Walls That Talk

The study of American architecture can teach us as much about history as it does about design.

May/June 2009 Judith HertogThe study of American architecture can teach us as much about history as it does about design.

May/June 2009 Judith HertogThe study of American architecture can teach us as much about history as it does about design.

IT IS NO COINCIDENCE THAT WHEN PRESIDENT DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER visited Dartmouth in 1953 and glanced at the campus buildings around him, he remarked, “This is what a college should look like.” According to Marlene Heck, who teaches “Building America: An Architectural and Social History,” Eleazar Wheelock took great care to make Dartmouth look exactly the way a college was supposed to look. She says that in order to win over prospective students, the College founder modeled Dartmouth on more established institutions and built Dartmouth Hall as an almost exact replica of Princeton’s Nassau Hall. “Wheelock used architecture to create legitimacy for his school; he could only attract students out into this wilderness by carefully projecting an image of civilization,” says Heck.

Heck teaches her students that architecture is concerned with much more than shelter, comfort or aesthetics: It is the material manifestation of the values and ambitions of a society and it forms the world we inhabit. “We live in it,” says Heck, “we study within its walls, we’re healed within its walls when we get sick, we seek solace in churches and synagogues and mosques—architecture is omnipresent and we need to know about it and understand how it works.”

Heck sees American architectural history as illuminating the changing values and concerns of American society— from the colonial impulse to civilize the wilderness to the post-revolutionary desire to establish an independent identity based upon the ideals of the Enlightenment, from the emergence of large cities during the Industrial Revolution to the formation of suburbs as a refuge from those cities, from the American dream to the current housing crisis.

To illustrate how architecture was used to convey social status as 18th-century American society became more class conscious, Heck shows her students slides of the most famous colonial buildings of Newport, Rhode Island, which, as a trading center for rum and slaves, was more prosperous, sophisticated and cosmopolitan than any other New England city at the time. As the students view images of the Touro Synagogue, the oldest surviving synagogue in the United States, and of Redwood Library, the oldest library in the country, Heck asks them to consider what these buildings, both designed in the mid-18th century by Peter Harrison, can teach us about the people who constructed them.

As the class looks at the solemn, temple-like façade of the library, which was the first classical-style building in America, Heck explains that in a society where most people could barely afford to own a family Bible, a library was a precious sanctuary of knowledge and civilization, accessible only to the most distinguished and wealthy. Heck points out that the Touro Synagogue’s relatively simple exterior may indicate the Jewish community’s desire to blend in and not draw too much attention to itself. The synagogue’s interior, which was inspired by the Sephardic synagogue of Amsterdam and the Palace of Whitehall in London, reveals the community’s international roots.

Heck says her teaching has changed over the years. She initially felt a need to cover every important building in American history, but now has come to believe just as much can be learned from less famous architecture. “Buildings are cultural documents,” she says. “They are sending us messages about the culture that created them.” Heck understands students won’t remember all the particulars about the buildings they study and will forget the dates and the architects. “But,” she says, “I hope they’ll retain a general understanding of how architecture works.”

“Isn’t this magnificent!” Heck exclaims as she takes her students on a visual tour of Mount Vernon, George Washington’s plantation home in Virginia. She explains that because the agricultural South had fewer cities and public buildings than the North, public life took place at private houses, which explains the size and sumptuousness of the plantation homes. She shows images of the Mount Vernon driveway as it winds through lawns, forests and fancy gardens and describes this as a “processional landscape,” designed to impress upon visitors the size of the estate and the prosperity and refinement of the owner. She shows the imposing façade and lavish entrance hall, where a visitor would wait to be received.

The historical study of architecture is also concerned with the flip side of all this grandeur. While planters built and landscaped for themselves, they were oblivious to the parallel landscape that formed the world of their slaves, Heck says. She follows the slides of the splendors of Mount Vernon with images of the slave quarters on the grounds and explains that slaves did not use the central staircases in their masters’ houses. Instead they used simple, hidden, undecorated stairways. Likewise slaves did not travel on main roads. They used a network of back roads to travel between plantations.

Heck says anything that goes on in society can be read in architecture, and evolution in architecture can be linked to a social change. “Every time you see people starting to build differently, you have to ask what’s going on in this culture,” says Heck.

Yet architectural traditions also persist and themes are passed on through the generations. When Wyatt Levinson McKean ’11, a student whose father owns a construction business, learned that Southern planters used to decorate the exterior of their homes with wood that was treated to look like stone, he immediately saw a parallel in contemporary architecture. “This right away conjured images for me of these bloated stucco buildings with a thin veneer of cultured brick,” he says. McKean decided to write his final paper for the course on the recent trend toward oversized “McMansions” and the illusory quality of American residential architecture.

This is the kind of insight Heck finds gratifying. “I just love teaching American architecture,” she says. “It’s so much fun to open students’ eyes and make them notice things they hadn’t been paying attention to before.” Heck has taught the course regularly since 1992. The absence of an architecture department at Dartmouth has not prevented her from encouraging an interest in architecture among students. Together with Karolina Kawiaka, who teaches architecture in the studio art department, Heck organizes architectural campus tours, invites influential architects for lectures and advises the student architecture club, ARC@D. Every year a number of her students continue on to renowned architecture schools hoping for careers like that of Michael Arad ’91, who designed the World Trade Center Memorial, and William McDonough ’73, the well-known “green” architect.

While Heck hopes to encourage more graduates to become practicing architects, she sees value in her course for any student. “Having visual literacy and a sense of what buildings tell us is not only helpful in our day-to-day life,” she says, “but if you go anywhere in the world you’ll have an entry into that culture and you can understand it through its architecture.”

Heck speaks from experience. Her first childhood memories are of driving with her family from Texas to Pennsylvania to visit her grandparents. She says she would observe the architectural landscape from the backseat window. “I didn’t have the language to talk about it,” she explains, “but I was aware that these places just looked different from what I knew, and I remember thinking we must be getting close to grandma’s house because the buildings started to look a lot like grandma’s.” Heck says she still feels more at home in the Texas landscape than in the mountains of New England. “It shows the power of architecture and of place,” she says. “It’s deeply etched into our consciousness, in ways we can’t even begin to imagine.”

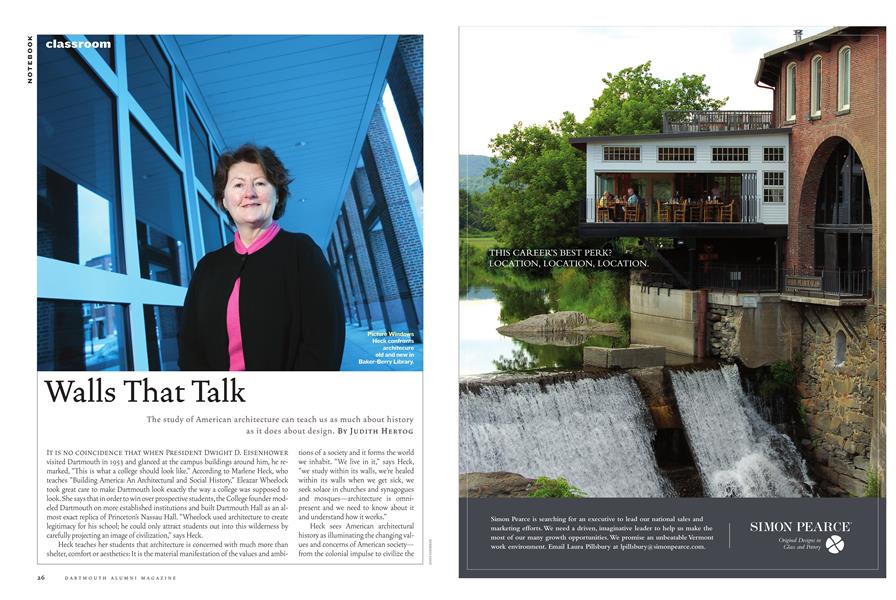

Picture Windows Heck confronts architecure old and new in Baker-Berry Library.

“Buildings are cultural documents. They are sending us messages about the culture that created them.”

Building Blocks For anyone interested in learning about social change as reflected in American architecture, Professor Heck suggests the following: The Refinement of America: Persons, Houses, Cities by Richard Lyman Bushman (Vintage, 1993) Of Consuming Interests: The Style of Life in the Eighteenth Century by Cary Carson and Ronald Hoffman, edited by Peter J. Albert (University of Virginia, 1994) Building the Nation: Americans Write About Their Architecture, Their Cities and Their Landscape, edited by Steven Conn and Max Page (University of Pennsylvania, 2003) Makers of Modern Architecture: From Frank Lloyd Wright to Frank Gehry by Martin Filler (New York Review Books, 2007) Architecture in the United States by Dell Upton (Oxford University Press, 1998)

JUDITH HERTOG lives in a 1980s ranch- style house in Norwich, Vermont.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA World of Difference

May | June 2009 By CATHERINE FAUROT, MALS’04 -

Feature

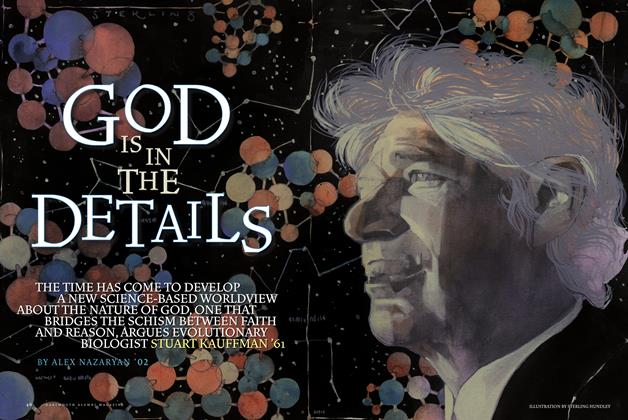

FeatureGod Is in the Details

May | June 2009 By ALEX NAZARYAN ’02 -

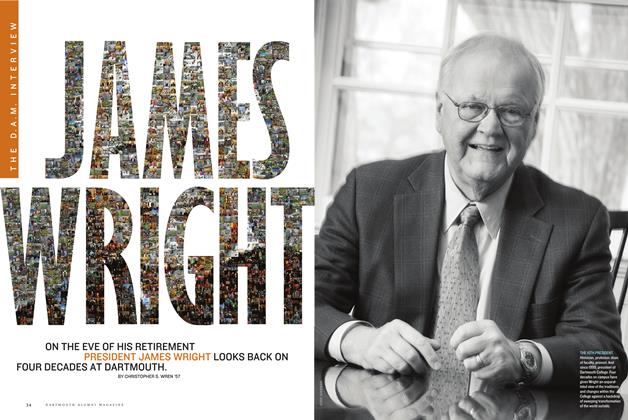

THE DAM INTERVIEW

THE DAM INTERVIEWJames Wright

May | June 2009 By CHRISTOPHER S. WREN ’57 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

May | June 2009 By BONNIE BARBER -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONSlow Medicine

May | June 2009 By Dennis McCullough, M.D. -

SPORTS

SPORTSIn a League of His Own

May | June 2009 By Brad Parks ’96

Judith Hertog

-

Article

ArticleDefining Wilderness

Jan/Feb 2007 By Judith Hertog -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMPoetry in Motion

May/June 2007 By Judith Hertog -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMLearning Curve

Jan/Feb 2008 By Judith Hertog -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMAll About Algorithms

Sept/Oct 2010 By Judith Hertog -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMPhilosophy Camp

Mar/Apr 2013 By Judith Hertog -

TECHNOLOGY

TECHNOLOGYA Monitored State

JULY | AUGUST 2016 By JUDITH HERTOG

Classroom

-

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMA Body in Motion

MAY | JUNE 2018 By GEORGE M. SPENCER -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMNot Lost in Translation

Sept/Oct 2009 By Judith Hertog -

Classroom

ClassroomWestern Civilization

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2017 By JUDITH HERTOG -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMCode of Life, Codes of Conduct

Sept/Oct 2000 By Karen Endicott -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMFrom the Page to the Stage

Mar/Apr 2002 By Karen Endicott -

Classroom

ClassroomThe Art and Science of Group Dynamics

Nov/Dec 2002 By Karen Endicott