores of students who headed to the cabin that year.

It surprises me to see the photos, curled and cracked and so dated, against the backdrop of hundreds of pages of living, breathing, handwritten text. These glowing boys are great-grandfathers—or more likely gone—by now. But their words wrapping around the photos feel as immediate as those I read in the crisp, spiral-ring logbooks from the year 2000. I picture one of the boys, lanky and hurried, packing these snapshots and a pot of paste in his rucksack and scrambling up the trail to the cabin with the idea of preserving his friends for eternity.

And so he has.

From other weathered logbooks I learn that the typical student's outdoor experience was a bit more rugged than it is today. In the early decades of the 20th century, young men headed for the DOC cabins with shotguns and shells in hand to hunt deer, skunk and quail. Hunting augmented the foodstuffs the students were packing—ingredients for meals of creamed salmon, calves' liver and bacon, and quince-jelly-and-graham sandwiches. These early entries describe, often in verse, the journeys, the farmers who proffer pies and eggs, and fleeting glimpses of fair "young damsels" along the way.

I'm drawn to the yellowed, mildewed pages of a Moose Cabin logbook, the old est in the College collection, recounting a frigid November night in 1913. In an orderly penciled cursive, a group of five Dartmouth juniors reported that they barely made it to the cabin after a pelting ice storm, a motorcycle accident and a farmer s confusing directions given to them in the pitch dark. An entry from December of the same year describes an outing even less pleasurable. The student scribe noted that the temperature inside the cabin was 5 degrees, that is, until the students built a fire. The fire "reduced the temperature to 4 degrees and increased the smoke capacity of the cabin to the nth power."

Through the 1920s and 1930s some of the poetry and eloquence fell by the wayside as handy students documented in business-like prose how they would choose sites and build more cabins in the DOC network. (During the past 89 years the DOC has built or maintained 59 cabins, 20 of which remain in use.) They also continued to complain about the lack of female companionship. As one forlorn visitor to Great Bear Cabin wrote in 1939, "Looks like the girl I'm expecting to climb the mountain with won't show up."

Student visits were rare during the wartime 19405, but the' 1950s brought almost a swagger to the pages, with many married students bringing young wives (often referred to as "the wife") on back country reunions. The entries take on a more social character with far more space given to festivities inside the cabins—caviar and vodka included—than the journeys getting to them. Of course getting to the cabins had become much easier, a fact not lost on the logbook writers. "Went to Or ford drive-in movie last night," one Arm-ington Cabin guest wrote in 1952. "The backwoods ain't what it used to be."

1; From the 1960s to the present, writers seem to care less about descriptive outdoors prose and more about personal consciousness, candid musings on sex, their inner lives and the purpose of the logbooks them selves. One 1970 entry from Billings Cabin says it all: "If you're doing a hiking-climbing thing, you've got to dig Kerouac's Dharma Bums and Ken Kesey's Sometimes a Great Notion. Why don't people just write what they think instead of the weather report? I mean, let's GO all you woods freaks, you've got minds! Place yourself in space and time by what you write."

One could praise the cabins' early visitors for their self-sufficiency, innocence or purpose fulness, and sigh at the contemporary entries' self-involvement or lack of perspective. But that would be too easy. Beneath all the words in this logbook literature lies something universal—that understanding that comes with leaving civilization behind, if only for a short time. I find myself wishing for a snapshot of every student who has discovered the timeless pull of these cabins. Maybe they each would be wearing the same grins of those Dartmouth boys at Agassiz Cabin 78 years ago.

Madeleine Eno is publisher and co-editor of AMC Outdoors magazine. She says HinmanCabin is her favorite.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Gatekeepers

November | December 2002 By JACQUES STEINBERG ’88 -

Feature

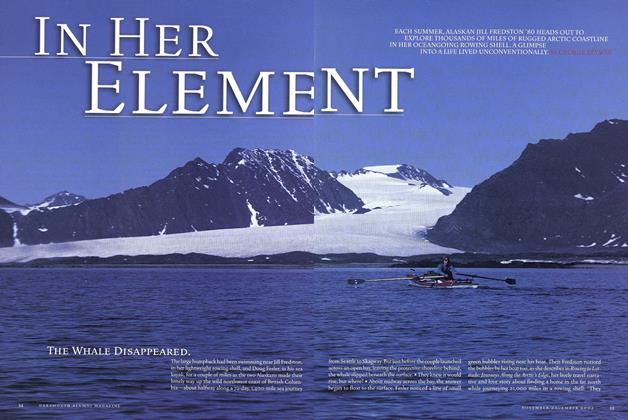

FeatureIn Her Element

November | December 2002 By GEORGE BRYSON -

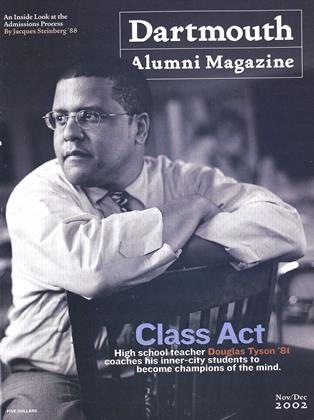

Cover Story

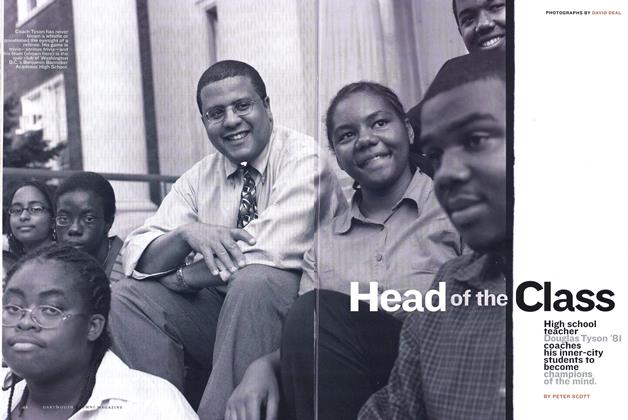

Cover StoryHead of the Class

November | December 2002 By PETER SCOTT -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionThe Iraq Question

November | December 2002 By Daryl G. Press -

Classroom

ClassroomThe Art and Science of Group Dynamics

November | December 2002 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleSeen & Heard

November | December 2002

Outside

-

OUTSIDE

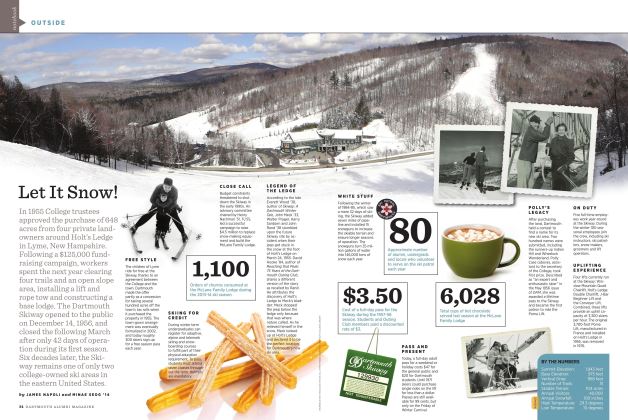

OUTSIDELet It Snow!

JAnuAry | FebruAry -

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDEStill Trippin’

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2014 By ED GRAY ’67 -

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDEOn the Edge

Jan/Feb 2011 By Jonathan Mingle ’01 -

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDEAre You a Chubber?

Jan/Feb 2007 By Lisa Densmore ’83 -

Outside

OutsideGetting the Ax

Sept/Oct 2003 By Lisa Gosseling -

OUTSIDE

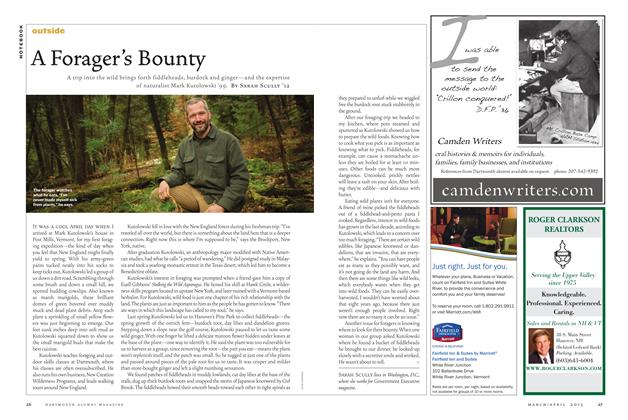

OUTSIDEA Forager’s Bounty

Mar/Apr 2013 By Sarah Scully ’12