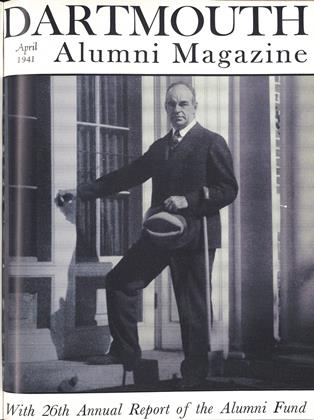

TO ONE WHO HAS SPENT A LIFETIME lurking behind an editorial "we" it is welcome now and then to slip out of his customary anonymity and assume the more intimate guise betokened by the byline. It is peculiarly welcome when such an assignment involves the penning of a panegyric on a life still in vigorous being, in recognition of a record' for conspicuous achievement, such as that which President Hopkins has made during the twenty-five years of his presidency at Dartmouth. This is no chiseling of an epitaph to grace a storied urn or animated bust; rather is it a pause in the day's occupation to set down an appreciative word in mid-career. It adds to the pleasure of doing it to know that "Hop" as we know him without disparagement of academic dignity—is today in body and mind at the top of his form, with what should be many more years of activity before him, as well as an honorable past behind.

The years fly swiftly. It doesn't seem a quarter century since the late E. K. Hall, then an alumni trustee of Dartmouth, told me that the board had chosen Ernest Martin Hopkins to succeed President Nichols at the head of the College organization. It is hard to believe that twenty-five years have elapsed since I came to Hanover to attend the ceremonies incident to his induction. I must accept the testimony of the calendar, however incredible that testimony may seem, and contemplate with unfeigned enthusiasm the scroll on which the record of those eventful years is transscribed. It is indeed a noble record, one of which every Dartmouth man must be proud. To "Hoppy" has been vouchsafed the high privilege of carrying the College to a position of honor and efficiency never before attained by it in the long and inspiring history of its more than 170 years, a scope undreamed of either by Eleazar Wheelock, who founded it, or by William Jewett Tucker, who inaugurated the greater Dartmouth of the later years.

Beyond question the new president derived his chief inspiration de-from his personal service, as a young graduate, in the Tucker administration, of which it was his privilege to be an essential part. I doubt that Dr. Tucker realized that in those early years of the New Dartmouth he was grooming his eventual successor; but such was the fact, and to Dr. Hopkins was transmitted that vital spark which Dr. Tucker enkindled and which was already a burning and a shining light. The disciple owes much to the teacher—and I imagine would be the first to acknowledge it.

THE GREAT DIFFICULTY IN my present task is to find anything to say that we do not already know—all of us in the Dartmouth fellowship. What President Hopkins is, and has done, is common knowledge among us. But it has been my privilege, in protracted service in the Alumni Council and as an alumni trustee, to come into more intimate contact than most with the man and his work, to see and to know at first hand the manifold complexities and problems of the office, and to appreciate beyond what is possible to most the consummate skill with which those problems and complexities have been handled. I doubt that any job, unless it be that of the impresario of the Metropolitan Opera, involves more intricate situations than those besetting the president of an American college, or brings into play a greater number of conflicting strains and stresses. Consider that every college presents a tripartite—perhaps better a fourfold—entity, with diverse interests to be harmonized and served; to wit, those of its trustees, faculty, alumni and undergraduates. To deal with these so as to produce the maximum of efficiency and a minimum of soreness demands a talent for diplomacy of no mean order; and on top of these a talent for finance, for revenue raising and for budget balancing, which, especially in present conditions, must produce their full quota of headaches.

In the last analysis every really big job is a one-man job, and it is peculiarly true of the job of a college president, who must be as tactful as he is tireless. I do not regard it as a rash exaggeration to say that no educational leader in contemporary America has succeeded better than President Hopkins in keeping things running true. One must be bold—but not too bold; firm—but not too firm; liberal—but at the same time reasonably conservative. Happy the college oppos-ipresident who can produce, as the evidence of his success, such an enthusiastic anid happy family as the present Dartmouth fellowship—undergraduates, faculty and alumni—with undimimished unity after twenty-five years of service. New brooms sweep clean, but it is a wholly unusual broom that not only does not diminish, but actually increases in virtue with the lapse of time and with constant use.

I believe it was the estimable woman who subsequently became the wife of crusty old Samuel Johnson who remarked, after first meeting him, that he was the most sensible man she had ever encountered. If I had to select a single outstanding quality as characteristic of President Hopkins, I should without hesitation name that most uncommon of all human qualifications—common sense. If there is a prominent American educator now living who is more generally or more approvingly quoted than Dr. Hopkins, I don't know who he is. The reason, of course, is that what Hop says is not only what he honestly thinks, but is pretty sure to be right in the intelligent estimate of men. It takes a good deal of courage sometimes to take a right position, but in his case there has never been any lack of courage. There is need of pungency to make a position clear and to put it across—but there has been no lack of that quality when the occasion demanded it. Originality of thought might be overdone and thereby cease to be a virtue, but my feeling is that our "Hop" avoids that easily besetting sin. To be progressive without being headlong, to be far-sighted without being visionary, those are conspicuous virtues which the experience of twenty-five years has proved that President Hopkins possesses in full measure.

For the attainments of those twenty-five years there is, of course, a reason and the reason is the character of Ernest Martin Hopkins. The foundations were well and truly laid; and on those foundations a master hand has reared a superstructure of which we may be—and are—justly proud.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureReport of Twenty-Sixth Alumni Fund

April 1941 By SUMNER B. EMERSON '17 -

Feature

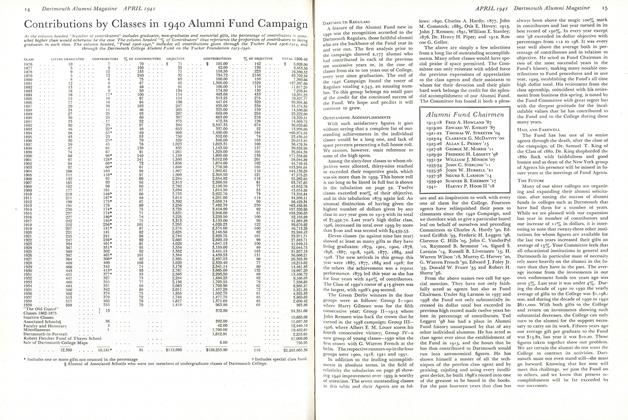

FeatureContributions by Classes in 1940 Alumni Fund Campaign

April 1941 -

Feature

FeatureThayer School Report

April 1941 By F. H. Munkelt '08 (Thayer '09) -

Feature

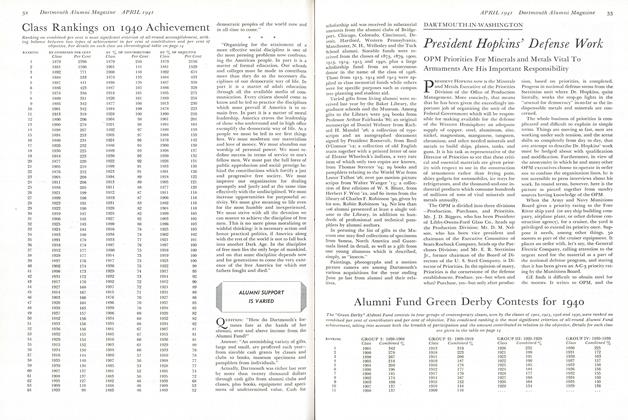

FeatureClass Rankings on 1940 Achievement

April 1941 -

Feature

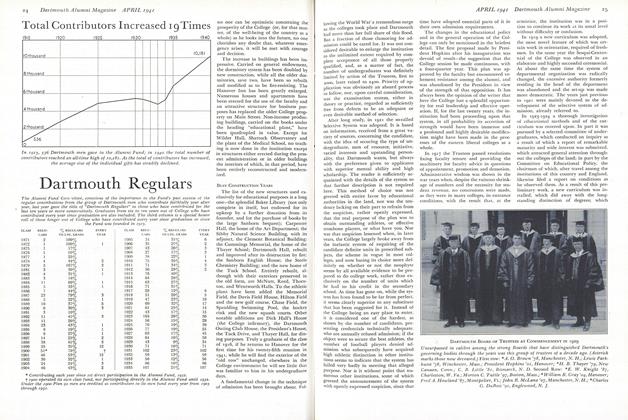

FeatureDartmouth Regulars

April 1941 -

Feature

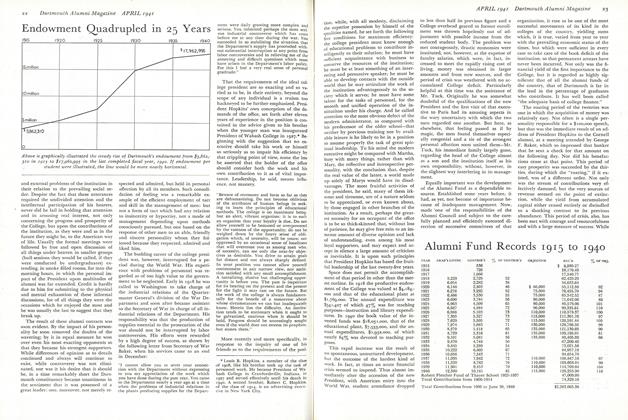

FeatureAlumni Fund Records 1915 to 1940

April 1941

Philip S. Marden

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1894

October 1951 By CHARLES C. MERRILL, WILLIAM M. AMES, PHILIP S. MARDEN -

Article

ArticleArthur Sherburne Hardy

DECEMBER 1930 By Philip S. Marden -

Class Notes

Class Notes1894

November 1955 By REV. CHARLES C. MERRILL, WILLIAM M. AMES, PHILIP S. MARDEN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1894

January 1956 By REV. CHARLES C. MERRILL, WILLIAM M. AMES, PHILIP S. MARDEN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1894

January 1958 By REV. CHARLES C. MERRILL, WILLIAM M. AMES, PHILIP S. MARDEN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1894

By REV. CHARLES C. MERRILL, WILLIAM M. AMES, PHILIP S. MARDEN, 1 more ...

Article

-

Article

ArticleFROM THE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

February, 1924 -

Article

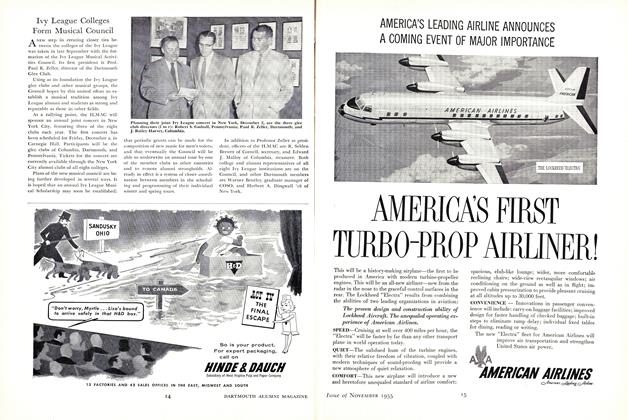

ArticleIvy League Colleges Form Musical Council

November 1955 -

Article

ArticleListening Post in Orbit

NOVEMBER 1965 -

Article

ArticleClub President of the Year

NOVEMBER 1969 -

Article

ArticleGarbage Collectors

November 1976 -

Article

ArticleFurther Mention

JUNE 1972 By JOHN HURD '21