An Open Door Policy

In the wake of a complaint by students with disabilities two decades ago, Dartmouth now accommodates students with a broad range of special needs.

July/August 2006 Irene M. WielawskiIn the wake of a complaint by students with disabilities two decades ago, Dartmouth now accommodates students with a broad range of special needs.

July/August 2006 Irene M. WielawskiIn the wake of a complaint by students with disabilities two decades ago, Dartmouth now accommodates students with a broad range of special needs.

At the start of every academic term at dartmouth, a letter titled "Accommodating Dartmouth Students with Disabilities" routinely lands in faculty mailboxes.

The letter, this year from Dean of the Faculty Carol Folt and Dean of the College James Larimore, runs a little over two pages and details the services and accommodations to which the more than 250 students with disabilities at Dartmouth are entitled under the federal Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990 and the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. Some students need extra time on tests. Others qualify for technological assistance such as computer software that converts speech into typed notes. Still others need personal assistants in the classroom—note-takers, perhaps, or an interpreter who can translate a professors lecture into sign language.

What's remarkable is that such accommodations are considered routine today at Dartmouth. Professors typically make an announcement on the first day of class, inviting students with physical, learning, medical and psychiatric disorders to let them know of any special needs. The range of conditions includes mobility, hearing and vision problems, neurologically based information processing disorders such as dyslexia, and serious chronic illnesses such as diabetes, cancer and depression. The faculty works closely with staff at the office of disabilities services to adjust teaching plans and determine if individual students need equipment or other assistance.

It was not always so.

Two decades ago the College came under the scrutiny of the U.S. Department of Education for possible violations of civil rights of students with disabilities. Triggered by a small group of students who filed a complaint alleging inconsistent and discriminatory practices by professors, the investigation was a searing experience for many of those involved, not the least for Shelley Mosley Stanzel '86 (see sidebar, page 41), the only named complainant. For many years Stanzel, now an entrepreneur in Dallas, kept clippings from The Dartmouth and other newspapers to memorialize what she calls "the vitriol" of administrator reluctant to acknowledge the needs of students with socalled invisible disabilities—neurological, psychiatric and medical conditions no less handicapping to the pursuit of education than a flight of stairs to someone in a wheelchair.

In fact, several administrators had been quietly working on a system to identify and assist Dartmouth students with learning disabilities such as Stanzel. The federal investigation in 1985-1986 brought these efforts into the open and helped spur campus-wide discussion. The complaint was withdrawn before any determination of findings, and the College issued a statement explaining how it would comply with applicable federal laws and regulations regarding accommodation for students with disabilities.

Dartmouth has come a long way since.

Nancy Pompian, the Colleges first disabilities services coordinator rose over a 24-year tenure at Dartmouth to become a nationally recognized leader in the field of disabilities accommodation in higher education. Her successor, Cathy Trueba, recruited last fall from the University of Wisconsin following Pompian's retirement, already is taking steps to integrate the work of the disabilities office with Dartmouth's Blitzmail and Internet-learning environment.The goal is to influence the next generation of electronic communication technology, avision that goes beyond the needs of Dartmouth's students with disabilities. Trueba sees potential application in business and industry as well as home-based communication systems. "If we don't build curb cuts and ramps in the electronic architecture, we're going to have barriers in the future to everything from shopping online to participating in a teleconference on global pandemics," says Trueba. An example of user-friendly technology would be the captioning included in Dartmouth's Web casts and podcasts.

The broader applicability of what might have originated to benefit a small minority of students helps reduce the stigma of disability, say professionals in the disabilities field. After all, none of us is perfect, and we're all vulnerable to needing assistance at some point in our lives. This larger purpose complements a rich history in the United States of removing barriers to higher education, beginning with President Abraham Lincoln's authorization in 1864 of the National Deaf Mute College, later renamed Gallaudet University. The federal government acted again in 1917, passing the Vocational Education Act, and in 1945 to facilitate college enrollment for veterans returning from World War II with crippling injuries. Improved scientific understanding of the neurology of learning disabilities helped bring students with these disorders under the protection of disability laws. The civil rights and women's rights movements of the 1960s and 1970s helped by fostering greater tolerance for diversity on college campuses, according to Richard Harris, emeritus director of disabilities services at Ball State University and an historian of the field. Yet for all the progress at Dartmouth and elsewhere, disabilities accommodation remains a work in progress. The field is challenged by resource limitations as the definition of disability expands. The more recently included disabilities—psychiatric illness, for example—often require highly individualized accommodation, defying one-size-fits-all measures such as elevators or computer software. Disabilities services coordinators such as Trueba work closely with students, faculty, housing administrators, health services staff and others to meet the federal mandate of "reasonable accommodation." But it's often a judgment call, with no guarantee of success. Even with accommodation, some students simply can't make the grade.

"My job is to ensure that every student has a chance to run the same race," says Trueba. "And it's never just the office of disabilities that makes the difference. It's faculty, administrators, the student, lots of people coming together."

WHAT CONSTITUTES ACCOMMODATION OF DISABILITY? IT can be something as minor as asking a professor to face the class when speaking so a student with hearing loss can lip read or as major as giving students extra time on tests or waivers from certain graduation requirements.

Alison L. May '97 says accommodation helped make it possible for her to graduate with honors in psychology. Like Stanzel, she has a learning disability known as auditory processing, which makes it difficult to absorb information solely by hearing it in a lecture or class discussion. Students with this learning issue may be highly intelligent and capable in other respects, but their ability to learn new material depends upon also being able to read it. This is a particular issue at Dartmouth for certain students because of the way foreign language-a graduation requirement—is taught. The Rassias method, developed by French professor John Rassias, is based upon fast-paced daily drills in which students learn almost entirely by hearing the language. Trueba and others say that many students with previously undiagnosed auditory processing disorders are identified at Dartmouth by their poor performance in language courses.

Mays disability, however, was noticed long before she got to college. "It was clear in kindergarten that something was wrong," she recalls. "I would just miss things or misunderstand things. I could capture the sound signal and identify the number of syllables and maybe every fourth word, and I'd work from that to deduce the speaker's meaning."

May's parents resisted the elementary school's effort to move their daughter out of the educational mainstream. With their encouragement, May says she simply worked hard to compile the academic record necessary to win admission to Dartmouth. She arrived in Hanover confident that diligence would see her through college, too, but Dartmouth's heavy workload defeated that strategy. May's first-term grades were disappointing, leading her to the disabilities services office, where staff suggested various compensating techniques and also arranged accommodation with her professors. The latter included exams given separately from the rest of the class because, says May, "even a stray cough would destroy whatever train of thought I had going."

During class May relied heavily on what, at the time, was newly developed laptop computer technology that greatly improved her note-taking speed. She would then review the notes to absorb the information by reading, and made use of e-mail when she needed clarification from professors.

"I realize that I was extremely privileged," says May, who, inspired by the help she got at Dartmouth, is the student support services coordinator at Oakton Community College in Skokie, Illinois, where she works not only with students with disabilities but also with students needing academic assistance.

The laptop and Internet tools so helpful to May in the mid-1990s today continue to drive innovation in disabilities accommodation.

For example, Kristen A. Wong '06, who has profound hearing loss, uses a laptop with specialized software and amplifying devices to augment her own lip-reading skills. A personal assistant sets up the devices—including a wireless microphone worn by the professor in each of Wongs classes. The amplified sound feeds through Wong's laptop computer via a wireless phone link to a commercial captioning service. The captioner, who maybe located anywhere in the world, listens to the professors lecture and class discussion and types verbatim notes that rapidly appear on Wongs computer screen. It's a tremendous help, says Wong, who has benefited from marked improvements in technology and services during her time at Dartmouth. Yet she and others emphasize that neither curricular accommodation nor technology can entirely compensate for disability; hard work remains the key to academic success.

"As impressive as it is, the technology isn't perfect," says Wong, a religion major. "With captioning, because it's done phonetically, there are a lot of errors, especially in classes with a high level of jargon. So I have to not only read but also translate. That means I'm always behind in getting the information. The effort I make to keep up may not be visible because I've lived with hearing loss for a long time, but I am working very hard and concentrating all the time."

No one disputes that technology has opened up access to higher education for students with disabilities as never before. Like technological innovation in medicine, however, which has been blamed for skyrocketing health care costs, technology to assist students with disabilities is expensive and susceptible to being quickly outdated by the next innovation. This presents additional challenges to Dartmouth's disabilities services staff, which must keep current on appropriate technology for individual students while finding the means to pay for them.

Administrators declined to discuss the cost of these services. "Dartmouth is committed to providing the accommodations that students need to succeed at Dartmouth and we are quite mindful of our obligations under the law," says Larimore.

DARTMOUTH'S OFFICE OF Disabilities services is located on the third floor of Collis in a rabbit warren of offices that also houses the academic skills center. You know you're there by the poster collage in the reception area featuring great achievers with disabilities. Among them are the composer Ludwigvon Beethoven, who had progressive hearing loss and was deaf by the end of his career; the poet John Milton, who was blind; and physicist Albert Einstein, inventor Thomas Edison and actress Whoopi Goldberg, all of whom coped with learning disabilities.

Carl P. Thum, long-time director of the academic skills center, which oversees the disabilities services office, says he occasionally encounters faculty, administrators, alumni and others who are skeptical of the work of his department. They contend, says Thum, that students who need extra help don't belong at an academically rigorous college such as Dartmouth. Thum says he replies with reams of evidence that learning and other disabilities have nothing to do with intelligence, and a genial reminder of the laws that mandate accommodation for persons with disabilities.

Probably the most famous of Dartmouth's learning disabled graduates is the late Nelson A. Rockefeller '30, who had dyslexia, in which the brain visually mixes up numbers, letters and even words within a sentence. Rockefeller couldn't spell and had great difficulty reading throughout his life. Yet he managed to compile an academic record at Dartmouth that resulted in election to Phi Beta Kappa. Among other compensating techniques, Rockefeller said he learned to concentrate intensely during class and, because reading was a labored process for him, got up at 5 every morning to study. Rockefeller went on to serve as governor of New York and vice president of the United States and was known to memorize speeches throughout his political career.

SEVERAL FEDERAL LAWS COMPEL Dartmouth and other institutions of higher education to accommodate students with disabilities. The main ones are Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and Title II of the ADA. The Rehabilitation Act applies to all colleges that receive federal financial assistance. (Stanzel and fellow students invoked Section 504 in their 1986 complaint against Dartmouth; the U.S. Department of Education investigated because its Office of Civil Rights is responsible for enforcement on college campuses.) The ADA extends the provisions of Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act to employers, government entities (including public colleges and universities) and other entities that serve the public (including private colleges). Both laws prohibit discrimination on the basis of disability, and have been interpreted by the courts to require colleges and universities to facilitate access to educational programs and facilities and to make reasonable academic adjustments. The ADA specifically says that students with disabilities are entitled to communication as effective as that provided to other students, with communication defined as the transfer of information." This information transfer must be timely, accurate and in a manner in which the student with a disability can understand it—large type, for example, for a student with limited vision.

The keyword in any curriculum modification for students with disabilities is that these changes are "reasonable." The federal laws largely leave this interpretation to individual institutions. Colleges are under no obligation to lower performance standards. They do have to delineate essential requirements from those that can be skipped and provide a means for eligible students to opt out of the latter. At Dartmouth, for example, students with documented auditory disorders such as May's are eligible to apply for a waiver from the foreign language requirement (which May chose not to do). But the engineering department has no obligation to overhaul its curriculum, say, for a student who is disabled in computation—a critically important skill in that subject.

Students, in turn, are required to meet all essential-academic and technical standards, and they can be barred from academic settings if their behavior—even if disability-related—threatens the health and safety of themselves or others. They also have to provide documentation of the disability for which they want accommodation. This typically includes reports from qualified professionals, and, when appropriate, test results that conform to certified diagnostic criteria, reevaluation if the diagnosis is more than three years old, evidence ruling out alternative diagnoses, and the rationale for specific accommodations.

As hard as they push for accommodation, Trueba and Thum emphasize that an equal part of their job is weeding out candidates who lack credible diagnoses.

SUCCESS IN DISABILITIES ACCOMMODATION in higher education is measured by graduation rates. At Dartmouth the track record of students with physical and learning disabilities is impressive: More than 90 percent graduate, comparable to the entire student population. For the minority of students disabled by psychiatric conditions including bipolar disorder, depression, schizophrenia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder and personality and anxiety disorders—success at Dartmouth is less predictable. Pompian, who tracked graduation rates from the late 1980s until her retirement, found they have lower graduation rates. She says the illnesses can have episodic exacerbations, and the medications used to control them may also have debilitating side effects. Unlike schools that permit part-time attendance, Dartmouth offers little leeway for students whose illnesses interfere with class attendance requirements and the workload of a typical 10-week term.

Pompian's observations mirror the state of things nationally. At the 28th annual conference of the Association of Higher Education and Disability, held last year in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, several sessions focused on the challenges presented by students with multiple and severe chronic conditions. Advances in medical science and pharmacology have made it possible for severely ill students not only to survive to college age but also to amass secondary school records entitling them to college admission.

The issues raised at the conference were not whether these students should be accommodated but how to meet their needs given limited budgets and staffs—and possibly competing interests in the larger student body. One session, for example, focused on Asperger Syndrome, a milder form of autism. Students with the diagnosis may perform brilliantly in the classroom and on tests, contributing significantly to intellectual discourse, but they may have great difficulty managing other aspects of college life—struggling, for example, with food choices in the cafeteria.

These and other sessions delineated the leading edge of challenges for disabilities accommodation in higher education. Some raised more questions than answers, highlighting the judgment calls that underpin accommodation.

"We can't guarantee success," reiterates Thum. "What we work hard on is that the student has an equal opportunity to demonstrate what he or she is capable of demonstrating."

The broader applicability to benefit a small minority of helps reduce the of what might have originated students stigma of disability.

Irene M. Wielawski, an award-winningfreelance journalist who lives in Pound Ridge, NewYork, authored DAMI's March/April-cover storyabout the teenage brain.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

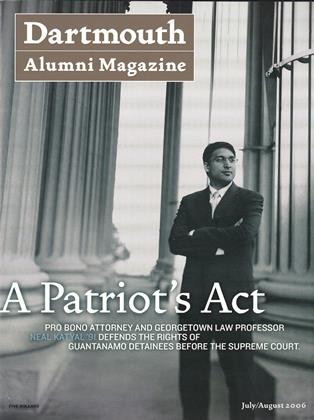

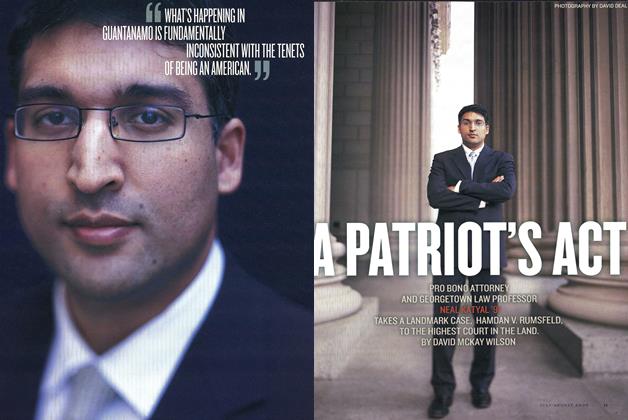

Cover StoryA Patriot’s Act

July | August 2006 By DAVID MCKAY WILSON -

Feature

FeatureMeet the Greeks

July | August 2006 By ALLISON CAFFREY ’06 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

July | August 2006 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

July | August 2006 By Rodger Ewy '53, Rodger Ewy '53 -

CAMPUS

CAMPUSMaking a Comeback

July | August 2006 By Lauren Zeranski ’02 -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONAcross the Divide

July | August 2006 By Lucas Swaine

Irene M. Wielawski

-

Feature

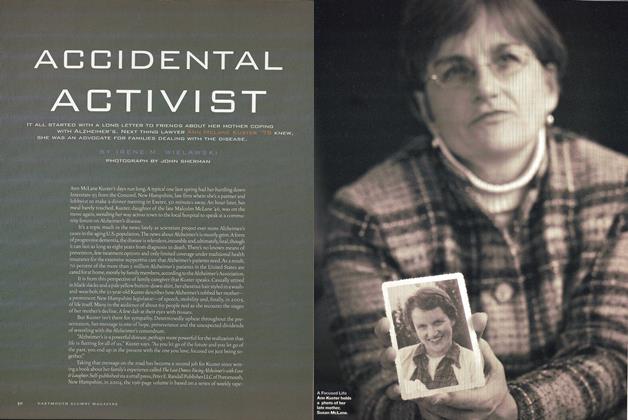

FeatureAccidental Activist

May/June 2008 By Irene M. Wielawski -

Cover Story

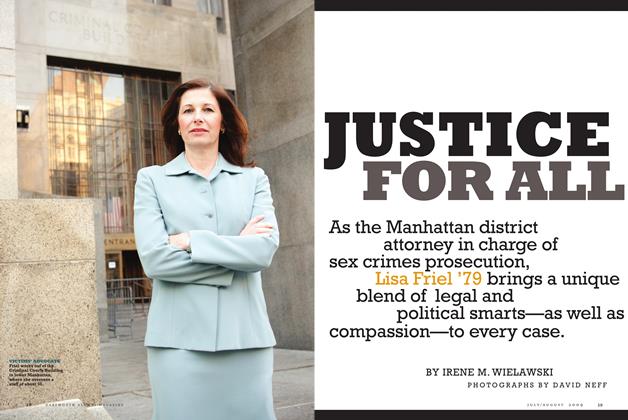

Cover StoryJustice for All

July/Aug 2009 By Irene M. Wielawski -

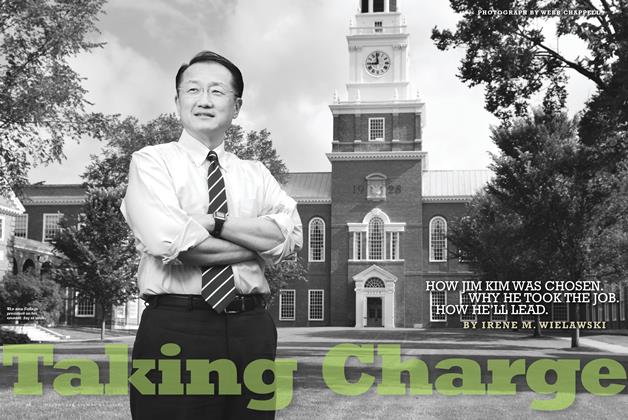

COVER STORY

COVER STORYTaking Charge

Sept/Oct 2009 By Irene M. Wielawski -

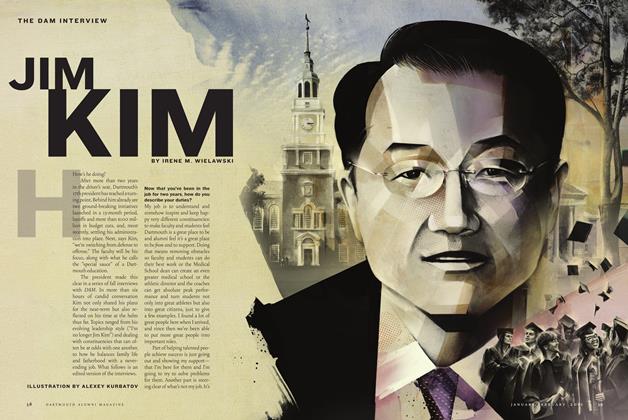

THE DAM INTERVIEW

THE DAM INTERVIEWJim Kim

Jan/Feb 2012 By Irene M. Wielawski -

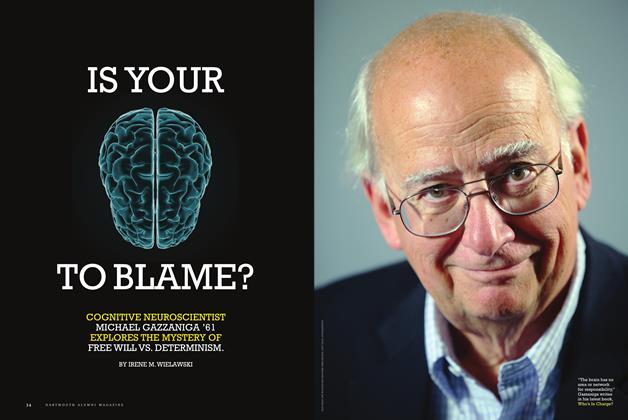

Cover Story

Cover StoryIs Your Brain to Blame?

Nov - Dec By Irene M. Wielawski -

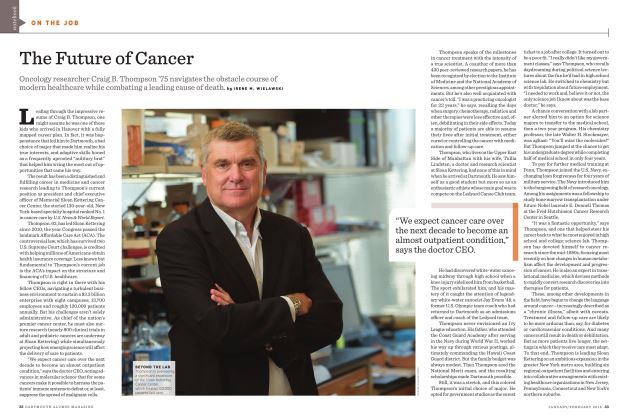

ON THE JOB

ON THE JOBThe Future of Cancer

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2016 By Irene M. Wielawski

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryMurray Hitzman '76

March 1993 -

Feature

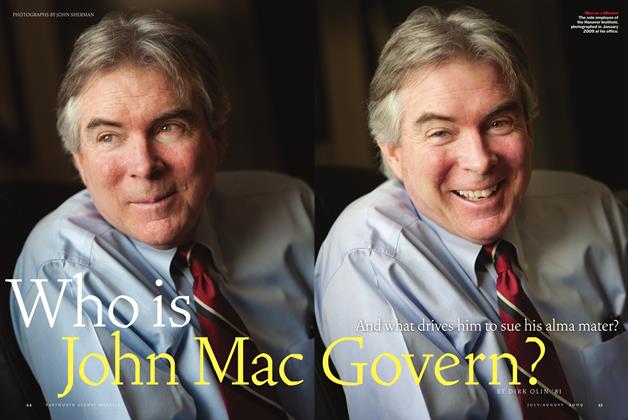

FeatureWho is John MacGovern?

July/Aug 2009 By Dirk Olin ’81 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Dartmouth Caucus

MARCH 2000 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

Feature

FeatureRisky Business

Mar/Apr 2001 By JAMIE HELLER ’89 -

COVER STORY

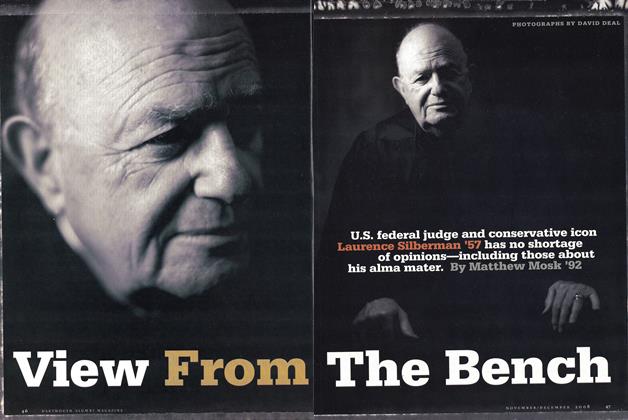

COVER STORYView From the Bench

Nov/Dec 2008 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Feature

FeatureDiary of a Long Distance Runner

SEPTEMBER 1987 By Tim Hartigan '87