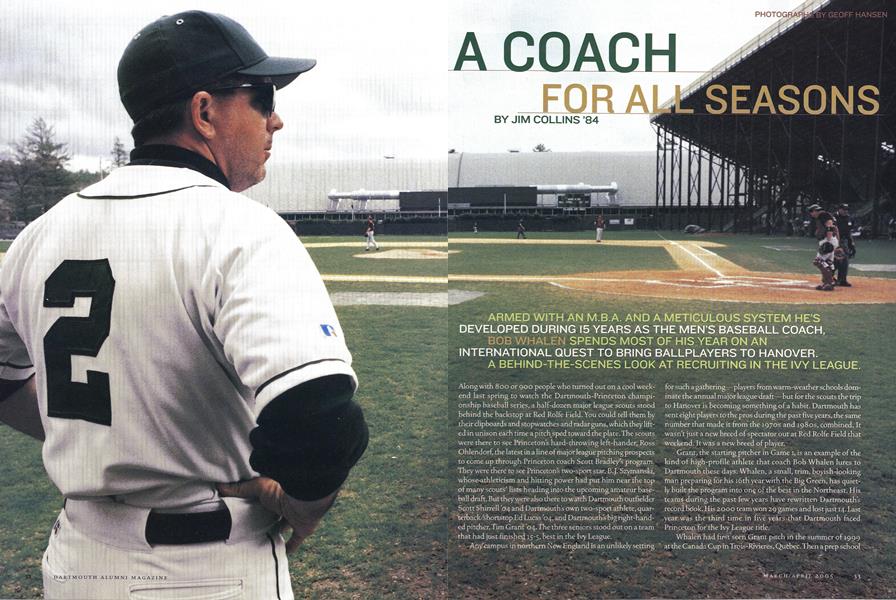

A Coach For All Seasons

Armed with an M.B.A. and a meticulous system he’s developed during 15 years as the men’s baseball coach, Bob Whalen spends most of his year on an international quest to bring ballplayers to Hanover. A behind-the-scenes look at recruiting in the Ivy League.

Mar/Apr 2005 JIM COLLINS ’84Armed with an M.B.A. and a meticulous system he’s developed during 15 years as the men’s baseball coach, Bob Whalen spends most of his year on an international quest to bring ballplayers to Hanover. A behind-the-scenes look at recruiting in the Ivy League.

Mar/Apr 2005 JIM COLLINS ’84ARMED WITH AN M.B.A. AND A METICULOUS SYSTEM HE'S DEVELOPED DURING !5 YEARS AS THE MEN'S BASEBALL COACH, SPENDS MOST OF HIS YEAR ON AN INTERNATIONAL QUEST TO BRING BALLPLAYERS TO HANOVER, A BEHIND-THE-SCENES LOOK AT RECRUITING IN THE IVY LEAGUE.

Along with 800 or 900 people who turned out on a cool weekend last spring to watch the Dartmouth-Princeton championship baseball series, a half-dozen major league scouts stood behind the backstop at Red Rolfe Field. You could tell them by their clipboards and stopwatches and radar guns, which they lifted in unison each time a pitch sped toward the plate. The scouts were there to see Princeton's hard-throwing left-hander, Ross Ohlendorf, the latest in a line of major league pitching prospects to come up through Princeton coach Scott Bradley's program.

They were there to see Princetons two-sport star, B.J. Szymamki, whose-athleficism and hitting power had put him. near the top of jxiany sco-uts" lists heading into the upcoming amateur baseball draft. But they were also there to watch Dartmouth outfielder Scott Shirrell '04 and Dartmouth's own two-sport athlete, quar" terback/sh ortstop Ed Lucas '04, and Dartmouth's big right-hand- ed pitcher, Tim Grant '04,"the three seniors stood out on a team hat had just finished 15-5, best in the Ivy League.

Any campus in northern New England is an unlikely setting for such a gathering- players from warm-weather schools inate the annual major league draft -but for the scouts the trip to Hanover is becoming something of a habit. Dartmouth has sent eight players to the prosduring the past five years, the same number that made it from the 1970s and 1980s, combined. It wasn't just a new breed of spectator out at Red Rolfe Field that weekend. It was a new breed of player.

Grant, the starting pitcher in Game 1, is an. example of the kind of high-profile athlete that coach Bob Whalen lures to Dartmouth these days. Whalen, a small, trim, boyish-looking man preparing for his 16th year with the Big Green, has quietly built the program into one of the best in the Northeast. His teams during the past few years have rewritten Dartmouth's record book. His 2000 team won 29 games and lost just 14. Last year was thethird time in five years that Dartmouth faced Princeton for the Ivy League title.

junior, Grant front-lined a select team from British Columbia. Whalen, whose father had been the scouting director for the major league Pittsburgh Pirates ("I grew up with player evaluations all around the house," he says), had been tipped off by an old family acquaintance about the young pitcher from Vancouver who fit Whalen's narrow profile: a Division I talent with a strong academic background and a family devoted to education.

Whalen had taken a chance driving into eastern Canada. His recruiting budget of $30,000 is less than half that of big scholarship schools, and it has to cover everything from the coaches' travel expenses to the teams media guide and bringing athletes to Hanover for campus visits. With limited resources, Whalen faces the daunting challenge of identifying six or eight high-caliber baseball players each year who not only can get into Dartmouth, but who will choose Dartmouth over all other suitors. He can't afford to be wrong on many. The athletic department limits him to a "target number" of names he can pass along to the admissions office, a number that varies each year with different needs among Dartmouth's extraordinarily high number of 34 varsity programs. Each year Whalen's target number nearly matches the number of kids he needs to fill out his roster. His recruits, ranked by priority, get an extra hard look and benefit of the doubt from the admissions office, but they are by no means guaranteed.

Unlike at many Division I colleges, Dartmouth's admissions office has complete autonomy in admitting students. And the Ivy League monitors its admission process more closely than any other conference in the country. Ivy schools require their athletes to be representative of their student bodies as a whole. To that end, administrators have created a complicated measure called the "academic index," based in part on SAT scores, high school grades and class rank. A class of admitted recruits (about 200 athletes each year at Dartmouth) has to fall within one standard deviation of the overall student body's academic index. Social scientists have de- termined that within that deviation, a particular group is consid- ered part of a population rather than a separate population altogether. At Dartmouth the goal is to make sure that incoming athletes have a place in the academic community that the College values so highly. As Dartmouth's admissions process has grown increasingly competitive during the past several years, Whalen's chal- lenge has grown increasingly difficult.

HE HAS A BROADER VIEW of the world than most college baseball coaches. He earned an M.B.A. in finance in 1986 from the University of Maine, just in case a career in baseball didn't sustain him. (He'd been an infielder as an undergraduate at Maine in the late 1970s but wasn't good enough to turn playing into a career; coaching, however, fueled his passion for the game.) He's come to look at recruiting as he does investing, weighing the risks against potential pay-offs. His success, he figures, depends on two factors: casting a huge net and being brutally efficient. "Hey, we're not smarter than anybody else doing this," Whalen insists. "But I look at the resources and challenges here, and I know we better have some kind of plan." Putting his M.B.A. training to use, Whalen cross-references data from the Dartmouth admissions office with Ivy League baseball rosters, the geographic areas where the best amateur baseball is played, and Dartmouth's football roster. (He has found a correlation. Back when he started, most of Dartmouth's remaining two-sport athletes, such as Lucas, were baseball/football.) Updating his analysis every four years, he identifies the 25 or 26 states that are most likely to produce Dartmouth baseball players and focuses his recruiting efforts there.

Each year Whalen mails letters to the baseball coaches at every high school in the states on his list. The initial letter introduces Dartmouth and asks for names of good students who can really play, who are legitimate Division I athletes. The responses help build an annual database of some 1,500 prospects on Whalen's computer. "That's where we start," says Whalen. "But this isn't swimming or golf or track. In baseball you can't look at times or scores and know for sure a kid can compete at this level. That's when it comes down to rolling your sleeves up and getting out there." He and assistant coach Tony Baldwin are out there virtually every week and weekend during the summer, taking in more than 125 games each, almost all of them in the Mid-Atlantic, New England and high-SAT regions of California's Bay Area, Orange County and greater San Diego. Deputy athletic director Bob Ceplikas '78 refers to the coaches, admiringly, as "road warriors."

"Back in 1992 we were the only Ivy baseball program on the ground looking at players in California," says Whalen. "We realized that a lot of people in California are originally from the East. They put a high value on education and they're aware of what Dartmouth is all about. In the South, where people have been living for five generations, Dartmouth is much less a known quantity and a much harder sell." He's continually re-jigging the net. California, for instance, is no longer underdeveloped territory. In recent years California has become the top-producing state for both Ivy League baseball and football players. A third of Dartmouth's baseball roster is West Coast. And all of the Ivy baseball coaches know it. Whalen has added the affluent suburbs around Chicago to his focus, and he's recently been experimenting with select zip codes in Texas, trying to stay ahead of the curve.

Whalen's system demands hard work, but it has paid off. An extraordinarily high percentage of his targeted athletes—more than half, in recent years—have been admitted by early admission, nearly twice the rate that a typical coach at Dartmouth might expect. In 1999 British Columbia wasn't part of Whalens net. It was a gamble driving to Trois-Rivieres to watch Grant pitch. But Whalen trusted his instincts. He watched Grant throw on a back field, then in competition, and knew he'd found a good one. Whalen had made contact with Grant only a month earlier.(The NCAAforbids a coach from initiating personal contact with recruited players until the July following the players junior year.) But he had done everything he could to start a relationship before that. He had sent along general information about Dartmouth to Grant s parents, asked for academic transcripts, encouraged them to fill out the Colleges online financial data sheet. He made his interest clear. During the coming months Whalen established a strong rapport with both Grant and his family, first by mail and then through long telephone conversations. Grants parents, both involved in business, were respectful but cautious—they were encouraging Tim to consider Harvard, wanted to make sure Dartmouth felt like a good fit, wanted to be assured that their son wouldn't be giving up a chance to play baseball professionally.

For his part, Whalen approached his pitch systematically: Sell the Ivy League as an academic product first, then differentiate Dartmouth from others in the league. He gave the process time, to let the parents assimilate the information, to get comfortable with the idea. Then he pitched the people, then the program. "We try to take a business approach to what we're selling," he says. "But in the end, parents want to know that their kid is going to a place where he'll be nurtured, where the values are in order."

Grant and his parents eventually bought into Whalen's vision: Tim could come to a world-class academic institution, be surrounded by a group of highly motivated athletes, and still prepare for a career in professional baseball. That was Whalen's message, over and over: "We want kids who want to excel in school and baseball, No. 1 and IA," he told them. Come to Dartmouth and be challenged by the environment. See how the rigors of an Ivy League athletic program can foster strengths of character and life skills. Reach as high as you can academically and athletically. It's no simple task to sell the vision. Dartmouth's baseball team hasn't been a Division I power since its College World Series team of 1970. It hasn't made the NCAA tournament since 1987, when future major league all-star Mike Remlinger '88 carried the Big Green to a first-round win over Michigan. And the overall strength of the Ivy League, according to Baseball America, ranks near the bottom of the 30 Division I conferences. In addition to the absence of athletic scholarships, the low baseball profile, the high academic demands and facilities that can't touch the lavish, minor league-quality complexes of many big programs, Dartmouth and the other Ivy schools have to compete under a restrictive set of conference guidelines that limit everything from out-of-seas on practices to the number of dates—20—a team is allowed to play games in the spring.

Whalens program, without the rich corporate sponsorships and athletic budgets of a Duke or Stanford, relies on alumni groups for a significant part of its operating money. (The Friends of Dart- mouth Baseball group provides a third of Whalens recruiting bud- get, for instance, and helps fund the team's annual spring trip and the salary of one of Whalens two assistant coaches. In 2003-04 the Dartmouth Athletic Sponsor Program raised more than $300,000 to cover the cost of bringing recruited athletes to Dartmouth for campus visits, some $5,600 of which went to the baseball program.) Long, snowy winters, which often keep teams indoors until early or mid-April, are harsh throughout the north but they're particularly challenging in Hanover, New Hampshire. Even so, says Mike Levy '0l, "North Carolina, Stanford, Northwestern and Tulane all recruited me. I didn't fall in love with the feel of the team or the baseball environment at any of them like I did at Dartmouth—Dartmouth had the tightest-knit group of guys, by far." Levy, after a stellar college career, was drafted by the St. Louis Cardinals. He continues to be in touch with the world of high- level athletes as an account executive for Host Communications, a specialty marketing firm in Atlanta—and continues to keep in touch with Whalen, as do many former Dartmouth players.

Within the Ivy League, Dartmouth has to overcome the deeper reputations and name recognition of Yale, Harvard and, in the case of Princeton, a head coach who is a former major leaguer. "Some of the guys on our team grew up with Scott Bradley posters on our walls. It's tough to compete against that," says Brian Nickerson '01, who played for a time in the Dodgers organization before becoming a manager in a Chicago-based office supply company.

The game has changed. Gone are the days of walk-ons at Red Rolfe Field, as are the days when two- and three-sport letter winners were common and 90 percent of the Big Green baseball roster came out of New England. Whalen continues to hold open try- outs each fall, but they're mostly for public relations and the chance to pick up a body or two for fall scrimmages to replace the regular players who are off-campus that term. The freshman team was dropped in the early 19705, the JV program in the early 19905. In line with a national trend across all college sports, Dartmouth's baseball program has become specialized, dependent on recruited single-sport athletes who can step onto the field and compete as freshmen. Typically, Whalen's 28-man roster includes only a couple of nonrecruited players, and they are usually "recruited walkons"—players whom Whalen has identified and encouraged to come to Dartmouth, but who haven't benefited from his support in the admissions process.

Fortunately" for Dartmouth, Whalen knows more than a thing or two about identifying young talent. At Maine he was a part of five College World Series teams, once as a player and four times as an assistant coach. As a coach there he worked with more than 2 o future pros. He learned what it takes to sell a recruit on a New England school, learned how crucial the success of a program is in selling itself. Prior to last year's championship series with Princeton, 10 of his players at Dartmouth had gone pro, including his first captain, Mark Johnson '90, who went on to play in the majors with the Pittsburgh Pirates and New York Mets.

Unlike Dartmouth's admissions office, which is hyper-aware of how Dartmouth fares head-to-head against other institutions, Whalen doesn't track the schools he loses recruits to. A desire to go to Dartmouth is one of his early weeding-out criteria, one that does more than any other to narrow his field and reduce his risk. By the time Whalen submits his list of candidates to the admissions office, few of his recruits are seriously considering other schools. The schools he mentions as chief competitors, though—Princeton, Harvard, Stanford, Vanderbilt—speak volumes about where Dartmouth's program stands.

At least one trend is working in Whalen's favor. It reflects the changing demographics of the national pastime. Most top baseball players from America and Canada come not from rural or urban areas but from suburban places—places where values typically include an emphasis on higher education. In that respect, Dartmouth's pool of baseball prospects has deepened during the past generation. And that pool is savvy. Prospects—and their parents—know the colleges where drafted players come from, know the schools that send players to elite summer leagues such as the Cape Cod Baseball League in Massachusetts. Recruits know they'll be seen by scouts at Dartmouth. And whether or not they turn pro, the players know they'll have a diploma that means something at the end of four years.

Whalen's early contact with Tim Grant that junior summer turned out to be crucial. During the next year Grant emerged as one of the best schoolboy pitchers in Canada. As a high school senior he pitched for the Canadian Junior National team, toured across Canada and appeared in showcases at Toronto's Sky Dome and at the Seattle Mariners' spring training complex in Arizona, impressing major league scouts. He grew to and 170 pounds, and threw a two- and four-seam fastball 85 to 87 miles per hour. By the time the Notre Dames and Pepperdines started calling, Grant had long since applied to and been accepted to Dartmouth, by early decision. His recruiting visit to Hanover on a glorious weekend in the fall of 1999 was the only campus trip his family made—any- where—and the only one he needed.

AT TEN O'CLOCK on a Monday morning in Jan- uary 2004, four months before pitching in lastyear s championship series against Princeton, Grant, a se- nior co-captain, joined Whalen and two other pitch- ers in Leverone Field House for an hour of throwing drills and "long-toss," an exercise pitchers do to strengthen their arms and reinforce good mechanics. It was a far cry from what the other top-flight prospects across the country were doing at the time, but it revealed much about the program Grant had come to love. A dusting of powdery snow had fallen overnight; it swirled outside Leverone's smokedglass windows on a bitter, bright, 12-degree day. Inside the air was cool and smelled of rubber and sweat. The sharp, resonant crack of a hard leather ball hitting a leather glove echoed through the mostly empty field house. Whalen, in a Dartmouth ball cap, gray T-shirt and jeans, stood alertly, watching his pitchers, stopping them occasionally to point out flaws in a delivery or demonstrate different "release points." He was direct and clear and positive, something Grant and the other players appreciated. A pitching recruit from Michigan sat nearby with his father on a pole-vaulting mat, observing. "This is awesome," he said. "It's so personal here."

Grant, taller than the pitchers with him, deeper across the chest, had added an inch and 30 pounds since Whalen watched him pitch in Quebec. He'd also added 3 or 4 m.p.h to his sinking fastball, which now reached better than 90 miles an hour. He was wearing a gray Dartmouth practice shirt and blue mesh gym shorts bearing the Cape Cod Baseball League 'insignia, a mark of the country's best summer showcase league and a prize trophy for an Ivy League player. He was carrying a 3.2 GPA in his economics major.

Grant talks about how tight the Dartmouth baseball team is, how strong its team orientation, about the skills of self-discipline and leadership he's needed to learn. "I have to say," he says, "that I see a lot of positive qualities in the players here that I didn't see in most of the guys on Cape Cod."

AS IT HAPPENED, Princeton's Ross ohlendorf outpitched Grant in the opening game of the championship series, and Princeton won again in extra innings in Game 2, claiming its fourth Ivy championship in the past five years. "Dartmouth had the best team in the league this year," said the Princeton coach after the game. "We were just lucky enough to have the best team on the field today."

The following month Grantwas drafted by the San Francisco Giants, following teammate Ed Lucas '04, picked in an early round by the Kansas City Royals. The draft brought to 12 the number of Whalen's players who have been given a shot at turning pro after playing at Dartmouth. Mean- while, sophomore Josh Faiola '06 was getting ready to pitch in the Cape Cod League. Freshman pitcher Stephen Perry '07 was named Ivy Freshman Player of the Year and given a spot on the Louisville Slugger Freshman All-America Team, the only Ivy player among the 73 players chosen.

Whalen had little time to savor the successes. His database for incoming recruits had swollen to 1,800 names, and it was time to get to work.

BOB WHALEN

"WE WANT KIDS WHO WANT TO EXCEL IN SCHOOL AND BASEBALL, NO. 1 AND 1A."

WHALEN HAS COME TO LOOK AT RECRUITING AS HE DOES INVESTING, WEIGHING THE RISKS AGAINST POTENTIAL PAY-OFFS

Since 1950 25 Dartmouth baseball players have played professional baseball. Here's the list.Peter Burnside '52Arthur Quirk '59Clark Griffith '63 Sandy Aiderson '69 Chuck Scclbach '70 Pete Broberg '72 Jim Beattie '76 Roberto Balaguer '83 Mark Mitchell '87 Tom DeMerit '88 Mike Remlinger '88 Dave Hammond '89 Mark Johnson '90 Brad Ausmus '91 Tim Carey '92 Bob Bennett '93 Joe Tosope '93 Conor Brooks '00 James Little '00 Jeff Dutremble '01 Mike Levy '01 Brian Nickerson '01 John Veiosky 02 Ed Lucas '04 Tim Grant '04

JIM COLLINS is the author of The Last Best League (Da Capo), which chronicles a season of the Cape CodLeague. He lives in Orange, New Hampshire.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

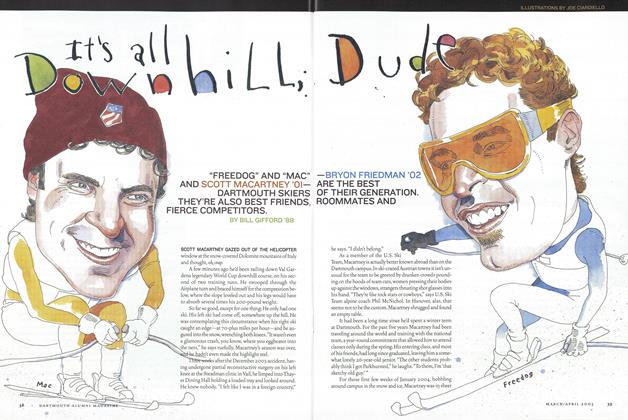

FeatureIt’s All Downhill, Dude

March | April 2005 By BILL GIFFORD ’88 -

Feature

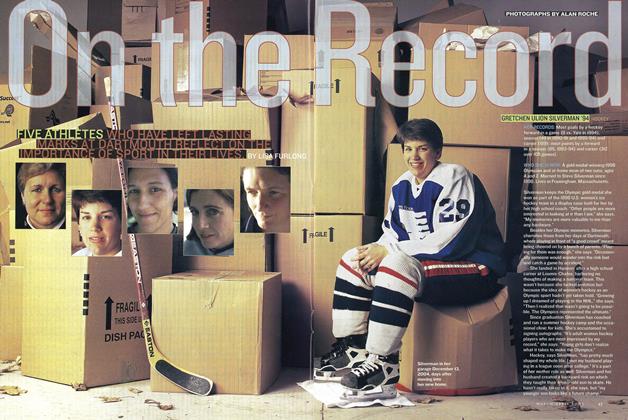

FeatureOn the Record

March | April 2005 By LISA FURLONG -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

March | April 2005 By THOMAS AMES JR. '74 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

March | April 2005 By Gray Mercer '83 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYOut of Control

March | April 2005 By Lance Roberts ’66 -

NEWS ANALYSIS

NEWS ANALYSISFraming the Letter

March | April 2005 By Brad Parks ’96

JIM COLLINS ’84

-

Feature

FeatureThe Daredevil

Jan/Feb 2013 By JIM COLLINS ’84 -

COVER STORY

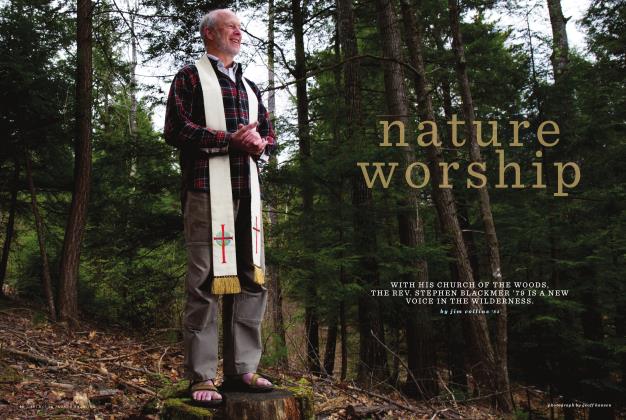

COVER STORYNature Worship

MAY | JUNE 2019 By jim collins ’84 -

PURSUITS

PURSUITSPuck Promoter

JULY | AUGUST 2020 By Jim Collins ’84 -

Features

FeaturesEveryday Zen

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2024 By JIM COLLINS ’84 -

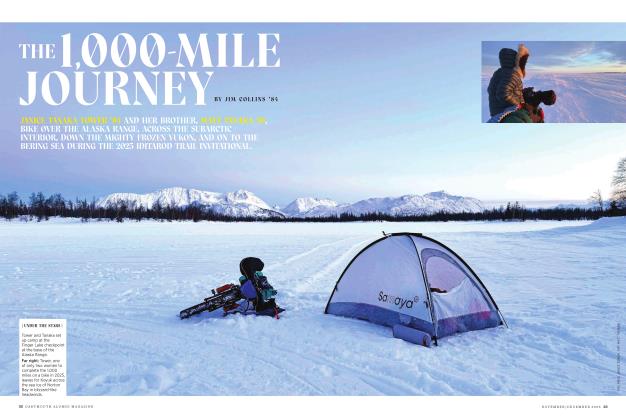

The 1,000-mile Journey

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2025 By JIM COLLINS ’84 -

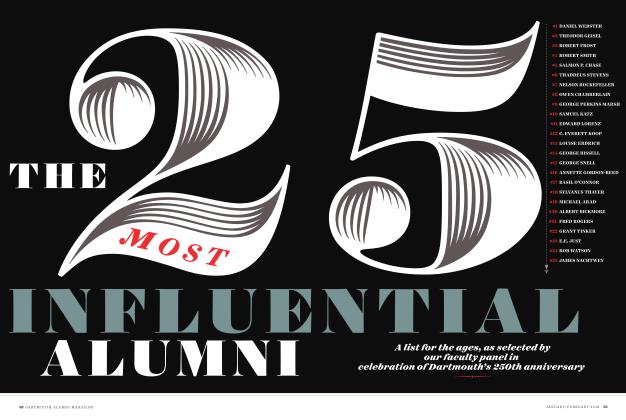

The 25 Most Influential Alumni

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2019 By Rick Beyer ’78, George M. Spencer, Jim Collins ’84, 3 more ...