President Ernest M. Hopkins of Dartmouth has seized the opportunity presented by the opening of the college season to utter an unusually stimulating thought. The time has come, he told the new students he was welcoming, "for us to say in our colleges what many of us acknowledge to ourselves, that there is fully as much need for a constituency educated to choose its leaders as there is for educated leaders themselves."

Many of our colleges were founded for the purpose of training leaders and the idea has persisted that this is the main function of higher education. The original purpose in the older colleges was to fit men to exercise their leadership in the ministry. Later the idea broadened to take in all the professions, then to include the business world and, finally, to furnish political leadership. President Hopkins confessed that he once shared that idea himself, but now recants. His revised view is that the business of higher education is not to train men for leadership, but to educate them for usefulness. He believes they are as much needed in the rank and file of the electorate as they are in public offices.

There has been a good deal of talk recently about the lack of great leaders. This does not worry President Hopkins as much as the lack of an intelligent electorate, interested in public affairs, that can be depended upon to elect capable representatives. He has a sound view of democratic government. The people are sovereign. He sees the hope of democracy in an intelligent sovereignty. From this viewpoint, it follows that the business of education is to elevate the intelligence and civic interest of the constituencies. President Hopkins makes this deliberate statement: If the only options available to this college were to graduate men of the highest brilliancy intellectually, without interest in the welfare of mankind at large, or to graduate men of less mental competence, possessed of aspiration which we call spiritual and motives which we call good, I would choose for Dartmouth College the later alternative.

Simply to state this attitude should be a rallying cry to the educated men and women of the country to rouse themselves to their civic duties. It is notorious that those who consider themselves in the "better class" shirk their duty at the polls and then complain that democracy is a failure. There would be less danger of democracy's failing if they would use their intelligent votes to make it a success.—Newark Evening News.

In an editorial headed "Wise Words by College Presidents" the Chicago Evening Post comments: "Another interesting utterance comes from President Hopkins of Dartmouth. Said he:

" 'lf the only options available to this college were to graduate men of the highest brilliancy intellectually, without interest in the welfare of mankind at large, or to graduate men of less mental competence, possessed of aspirations which we call spiritual and motives which we call good, I would choose for Dartmouth college the latter alternative. And in doing this I should be confident that this college would create the greater values and render the more essential service to the civilization whose handmaid it is.'

"That, also, is a note which cannot be struck too often or too clearly. If education fails to give a man a sense of the supreme importance of spiritual values, and an outlook on his world as a field for service, then it fails to justify itself so far as he is concerned. We have today too many brilliant futilitarians, who dazzle with their intellectual cleverness, but make no contribution to the needs of their time and their fellows. The president of Dartmouth puts the stress where it should go, and we believe that there are many others at the heads of our institutions of learning who agree with him in the objective he chooses."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTODAY'S RESPONSIBILITY OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE

November 1927 By President Ernest M. Hopkins -

Article

ArticleDICK'S HOUSE

November 1927 By Eugene Francis Clark '01 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

November 1927 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1899

November 1927 By Louis P. Benezet -

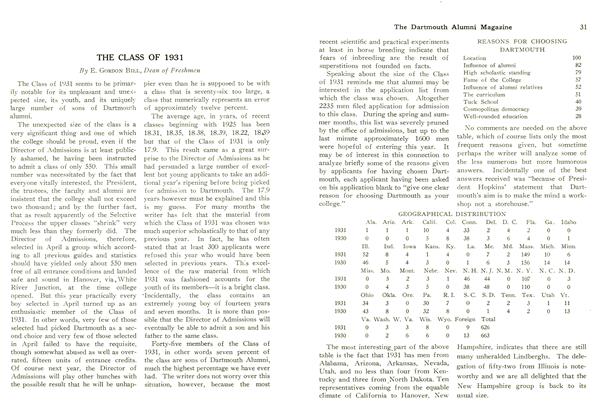

Article

ArticleTHE CLASS OF 1931

November 1927 By E. Gordon Bill -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1911

November 1927 By Prof. Nathaniel G. Burleigh