Speaking in Tongues

One of America’s most respected language teachers questions the ability of the United States to communicate its messages abroad.

May/June 2006 John Rassias ’49A, ’76AOne of America’s most respected language teachers questions the ability of the United States to communicate its messages abroad.

May/June 2006 John Rassias ’49A, ’76AOne of Americas most respected language teachers questions the ability of the United States to communicate its messages abroad.

WHEN PRESIDENT GEORGE W. BUSH announced his National Security Language Initiative (NSLI) in January I was among those muttering "too little, too late." Lest this sound like sour grapes from a member of the Carter Commission on Foreign Language and International Studies that released broader recommendations more than 25 years ago, I invite readers to consider how different things might be if we had pushed for fluency in foreign languages out of basic humanitarian and cultural concerns rather than racing now to train people for the "critical" reason cited by the president: winning an ideological struggle.

While eagerness to learn about other countries is very evident at Dartmouthstudents continue to major in languages, study abroad and join the Peace Corps in impressive numbers—the same cannot be said nationally. U.S. Department of Education data shows fewer than 8 percent of U.S. college students take language courses and fewer than 2 percent study abroad.

The tragedy of the failure to value every language plays out daily on the world stage, where international understanding and cooperation depend on sensitive communication. Linguistic and cultural gaffes have marred many presidencies, contributing to a world view of Americans as country bumpkins with really big sticks and too-loud voices. When George W. Bush showed the sole of his shoe in front of a Saudi ambassador it was seen as a sign of scorn to a Muslim and indicative of Americas indifference to the ways of other races and nations. George H.W. Bush, in a cavalcade in Australia, as reported in the Washington Post on January 3, 1992, "Surprised protestors with an ambiguous hand gesture when he smiled from his limousine and waved the V-for- victory sign at them—with the back of his hand facing out. To Australians, that's a decidedly nasty gesture." Of course, it means "Up yours!" Richard Nixon's signature "A-okay" sign was not received kindly in Latin America because to Latinos he was saying, while smiling, "Screw you!" John F. Kennedy, in his famous 1963 "I am a Berliner" statement, grammatically identified himself not as a resident of Berlin but as a "jelly doughnut" when he added the article "Ich binein Berliner."

The CIA, which sought teachers of Arabic, Farsi, continental Portuguese, Russian, Turkish, Romanian and even French, Italian and Spanish during the 1979 Iran crisis, is still looking, tacking "Help Wanted" signs on telephone poles.

American investment in languages and area studies, long woefully inadequate, has slipped so far that the U.S. Foreign Service no longer has a language requirement, with the outcome that our diplomats are often the last to fathom upheaval or outrage right under their noses. U.S. Ambassador to Egypt Francis Ricciardone '73, who is fluent in several languages including Arabic, stands in stark contrast to many of his peers. On February 12 USAToday reported that only 10 of 34,000 U.S. State Department employees are considered fluent in Arabic.

The problem extends beyond the diplomatic into the business arena. Revenue lost pales beside respect lost as America peddles products the consumer cultures in other lands neither want nor need, from golf balls packaged in clusters of four for a Japanese outlet (the Japanese consider the number four unlucky) to green hats in China (where a green hat symbolizes infidelity).

Inappropriate, thoughtless advertising further diminishes trust and has led to numerous advertising blunders. Among them are Microsoft's slogan for Windows 95, "Where do you want to go today? "which was translated into Japanese as: "If you don't know where you want to go, we'll make sure you get taken." In China the Kentucky Fried Chicken slogan became "Eat your fingers off."

In March 2005 The Wall Street Journal cited General Motors Corp.'s misstep in running an ad for its Saturn automobile that featured a women in Mexican garb outside the Alamo—to win a largely non- Mexican audience in Miami. GM also failed to realize that its "breakthrough" slogan could not be communicated in Spanish, even with the employment of a Hispanic marketing firm. The firm promoted the Cadillac Escalade by showing it chasing bulls in Pamplona with a slogan of "avanza," which means not "breakthrough" but "advance."

As reported in Newsweek last spring, Coors beer also experienced the fallout of faulty translation when it attempted to communicate its "Turn it loose" campaign in Spanish. Before it realized its mistake and changed its message to "Won't slow you down" in Spanish, Coors was promoting its product with "Sueltalo," understood by Spanish speakers to be a reference to diarrhea: "Let it loose."

Well-ballyhooed national drives to learn languages, such as Bush's new initiative, reverberate and stir our blood to boiling temperature during critical times—but only as long as the crisis lasts.

According to the State Departments announcement, NSLI has three goals: "Expand the number of Americans mastering critical-need languages and start at a younger age; increase the number of advanced- level speakers of foreign languages with an emphasis on critical-need languages; increase the number of foreign language teachers and the resources." To accomplish these goals the administration offers a smorgasbord of financial incentives to teach and study critical languages, "continuous programs of study of critical languages" and immersion programs of study of languages, to summer and academic year study abroad for students and teachers. President Bush is asking for $114 million in the next fiscal year to get the effort under way. This may be another attempt at "shock and awe" but, as with military spending in Iraq, not all expenditures are projected into the future.

The plan is a step in the right direction, but it does not go far enough and promises more than it can likely deliver. I would urge reconsideration of the Carter Commission recommendations, which detailed when language should be taught and how—reinforced with programs throughout the year in regional centers, summer institutes and study abroad.

The Carter Commission recommended tapping two powerful resources within our society: immigrants and returned Peace Corps volunteers. Besides helping us learn their languages, immigrants can serve as resources for conversation and culture—a matter of pride in their heritage, a matter of efficiency for our illumination. Peace Corps volunteers, (whose numbers have swelled from 80,000 to more than 182,000 since our 1979 report), have absorbed languages and culture around the world and might be used to advance the study of less commonly taught languages.

The commission recommended that federal agencies with positions designated as requiring a foreign language competency should achieve 100 percent compliance with these requirements "as soon as possible and no later than 1985."

We citizens have to give our school boards a real mandate to teach languages seriously and integrally to the school curriculum, with real money to pay real teachers for real jobs. The stakes are high. Language articulates value, confirms or denies fact, soars or sinks with the human heart. Language makes things happen. And language can lead us to peace.

John Rassias is the William R. Kenan Jr.Professor and professor of French.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

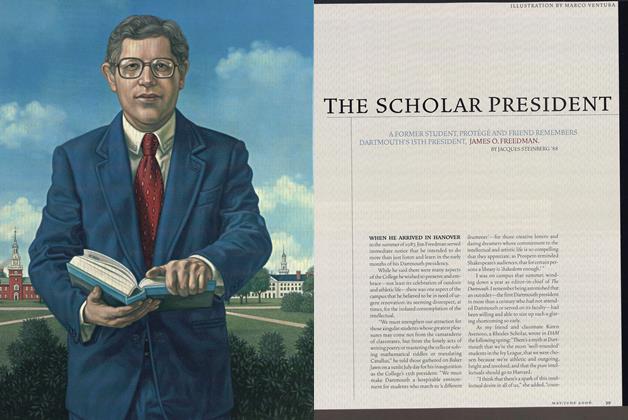

Cover StoryThe Scholar President

May | June 2006 By JACQUES STEINBERG ’88 -

Feature

FeatureCapitol Steps

May | June 2006 By ALICE GOMSTYN ’03 -

Feature

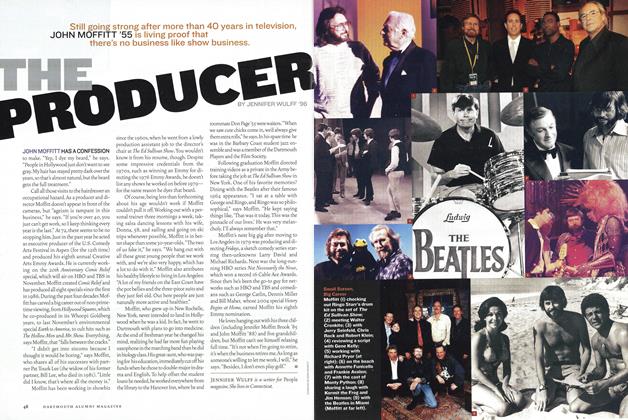

FeatureThe Producer

May | June 2006 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

May | June 2006 By JOE MEHLING '69 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

May | June 2006 By Gisela Insuaste '97 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

May | June 2006 By BONNIE BARBER

FACULTY OPINION

-

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONInvestor’s Ed

Nov/Dec 2006 By Annamaria Lusardi and Alberto Alesina -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONLive Free or Die?

Jan/Feb 2009 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionSaturate, Don’t Isolate

Mar/Apr 2004 By David C. Kang -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONA Well-Traveled Story

July/Aug 2009 By Ernest Hebert -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONAcross the Divide

July/August 2006 By Lucas Swaine -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONThe Ultimate 24 Hours

MAY | JUNE 2014 By RIANNA P. STARHEIM ’14