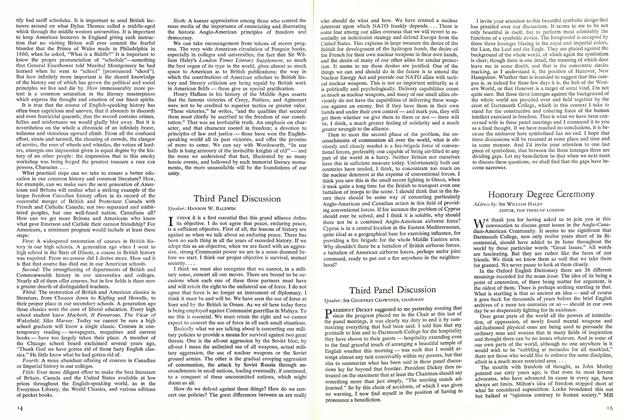

CHAIRMAN, HYDRO-ELECTRIC POWER COMMISSION OF ONTARIO

FACED as the Western World was, and still is, by the aggressive and expansionist designs of Soviet imperialism, it became abundantly clear that no state, however powerful, could guarantee its security by national action alone. The formation of NATO in 1949 was the answer. That NATO fulfilled its original purpose by removing the temptations to aggression, which arise from disunity and weakness, is generally acknowledged. But it was equally recognized, especially after the Geneva Conference, and the easing of world tension through the honeyed words of Russian insincerity, that fear of aggression alone is an insufficient foundation for the permanent establishment of the Atlantic Community. Deeper roots in political and economic cooperation must be sought if this protective shield against aggression is to be forged in the armory of freedom. This is just as essential today as when NATO was founded eight years ago.

The second great issue which carries hope for this troubled world is the trend towards European unity. When judged against the background of divergent interests and ancient enmities, the growing acceptance of this concept of an international community in Europe has made surprising progress. It is born of the realization by many European states, who have watched the fate of the captive countries, that notwithstanding their widely different backgrounds they can better defend their independence, and meet the economic and political problems of today, united than alone If joined economically, and in the more distant future united in some form of federation, they would indeed be a strong defense against Eastern aggression and an enhanced source of prosperity and economic stability for the Western World.

Here then are the twin objectives: a strengthened and broadened NATO and an integrated Europe, towards which the Western World should aspire and labor. Herein lies our greatest hope for world peace. But there is little likelihood of either of these objectives being attained unless they are resolutely sponsored and supported by the strength and prestige of North America and Britain acting as independent associates in their approach to the political and economic problems involved. . . .

Unity, if it is to be effective, cannot be confined to the political arena alone. International cooperation in the political field and international conflict in the economic field can rarely be reconciled.

The problems of unity in Canada and the U.S.A. and Canada and the United Kingdom are comparatively simple. Through evolution rather than revolution we in Canada

have developed slowly, but as swiftly as we ourselves wished, towards full and independent nationhood without losing our affiliations with the ancient lands to which we are still tied by bonds of racial origin, of affection, of common love for free institutions, and of self-interest. As regards the United States, we are bound to them by ties of neighborliness, of understanding, of economic interdependence, and of warm admiration for the generous role which they have played in the maintenance of peace and the establishment of security for smaller and weaker nations.

We are by far your biggest customer, and it is no doubt comforting and reassuring to you to have a friendly and dependable neighbor on your northern flank. But we fully recognize that whereas we are interdependent, we are more dependent on you than you on us. We do not, however, always find ourselves in agreement with some of your policies, either political or economic, and it would be erroneous for either the United Kingdom or you to assume that because of the closeness of our ties and the warmth of our affection, our support should at all times be taken for granted. There are indeed rumblings of discontent against the U.S.A.'s commercial and economic policies in Canada, which might well become serious unless suitable remedies are soon found.

This situation has been brought about, not only by the fact that our imports from you have exceeded our exports to you by nearly $1,300,000,000 last year, but because the magnitude of U.S. investments in our country has awakened fears in the minds of many that we may lose control over our economic destiny. Other factors, some of long standing, aggravate the situation. I will point out a few of these.

Our labor unions are largely affiliations of yours and their leaders take their orders from headquarters in the United States, and in consequence our economy is affected by decisions taken beyond our borders.

U.S. ownership of many of our basic industries fail to recognize Canada's natural desire for participation.

Notwithstanding our adverse trade balance, U.S. customs duties, regulations and administrative practices impede the growth of our secondary industries and make it difficult for us to correct the damaging unbalance in our trade.

Opportunities for export, the very lifeblood of our country, are frequently arbitrarily diverted from Canadian subsidiaries to the parent company in the United States; and are therefore lost to the Canadian economy.

Our Western Provinces are being seriously affected by your policy of selling wheat surpluses on a noncommercial basis to our natural and traditional customers.

Corporate giving by U.S. subsidiary companies is often less generous because, as they frequently tell us, "we are doing our major giving at home" and in consequence Canadian companies are obliged to shoulder a larger share of the load.

All these factors, which tend to cause disunity between us, have been partially recognized by you in the recent formation of the Stuart-Fowler Committee of the National Planning Association.

It is urgent that remedial action be taken lest this growing irritation degenerates into more serious misunderstanding. Ugly words such as "economic colonialization" are already being bandied about by irresponsible persons. . . .

The unity between the U.S.A. and Britain, if more important, is more complex, as the relations between greater powers are wont to be. It would be well if men of good will and influence on both sides of the Atlantic could take time off, as we are doing at this Convocation, to reappraise the situation which has resulted from the passing of world leadership from Britain to the U.S.A. and make allowance in so doing for the British bewilderment and occasional disappointment which have resulted from it.

Britain, on her side, should realize that world leadership, with all its momentous problems and responsibilities, was never sought by the American people, whose instinct as a great continental power separated by the Atlantic Ocean from most of the world's troubles was to remain aloof from foreign problems and entanglements. The inevitability of destiny has sent Main Street rambling all over the earth.

Yet, unprepared, and at times unwilling, the United States has assumed the mantle of leadership with generosity and effectiveness. Imperfect, inexperienced and mistaken as her stewardship has at times appeared to others, we would all be living in a very different world if the strength and determination and courage of the U.S.A. had not barred the way to Communist aggression. This is a fundamental and historic truth which Britain and the Western World should never forget.

The United States, on the other hand, should remember that Britain has carried the burden of world leadership for generations, and that it was in the defense of freedom and democracy that Britain in two world wars spent her substance in blood, sweat and tears for the benefit of mankind. In recent years she often seems to have been punished by Fate more for her virtues than her vices. . . .

As already stated, political unity and economic conflict are not reconcilable. Britain and Canada should recognize, however, that the U.S. position as a leading creditor nation in the world is a very complex one owing to her high degree of selfsufficiency. The United Kingdom, when she held that position, required goods from many countries throughout the world. Generally speaking, the U.S.A. does not. The fact remains, however, that, regardless of the internal political implications, the U.S.A. must face up to allowing, in fact to encouraging, the freer entry of British and Western European goods. It is perhaps too much to expect that countries whose economies are being seriously affected by the inaccessibility of the U.S. market should cooperate wholeheartedly with her in the political field. . . .

The problems which are facing the English-speaking world today are so great and so much is at stake that none of us can allow our preoccupations with domestic considerations to lead to deep division of policy between us. . . . Let us, therefore, make no assumption that because we talk alike and share a common heritage and common beliefs in many fundamental truths, we will always think and react alike when difficulties arise. And let our future relations be based on realities rather than on sentimentalities. When we do so our joint action will be established upon a secure foundation.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureFirst Panel Discussion

October 1957 By SIR GEOFFREY CROWTHER -

Feature

FeatureOpening; Assembly

October 1957 By THE HONORABLE LEWIS W. DOUGLAS -

Feature

FeatureFinal Assembly

October 1957 By THE HONORABLE JOHN GEORGE DIEFENBAKER -

Feature

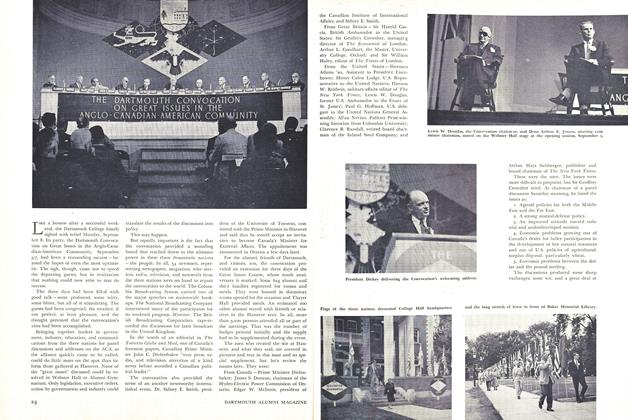

FeatureTHE DARTMOUTH CONVOCATION ON GREAT ISSUES IN THE . ANGLO – CANADIAN – AMERICAN COMMUNITY

October 1957 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

FeatureFirst Panel Discussion

October 1957 By CLARENCE B. RANDALL -

Feature

FeatureHonorary Degree Ceremony

October 1957 By SIR WILLIAM HALEY

Features

-

Feature

FeatureTimbers Heads Alumni Council

JULY 1969 -

Feature

FeatureCleaning Up La

JUNE 1997 By Jim Newton '85 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Ten-Year Report By the Thirteenth President

June 1980 By John G. Kemeny -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

Mar/Apr 2013 By JOHN SHERMAN, JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureA Place In the Country

January 1975 By KENNETH A. JOHNSON -

Feature

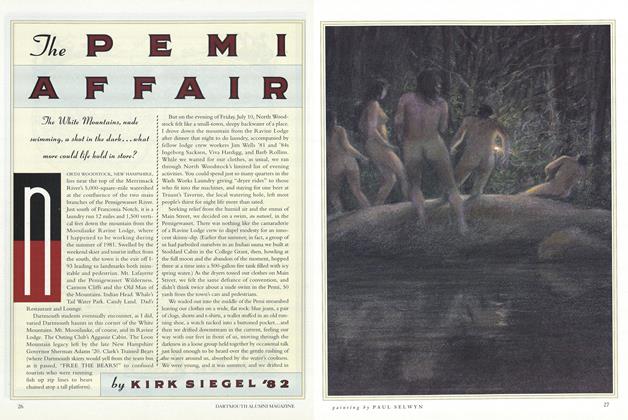

FeatureTHE PEMI AFFAIR

June 1993 By KIRK SIEGEL'82