AN EDUCATION EXPERT WEIGHS IN ON INFLATION, STUDY HABITS AND THE CORRELATION BETWEEN COLLEGE AND CAREER SUCCESS.

THE LATEST EVIDENCE THAT inflation is a big-time issue comes from "The Ethicist," Randy Cohen's regular column in The New York Times Magazine. Last October an anguished professor in Cambridge who had discovered that he was giving grades siderably below his departmental average asked Cohen whether he should raise his grades to fall in line, even though that would contribute to grade inflation.

The Ethicist avoided giving him a straight answer but endorsed a policy of letting everyone know the grading patterns, on the assumption that parency" would shame the "hyper-inflationary" graders into better behavior. (On the contrary, it would probably attract students into their courses!)

I've interviewed a number of student- on this issue recently (purposely avoiding Dartmouth to avoid conflict of interest). Here's what I found: Matt Mindrum of Indiana University says he studied a total of eight hours for his four semester exams, while parvin Sathe of NYU says he studied for 20 hours. Marc Hubbard of Colgate reports putting in about 60 hours, but another Colgate student, Bonnie Vanzler, says she studied for just 12. All four made the dean's list at their respective institutions.

These days it seems as if nearly everyone in college is receiving A's, making the dean's list or with honors. What's more interesting is that college students in general are spending fewer hours studing, while taking more remedial courses and fewer courses in mathematics, history, English and foreign languages. According to the National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE), students report that they average only 10 to 15 hours of academic work outside if class per week and are able to attain B of better grade-point averages.

If today's college students were smarter or better prepared, that would explain the Higher grades, but that doesn't seem to be the case. Over the last 30 years SAT scores of entering students have declined, and fully one-third of entering freshmen are enrolled in at least one remedial reading, writing or mathematics course, the Highest enrollment being in math. According to Lynn Steen, a mathematics professor at St. Olaf College, 80 percent of all student work in college math is remedial.

If they're not smarter or better prepared, perhaps they're working harder? Not! George Kuh of NSSE says that students get higher grades for less effort because of an unspoken agreement between professors and their students: "If you don't hassle me, I won't ask too much of you." Kuh is sympathelic to the plight of many college instructors, who often are responsible for teaching hundreds of students: "College teachers have too many students and not enough time, So it's easier to give goodgrades rather than have to explain to an angry student how a grade was arruved at."

So how do students get all those A's without working particularly hard? Easy, they go where the A's are. And they're not enrolling in classes that once were considered essential to good citizenship. A 1995 study of transcripts by U.S. Department of Education revealed that 26 percent took no history courses, 30 percent took no math, 39 percent took no English or American literature and 59 percent took no foreign language.

And where are the easy A's? Duke Professor Valen E. JohnSon is the author of CollegeGrading: A National Crisis in Undergraduate Education. He studied 42,000 grade reports and discovered that the easier grades were to be found in the "soft" sciences such as music, cultural anthropology, sociology, psychology, communications and other so- called "practical arts" courses. The hardest A's to earn were in the natural sciences such as physics. Johnson found a difference of nearly one letter grade between the easiest department (music, With a mean grade of 3.69) and the toughest (math, with a mean of 2.91).

Ending grade inflation isn't a magic bullet, but colleges and universities have fa obligation to defend intellectual integrity. At the same time, someone ought to tell students how unimportant good grades are once they leave the campus.

Grade-obsessed Students probably assume that high grades lead to better jobs and more money, things they care about. In 1993, 57 percent of students said that the chief benefit of a college education is increased earning power, and that number has been going up. Thirty-seven percent of students say they'd drop out of College if they didn't think they were helping their job chances.

What is correlated with success is what is called "engagement," genuine involvement in courses and campus activities. Engagement leads to what's called "deep learning," or learning for understanding. That's Very different from just memorizing stuff for the exam and then forgetting it. AsRuss Edgerton of the Pew Forum on Undergraduate Learning notes: "What countsmost is what students do in college, notwho they are, or where they go to College, or what their grades are."

JOHN'MERROW '63, a former teacher, hasbeen reporting about educationfor NPR and PBSsince 1974. He is the author of Choosing Excellence (The Scarecrow Press) and received theGeorge Foster Peabody Award in 2001

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryA is for Abundance

March | April 2004 By RICK GREEN -

Feature

FeatureA Day in the Life

March | April 2004 By JONI COLE, MALS ’95 -

Feature

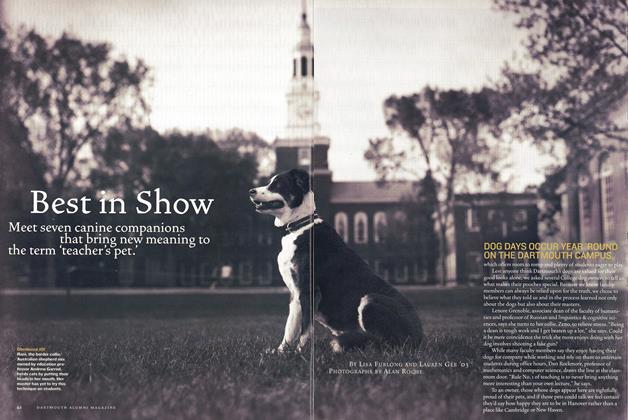

FeatureBest in Show

March | April 2004 By Lisa Furlong and Lauren Gee ’03 -

Article

ArticleSeen & Heard

March | April 2004 By MIKE MAHONEY '92 -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionSaturate, Don’t Isolate

March | April 2004 By David C. Kang -

From the Dean

From the DeanThe Fourth ‘R’

March | April 2004 By Michael S. Gazzaniga ’61