by HenryBailey Stevens '12. Harper & Brothers, 1949;247 pages; #3.

Mr. Stevens has written unquestionably a most important and thought-provoking book proving that Hobbes' theory that primitive man's life was a blind struggle of treacherous carnivores is false, and offering us a chance to recover a true culture.

This knowledge proving Hobbes wrong has come to us piecemeal, but Mr. Stevens for the first time in so intelligible a form has coordinated this knowledge and summed it up. His results will be startling to most, and if not convincing to all (and his thesis does have weaknesses of course), will at least make a deep, and I hope lasting, impression. As Gerald Heard puts it, "the story seems to be that man for millennia was mainly frugiverous and peaceful," and how man went wrong and how a true culture may be achieved is the immense task Mr. Stevens sets himself to expound and he does it deftly and lightly and with considerable charm. He has facts, a wide erudition in many fields, and the ability to find meaning in history, anthropology, etc.

The primary question, he finds, is something like this (p. 184): "Shall we continue to freeze our agricultural land to a livestock economy, huddle into abnormal treeless cities, create new deserts and hide behind armed borders? Or shall we develop our country into a garden?" and he concludes, "The only lasting national defense is a proper use of theland."

It is his contention that "the garden of this world is overrun by one and a half billion meat animals—cattle, sheep and swine—which eat up the grains and the grasses, and injure and trample out J:he trees, requiring five times as much land as man would need if he kept to his primate (vegetarian) diet." It is true that our earth is steadily losing its fertility and agriculture operates at a constant loss (we have lost a third of our topsoil since 1776) so far as the total economy is concerned. The abuse of the land results in greater pressure for it. Restrictions multiply as do nationalistic and racial feuds. "Mankind is facing an abyss today because at some point in the past it took a wrong turn."

Mr. Stevens is an evolutionist and in his statement that "we are what we eat" (p. 15) shares, I presume, the materialism of Feurbach, who was one of the mentors of that bogey man Karl Marx. Our blood structure is so similar to that of the chimpanzee and the gorilla that we can catch influenza from them. It was when, Mr. Stevens writes, "man found that he could effect his food supply through the selection and plantings of seeds and cuttings and the improvement of soil conditions, that he started the great upward spiral that set him above the apes." This is where culture evolved from the simple primate into the complex human. We were children of the trees as were our ancestors which explains the symbolism of the tree in primitive religions.

The Cain-Abel story correctly epitomizes a basic conflict between Nomadic herdsmen and settled croppers. (One was a gardener and the other a herdsman.) When we became meat-eaters we became warriors and the "culture of blood" sprang up which has possessed us ever since, culminating in the mass slaughter of Hiroshima. It was the Shepherd Kings who began aggressive warfare somewhere between 2000 and 1500 B.C. Hithertofore, the author contends, the food-gathering stage of history was free of war. With the breeding of animals an intolerable burden was thrown upon the soil resources of the earth and man has been paying for it with war ever since. So with meat eating man fell "below the level of the ape, of the monkey, of the entire primate family. He fell beyond the level of the last sixty million years into the class of the carnivores.... the beasts of prey." When man became proficient in animal husbandry he became proficient in war. And then came the payoff in strife with which our generation is most familiar.

Mr. Stevens has read widely in Frazer's The Golden Bough, a monumental work in the study of magic and religion, in the philosophies of China, India, Java, Europe, and Africa. He finds his own philosophy partly from Lao-Tze which is, I gather, that men should follow nature and not interfere with the natural goodness of man. He agrees with Richard Wagner that "the degeneration of the human race has been brought about by its departure from its natural food." He is one with Tolstoy, Shelley, Gandhi, and G. B. Shaw. He is one with the vegetarians; with the believers in non-violence. He is, in a phrase, one with Christ, "The Lord of the Faithful Tree."

The transgression of the primate law, breeding and slaughtering animals for human consumption, has been proved directly responsible, so Mr. Stevens says, for high blood pressure and for many foul diseases of our time and is a suspected cause of our physical degeneration as compared to other anthropoids. No cases of cancer, insanity, or poliomyelitis occur among the great apes. (They are vegetarians.) We are the carnivores with an atom bomb to dispose of. Alas alack; now we can understand the significance of Johnny Appleseed. Let Mr. Heard have the last word: "But for everyone interested in history Mr. Stevens' thesis is one of the most stimulating that the revolution in history has so far given us."

Mr. Stevens is one who was literally created to lecture in the Great Issues course as he discusses with tolerance and intelligence the greatest and most fundamental issue of all .... the recovery of culture. A most impressive book which I urge you to read.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesD. N. A. A.

February 1949 By MAX PRYOR, J. FREDERICK PFAU III -

Article

ArticleThe Indian Sharpens Up His Gridiron Tomahawk

February 1949 By BILL CUNNINGHAM '19 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1937

February 1949 By ROBERT P. FULLER, ARTHUR H. RUGGLES JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

February 1949 By HENRY R. BANKART JR., FREDERICK T. HALEY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1928

February 1949 By OSMUN SKINNER, RUPERT C. THOMPSON JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

February 1949 By A. W. LAUGHTON, WILLIAM H. SCHULDENFREI

Herbert F. West '22.

-

Article

ArticleLetters

December 1946 -

Article

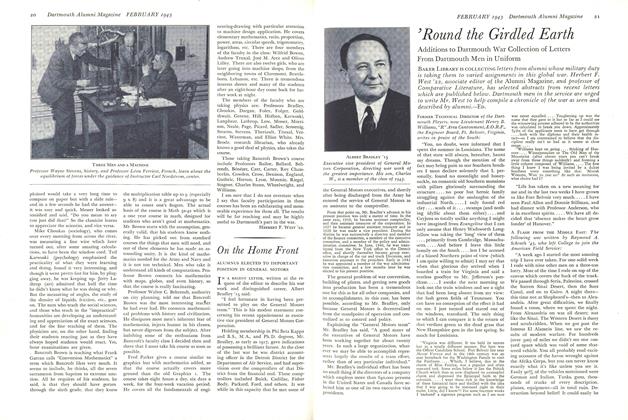

Article'Round the Girdled Earth

February 1943 By Herbert F. West '22. -

Books

BooksTHE WAYWARD PRESSMAN,

December 1947 By HERBERT F. WEST '22. -

Books

BooksLINE OF DEPARTURE,

February 1948 By Herbert F. West '22. -

Books

BooksCOPS OR CORPSES,

November 1948 By Herbert F. West '22. -

Books

BooksTHE COLONEL'S LADY,

March 1949 By Herbert F. West '22.

Books

-

Books

BooksTHE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF JOHANNES BUTZBACH, A WANDERING SCHOLAR OF THE FIFTEENTH CENTURY.

June 1936 By Ashley K. Hardy '94 -

Books

BooksFAMILY ARK.

JANUARY 1967 By CHARLES E. BREED '51 -

Books

BooksGAUSERIES—LA VIE SCOLAIRE,

November 1949 By Charles R. Bagley -

Books

BooksEXPECTANT PEOPLES.

OCTOBER 1964 By FRANK R. SAFFORD -

Books

BooksBOSWELL'S POLITICAL CAREER.

JULY 1965 By JEFFREY HART '51 -

Books

BooksFUNDAMENTALS OF SOCIAL SCIENCE

October 1946 By Robert K. Carr '29