Shoot to Thrill

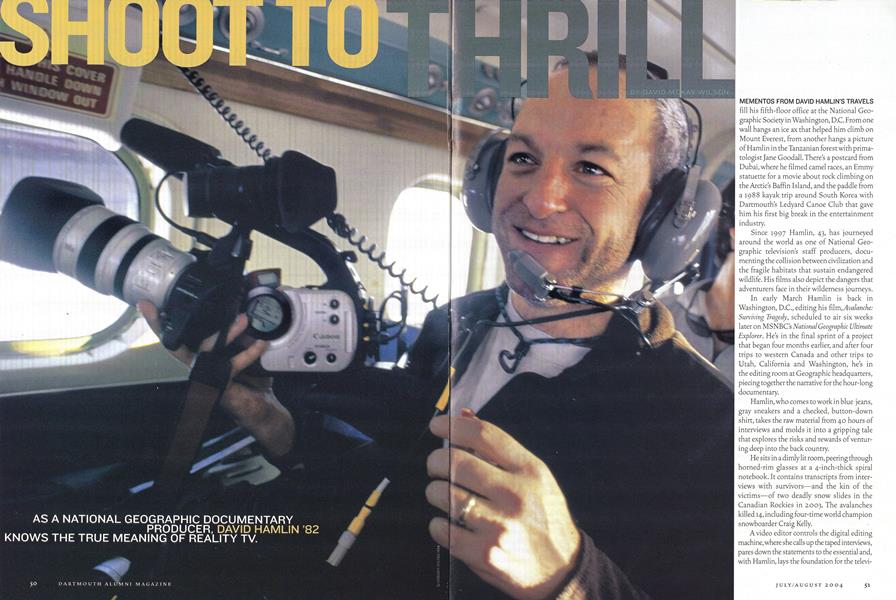

As a National Geographic documentary producer, David Hamlin ’82 knows the true meaning of reality TV.

Jul/Aug 2004 DAVID MCKAY WILSONAs a National Geographic documentary producer, David Hamlin ’82 knows the true meaning of reality TV.

Jul/Aug 2004 DAVID MCKAY WILSONAS A NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC DOCUMENTARY PRODUCER, DAVID HAMLIN '82 KNOWS THE TRUE MEANING OF REALITY TV.

MEMENTOS FROM DAVID HAMLIN'S TRAVELS fill his fifth-floor office at the National Geographic Society in Washington, D.C. From one wall hangs an ice ax that helped him climb on Mount Everest, from another hangs a picture of Hamlin in the Tanzanian forest with primatologist Jane Goodall. There's a postcard from Dubai, where he filmed camel races, an Emmy statuette for a movie about rock climbing on the Arctics Baffin Island, and the paddle from a 1988 kayak trip around South Korea with Dartmouth's Ledyard Canoe Club that gave him his first big break in the entertainment industry.

Since 1997 Hamlin, 43, has journeyed around the world as one of National Geographic televisions staff producers, documenting the collision between civilization and the fragile habitats that sustain endangered wildlife. His films also depict the dangers that adventurers face in their wilderness journeys.

In early March Hamlin is back in Washington, D.C., editing his film, Avalanche:Surviving Tragedy, scheduled to air six weeks later on MSNBC's National Geographic UltimateExplorer. He's in the final sprint of a project that began four months earlier, and after four trips to western Canada and other trips to Utah, California and Washington, he's in the editing room at Geographic headquarters, piecing together the narrative for the hour-long documentary.

Hamlin, who comes to work in blue jeans, gray sneakers and a checked, button-down shirt, takes the raw material from 40 hours of interviews and molds it into a gripping tale that explores the risks and rewards of venturing deep into the back country.

He sits in a dimly lit room, peering through horned-rim glasses at a 4-inch-thick spiral notebook. It contains transcripts from interviews with survivors—and the kin of the victims—of two deadly snow slides in the Canadian Rockies in 2003. The avalanches killed 14, including four-time world champion snowboarder Craig Kelly.

A video editor controls the digital editing machine, where she calls up the taped interviews, pares down the statements to the essential and, with Hamlin, lays the foundation for the television movie's first of five segments, or "acts." Hamlin writes narration to link their thoughts, and at one point consults notes he scribbled on a scrap of paper by his bedside at 2 that morning. In two weeks Hamlin will layer on music and visual images to illustrate these stories, making sure the documentary is completed by April 16, just two days before it's scheduled to air.

When he's shooting on location, Hamlin says he has an idea for the story but no script to follow, so he's looking for "little treasures" of sound and image. In the editing room, he likens the process to fitting together the pieces of a complex puzzle. There's also a touch of magic as he culls out the best from the interviews and blends thoughts to drive the story and create a moving film drama. "There's a certain alchemy to all this," he says. "You hope that there's no lead there, just gold that you're transforming into shimmering gold."

The avalanche film, which examines how survivors move on with their lives after a terrible tragedy, brings Hamlin full circle to the movie he made a decade ago at the University of Southern California's Graduate School of Cinema-Television. When one survivor in the new film says she deals with the tragedy by recognizing life is short and reason enough to pursue her passions, it's a message audiences heard in Stolen Days, Hamlin's 1994 documentary shown on PBS and at film festivals around the country. That movie, which told the stories of young adults dying of cancer, wasn't the movie Hamlin envisioned when he moved to Los Angeles in 1991 to take his budding film career to the next level. The central character was Hamlin's older brother, Mark, then 36 and a father of two, who was in the final throes of lung cancer. As a heartbroken Hamlin helped care for his dying brother, he was also taking time to document Mark's final days for the film—and taking his brother's philosophy to heart: that there is no "greater joy than cherishing the immediate moment you are in."

"Making that was the hardest thing I have ever done," says Hamlin. "But that film became my documentary calling card."

Hamlin's fascination with television began during his childhood at WBZ in Boston, watching his mother, Sonya Hamlin, a talk-show host, from the pedestal of the studio cameras. His interest in documentaries was sparked by an eighth-grade teacher who, over three days one fall, showed The Battle of Algiers, the film about the bloody uprising that ended Frances colonial domination of Algeria.

"It was mind-blowing because it rang so true," says Hamlin. "It was a window into real-life experience, and showed me that documentary techniques could have incredible power."

At Dartmouth Hamlin majored in education and traveled between quarters on trips with the Ledyard Canoe Club to the waters of Idaho, Quebec and North Carolina. It took Hamlin five years to graduate because he had to schedule his courses around three offcampus terms as a Tucker Foundation fellow. One quarter he taught school in inner-city classrooms of Jersey City, New Jersey. Then he worked at the Public Media Center in San Francisco, helping nonprofit groups produce programs for local access cable channels.

His interest in television deepened during a semester at the Children's Television Workshop, helping prepare scripts for Big Bird on Sesame Street. He served as a bridge between the shows screenwriters, who were bent on creating entertaining television for kids, and the shows child psychologists, who wanted the programs to teach important values.

Working with Jim Henson's team, Hamlin saw firsthand how television could be both educational and entertaining. Those values are the twin foundations of Hamlin's work at National Geographic.

"I got into television because I saw it was a medium that could create social change and make the world a better place," says Hamlin. "It's not easy, but that's still my mission, that's why I'm still at Geographic."

After graduation Hamlin broke into television as a freelance production assistant, scrambling for work at Boston stations and production companies. When he heard in 1988 that Dan Dimancescu '64 was leading a South Korean kayak trip with the Ledyard Canoe Club, he convinced Dimancescu to let him come along, with an idea to shoot footage on spec for NBC's Olympic coverage from Seoul later that year.

NBC bought Hamlin's segments, and his first national piece aired with narration by Jane Pauley. "That gave me a reel, something to show people, and I started getting production work at Boston networks and did several pieces for NASA," he says.

After several years in Boston Hamlin grew restless, knowing that film careers were rarely built in Beantown. So in 1991, the year he was married, Hamlin headed to film school at USC.

The film about his brother gave him another reel to show around, and by 1997 Hamlin had landed a position as staff producer at National Geographic, which was branching out into cable television. Seven years later, he's the senior member on Geographies staff of producers, with his work shown both on National Geographic Channel and MSNBCs Ultimate Explorer.

Hamlin says the job sends him "on a trip of a lifetime, four times a year." That includes four journeys to Mount Everest to film climbers struggling to summit the world's highest mountain. On one climb, he reached Camp 2, at 21,500 feet. Each of those films required technical ice-climbing as well as the harrowing ascent at Everest's Khumbu Falls, inching along an aluminum ladder placed across a 150-foot-wide crevasse.

Hamlin, who considers himself "a moderate risk taker," says taking risks in the wilderness can be easier than in the editing room. "My body knows what it has to do to get from point A to point B," he says. "But taking risks in film is a much grayer area because it's not just me, there's someone else's perception of my work."

Renowned climber Pete Athans helped Hamlin shoot on Everest. "David has a very flexible approach and doesn't go in with a particular dogma," he says. "He doesn't try to drive the story, and in that sense he is a pure documentarian: He shoots the action, and tells the story in the most creative way he can."

Over the past two years Hamlin produced a 26-episode series, Reptile Wild, for the National Geographic Channel, which brought him to Venezuela's Oronoco River and the marshes of southern Sri Lanka to document the struggles of species imperiled by the march of progress into once pristine habitats. "Through these films I've come to realize that animal conservation is not a wildlife issue as much as it is an economic issue," he says. "It's the same in Venezuela and Nepal. People need to develop sustainable economies so they don't have to tear down the forests or poach wildlife to survive."

As series producer Hamlin had the chance to step back and oversee the two-year project, which cut down significantly on his travel schedule because he only did the actual shooting on a few episodes. That was a boon to Hamlin, who lives in D.C. with his wife Julie, and sons William, 4, and Evan, 7.

"The travel can be brutal and it's hard to keep up the pace," says Hamlin. "Producing the series let me stay home more, and it worked, but now the series is done. As time marches on, I'm hoping to find more opportunities that will let me stay at home and help others make the best films they can."

In the meantime, he's back pitching ideas for his next Geographic documentary in some far-flung comer of the world. High on his list are the forests of central Africa, where he shot two films with Jane Goodall to document the growing threats to wildlife there.

In 2002 Hamlin and Goodall returned to the Tanzanian nature preserve where Goodall began her research with chimpanzees 40 years ago. Many of Hamlin's films entail a search or a journey, and for Chimps in Crisis, Hamlin and Goodall set out to find Fifi, a female chimp she had first befriended in the early 19605.

It seemed like a good plot device for Goodall, his story's hero. "It was a way to put the conservation issue in context, and Jane needed to have something to do in the movie beyond saying interesting things," Hamlin says. "We needed a cathartic journey for the film, and Jane, as the protagonist, needed something to overcome."

But as time slipped away on the four-week shoot, their team still had not found the chimp. By then, Hamlin had rethought the movie and was prepared to use another theme. Then, on the last day, they found Fifi. Goodall was exultant; Hamlin had his shot, and was able to deliver the film he'd promised.

"The canvas we draw from is real, and we apply fictional constructs to make the story," says Hamlin. "But there's an underlying foundation of legitimacy that's powerful. I like being in that world, capturing something truthful."

Capturing those moments, such as Goodall's reunion with Fifi, can also be intrusive. "It's moments like that when I feel lucky to capture a moment so genuine that I know people will connect to it," he says. "But I also felt awkward to be there as I intruded on Janes private joy."

Even with the modern digital equipment, documentary filmmaking on location in the wilderness can test the most seasoned outdoorsman. During one trip to the African forest Hamlin contracted malaria, and ended up quarantined in a hospital for several days with a fever of 105. On another assignment he was onboard an old Russian biplane that had to make an emergency landing at a weather station airstrip on Mould Bay, Prince Patrick Island (population: 4). "That was seriously in the middle of nowhere," says Hamlin. "If we had gone down, we wouldn't have been found."

An accomplished skier and climber, Hamlin also narrowly avoided tragedy one afternoon in 1999 on the Pakistan mountain K2. While filming a climbing expedition at 17,000 feet, he lost his footing and started sliding toward a deep crevasse. He grabbed onto a rock to stop his descent, but his crampons got tangled, his leg locked, and Hamlin blew out the anterior cruciate ligament of his right knee. He hobbled down the mountain and was carried by stretcher to a lower altitude and airlifted to Islamabad.

He flew home, was fitted for a brace and then flew directly to Iceland the next day to stay on schedule for a movie about the volcano rappelled off a cliff, Hamlin thought back to his brother's final days. Mark would have smiled to see him there, camera in hand, his swollen knee secure in a brace, he says.

"I have taken Marks words to heart—that every day is truly a miracle," he says. "I try to treasure every day."

On Assignment Hamlin on the job (fromleft) in Tanzania withprimate specialist JaneGoodall; in Congo withpygmy children duringpart of a 15-month,1,200-mile walkthrough Central Africa;and braving the cold onCanada's Baffin Island.

THE JOB SENDS HIM ON A TRIP OF A LIFETIME FOUR TIMES A YEAR.

DAVID MCKAY WILSON, a New York-based journalist, writes abouteducation for The Journal News in White Plains, New York.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryCanoes Undying

July | August 2004 By JIM COLLINS ’84 -

Feature

FeatureUnderstanding Failure

July | August 2004 By JULIE SLOANE ’99 -

Feature

FeatureOn The Water

July | August 2004 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionTrade, Jobs and Politics

July | August 2004 By Douglas A. Irwin -

Sports

SportsYouth at Risk

July | August 2004 By Irene M. Wielawski -

Student Opinion

Student OpinionMoney Matters

July | August 2004 By Andrew Mulligan ’05

DAVID MCKAY WILSON

-

Feature

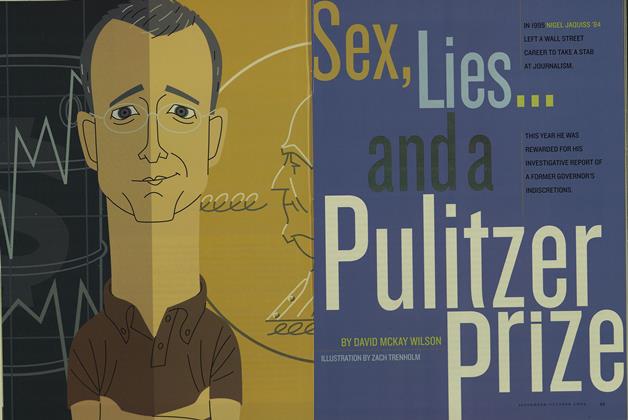

FeatureSex, Lies... and a Pulitzer Prize

Sept/Oct 2005 By DAVID MCKAY WILSON -

Cover Story

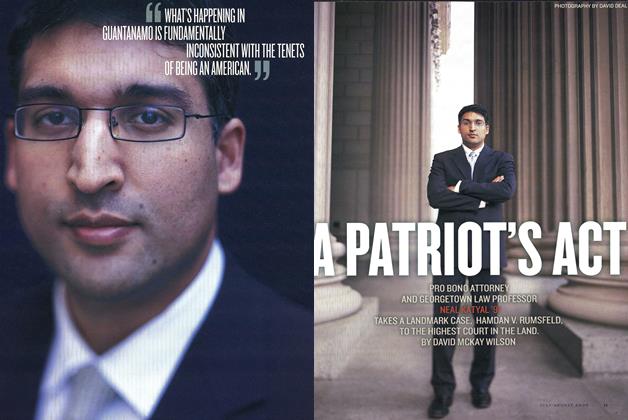

Cover StoryA Patriot’s Act

July/August 2006 By DAVID MCKAY WILSON -

INTERVIEW

INTERVIEW“A Huge Story”

Sept/Oct 2008 By DAVID MCKAY WILSON -

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDESea Change

Jan/Feb 2009 By David McKay Wilson -

Feature

FeatureCampbell’s Coup

Jan/Feb 2010 By DAVID MCKAY WILSON -

Sports

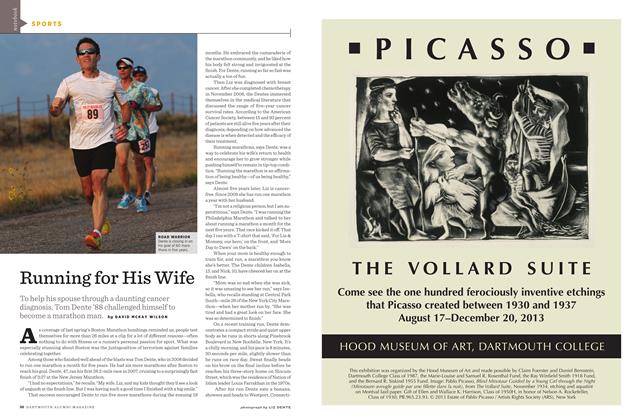

SportsRunning for His Wife

September | October 2013 By DAVID MCKAY WILSON

Features

-

Feature

FeatureArtists

March 1977 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO HUCKTHE DISC

Sept/Oct 2001 By ERIC ZASLOW '89 -

Feature

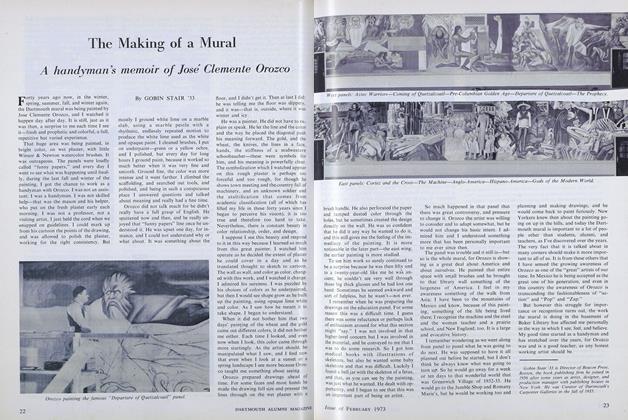

FeatureThe Making of a Mural

FEBRUARY 1973 By GOBIN STAIR '33 -

Feature

FeaturePROBLEM SOLVER

SEPTEMBER 1990 By John Aronsohn '90 -

Feature

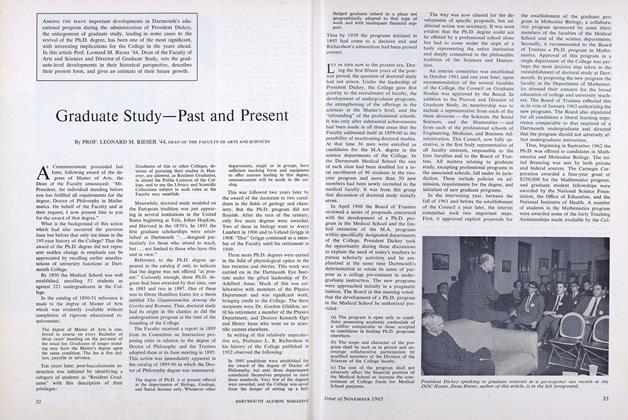

FeatureGraduate Study—Past and Present

NOVEMBER 1965 By PROF. LEONARD M. RIESER '44 -

Feature

FeatureADMISSIONS—SCHOLARSHIPS—ENROLLMENT

April 1954 By Robert L. Allen '45