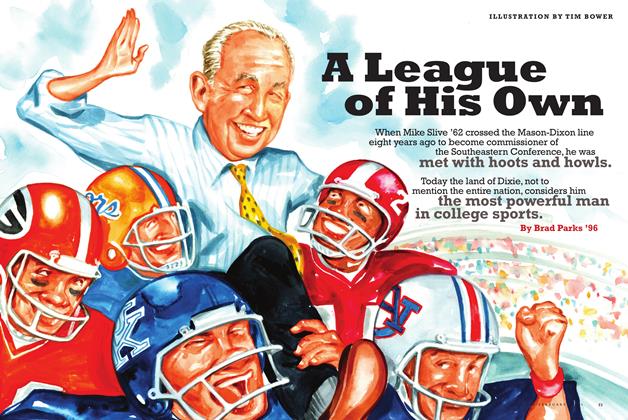

In a League of His Own

Deputy commissioner Bill Daly ’86 never played goalie, but he’s known for making one of the biggest saves in hockey history.

May/June 2009 Brad Parks ’96Deputy commissioner Bill Daly ’86 never played goalie, but he’s known for making one of the biggest saves in hockey history.

May/June 2009 Brad Parks ’96Deputy commissioner Bill Daly ’86 never played goalie, but he’s known for making one of the biggest saves in hockey history.

HIGH ABOVE TIMES SQUARE, IN THE WORLD HEADQUARTERS OF LAW FIRM Skadden Arps, a group of weary sports executives convened at 9 one morning to re- sume negotiations that were already months, if not years, overdue. The date was July 12, 2005, Day 301 of the National Hockey league lockout, a protracted labor dispute that had canned one season and was now jeopardizing another. So Bill Daly, then the NHl’s chief legal counsel, made a deal with his counterpart from the NHl players’ union: They would not leave until they signed an agreement.

thus began what Daly, now the NHl’s deputy commissioner, refers to as “the all- nighter.” it was a 27-hour, adrenaline-and-coffee-soaked negotiating marathon that brought an end to the league’s long labor strife. in what has become clear only in the ensuing years—as the busted league has returned to fiscal soundness—it was also the day-night-day when Bill Daly saved the NHL.

“During a labor negotiation every commissioner has a guy behind the scenes, on the ground, walking all the miles for him. For [NHL Commissioner] gary Bettman, Bill was that guy,” says New jersey Devils owner Jeffrey Vanderbeek. “And when you look at what he was able to achieve, it’s made all the difference for the league.”

Make no mistake: The NHL was in need of saving. Over-expansion and soaring player salaries had stretched many of its teams’ checkbooks to the breaking point. Because, unlike the NFL and NBA, which place limits on what teams can pay players, the NHL was trapped in the same type of collective bargaining agreement as Major League Baseball, without a salary cap. This created a kind of financial arms race that was allowing a few wealthy franchises to spend the rest of the league into oblivion. By the eve of the lockout 19 of the league’s 30 teams were losing money and seven were either in bankruptcy or close to it. Former U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission chairman Arthur Levitt, who prepared a meticulous report on the thrashing, described the NHL as “on a treadmill to obscurity.”

“it’s not a message a commissioner would normally like being broadcast about his league,” Daly says now. “But it was a very accurate description of where the sport was going.”

For Daly, plotting a new course had become a 10-and 12-hour-a-day job for five years. It was a job he loved.

As a kid growing up in central New Jersey Daly was best at football, but hockey was his passion, one he inherited from his Canadian mother and New York Rangers fan father. He was recruited for football at Dartmouth and played tailback all four years, even after a knee injury turned him into a short-yardage plodder. Wanting to stay involved in sports after graduation, Daly went to NYU Law School, then narrowed his job search to the handful of firms that do legal work for the major sports leagues. He became an associate at Skadden Arps, where he spent six years on the NBA, NFL and NHL accounts. Then came the dream job for a lifelong hockey nut: NHL chief legal officer. He landed the gig in 1996, when he was just 32, thanks to strong recommendations from senior partners at his firm who convinced Bettman that Daly was a star on the rise.

“gary took a flier on me, but it was an educated flier,” Daly says. “gary himself had attained a similar position at a relatively young age, so i don’t think age was an obstacle for him.”

By 1999, with hockey’s financial woes becoming apparent, Daly and his legal team started preparing for a future work stoppage. They spent five years researching the issues, drafting different versions of a new collective bargaining agreement and holding mock negotiating sessions.

“i’ve never seen management go into a labor dispute more prepared than the NHL was under Bill Daly and Gary Bettman,” says Jon litner, a former NHl executive who is now president of Comcast Sports Group.

When it finally came time to negotiate with the union Daly’s approach was reminiscent of his style in Dartmouth football coach Joe yukica’s backfield: Straightforward, no-nonsense, practical. And on the key issue—the introduction of a salary cap into the NHL—there could be no bending. “i think the players thought of the lockout as a test of wills, but it wasn’t a test of wills for us,” Daly says. “it was just a necessity. We had no choice.”

It took a lost season of hockey—as well as that full night of negotiation at the end—but the NHl and its players’ union finally came to an accord that included a hard cap on salaries. NHL salaries are now tied to league-wide revenues, which essentially guarantees profitability for all but a few teams.

Four years later, as it prepares to head into the Stanley Cup playoffs, the league has never been healthier. Even in the midst of an economic meltdown, the three main business barometers of any sport—attendance, revenues and television ratings—are all up. Daly, meanwhile, has emerged as Bettman’s right-hand man and heir apparent. Daly downplays the notion he is hockey’s next commissioner—Bettman is only 56, after all—but others say it’s a question of when, not if.

“there’s a lot of credence to that talk,” says litner. “He certainly has the respect of the constituent partners— the owners, the players, the union, the business partners. He certainly has the requisite skills, the work ethic and a passion for the product. The NHL and Gary Bettman recognize that they have a very special guy in Bill Daly.”

Ice Man Daly has emerged as NHL Commissioner Gary Bettman’s heir apparent.

Thanks to his straightforward, practical, no-nonsense style, Bill Daly rescued the NHL.

BRAD PARKS is a freelance writer and author. His first book, a murder mystery, is due out from St. Martin’s Press in December.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA World of Difference

May | June 2009 By CATHERINE FAUROT, MALS’04 -

Feature

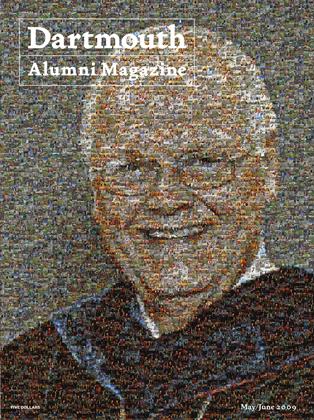

FeatureGod Is in the Details

May | June 2009 By ALEX NAZARYAN ’02 -

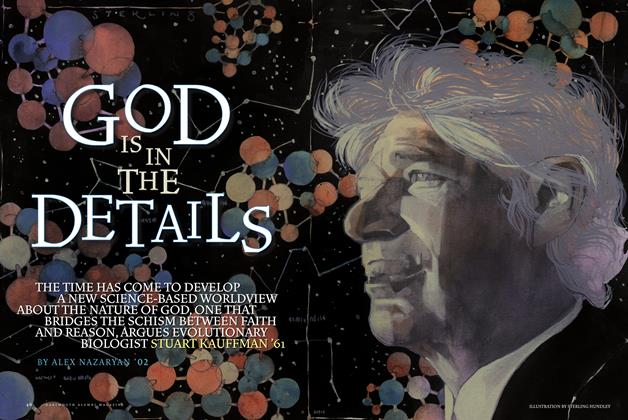

THE DAM INTERVIEW

THE DAM INTERVIEWJames Wright

May | June 2009 By CHRISTOPHER S. WREN ’57 -

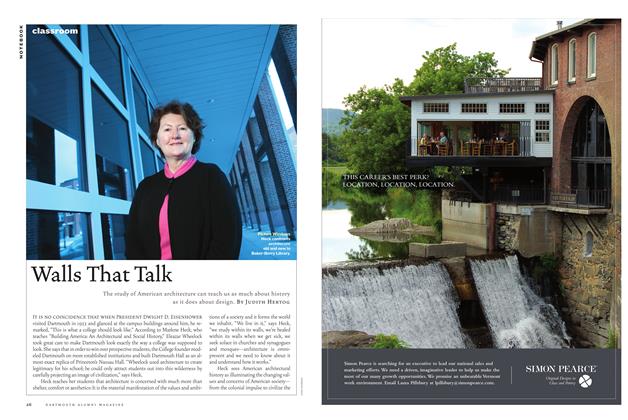

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMWalls That Talk

May | June 2009 By Judith Hertog -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

May | June 2009 By BONNIE BARBER -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONSlow Medicine

May | June 2009 By Dennis McCullough, M.D.

Brad Parks ’96

-

Feature

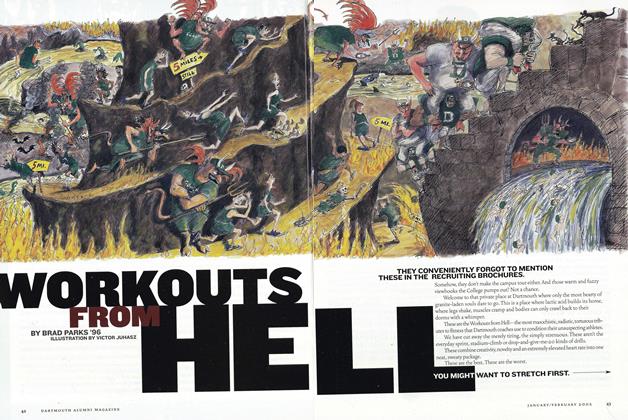

FeatureWorkouts From Hell

Jan/Feb 2002 By BRAD PARKS ’96 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Ones To Watch

Jan/Feb 2010 By Brad Parks ’96 -

Feature

FeatureA League of His Own

Jan/Feb 2011 By Brad Parks ’96 -

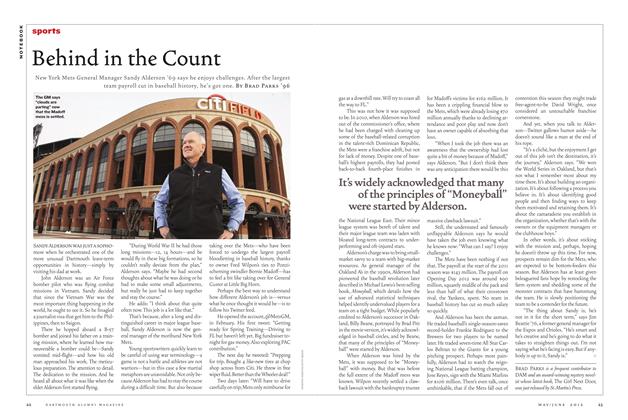

Sports

SportsBehind in the Count

May/June 2012 By Brad Parks ’96 -

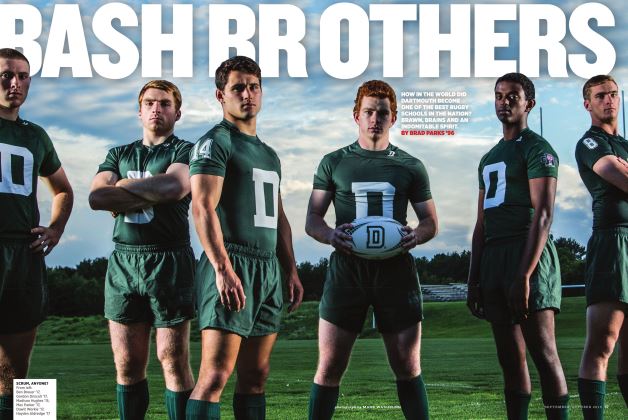

COVER STORY

COVER STORYBash Brothers

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2015 By BRAD PARKS ’96 -

SPORTS

SPORTSGame Changer

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2018 By BRAD PARKS ’96