The following talk was given by Thomas C. Seawell '59 of Denver, Colo., at the annual Christmas luncheon of the Dartmouth Association of the Great Divide, held in Denver on December 20 and attended by some 180 alumni, undergraduates, Dartmouth fathers, and prospective students from the area's secondary schools. The club officers thought it so fine that they persuaded Seawell to write out his talk, given from notes, and then submitted it to the ALUMNI MAGAZINE, which is happy to print such an outstanding undergraduate statement.

Thirst of all, I would like to say how honored I am to be given the opportunity to speak before this group. When Paul Clarkin asked me to speak, he said he'd like to have me talk for five or ten minutes on what Dartmouth means to me, as a senior, and I felt quite inadequate to that task. I remembered the men who had spoken before me as I sat in this same room - Monte Pascoe, two years ago, and last year, my good friend Joe Blake, who is in the audience today - and I knew that filling their shoes would be no small job. With these thoughts in mind, I turned to Dartmouth for help, as I have done so many times in the past; and as usual, } found the help I needed.

As I looked over the Dartmouth seal, I noticed the motto that appears on every Dartmouth crest: "Vox clamantis in deserto," a voice crying in the wilderness. It occurred to me that perhaps never before has this motto had such tremendous significance as it has today, for I believe that we are now living in a terrifying wilderness. The wilderness of which I speak is a wilderness of microscopes, test tubes, intercontinental missiles and the like; in short, it is the wilderness of science.

I am well aware of the advantages of science and the many wonderful products and inventions it has given us: products without which most of us could hardly get along. To mention a few, it has given us the automobile and many other forms of transportation, and it has given us the ability to unleash previously unknown sources of nuclear energy; for these gifts any man should be truly grateful. Yet never before in our history have several hundred Americans died in a single weekend on our nation's highways; and never in the history of the world have over 45,000 human beings met their death in a matter of minutes in a single city as they did in the early days of August 1945. If these are the results of a scientific age then I am skeptical as to the real value of science.

In his book, Brave New World, the novelist Aldous Huxley portrayed a world in which the mind and body of every man was completely controlled by scientific methods and discoveries. It was, I believe, a horrifying picture indeed. As I'm sure you know, Mr. Huxley has recently finished a new book called Brave NewWorld Revisited, and in this work he sees the world which he prophesied some twenty years ago even closer than he had previously thought it would be. I personally cannot take this artistic foreshadowing too lightly; I believe Mr. Huxley's predictions are distressingly accurate.

As I drove home from Boulder a few days ago - as some of you know, I have certain ties in Boulder which have kept me on the road quite a bit this last week - the radio program to which I was listening was interrupted by a special news bulletin announcing the successful launching of an Atlas missile weighing over four tons. At the end of the bulletin, the disc jockey broke out with some words which I shall never forget: "Did you hear that, Mom? We finally beat those Russians!" The only thought that came to me was, "What kind of a victory is that?" Just who are these Russians that any sort of a victory over them is the most important thing in our lives? It seems to me that a victory over such vulgar materialism - at least a victory which is itself materialistic - is hardly a victory at all. Gentlemen, if we commit ourselves to these ideals we are selling out, and at such a cheap, cheap price indeed. I am not convinced that a dishonorable victory is better than an honorable defeat, if such defeat is necessary.

This, then, is the wilderness in which I believe the voice of the Dartmouth man is crying: a world in which each man's mind is dominated by science. I firmly believe that science can and should be an extremely fruitful means to certain proper ends, but it must never be considered an end in itself.

But Dartmouth offered more help to me while I was trying to decide what to say today. I remembered the lone pine tree which now stands symbolically on the top of Baker Tower and which every Dartmouth man carries in his heart. The pine tree, I believe, is one of Dartmouth's most meaningful symbols, and I would like to explain what it symbolizes to me.

As you know, the pine tree is a unique tree in many ways. It is the only tree in the forest that remains firm and stately over the passage of time. It does not lose its leaves with the changing seasons as do the other trees. It is not torn or rent by the icy blasts of winter, its limbs are not broken by the heavy snows, and its roots are not washed away by the rains of spring and summer. No, throughout all these hardships the pine retains its unchanging majesty and beauty. And it is towards building men with the same qualities as those of the pine tree that Dartmouth is dedicated. The Dartmouth man, educated in the liberal arts, is a man who will not be buffeted about by the harsh winds of ill fortune, who will not be broken by the snows of propaganda and whose roots are much too deep to be washed away by the rains of gold and silver which come and go. He is a man who is close to Nature and who is intimately acquainted with the Arts. A liberal arts education could hardly be called pragmatic or practical, for in itself it will not make a single dollar for you. Rather, it's an intangible quality which each Dartmouth man pulls into himself with the most passionate inwardness.

I recently had the pleasure of reading something written some thirty years ago by a man who is today probably better known for his legal abilities than his literary activities. He is a man with whom I've had the closest and most intimate of all relationships for the past twenty-one, almost twenty-two years, and I would like to quote a brief passage from his work because he expresses far better than I can the real value of a liberal arts education:

"The man educated in the liberal arts appreciates the beauty of friendship and confidence, and binds his friends to himself with hoops of steel, and they are to him his most priceless possessions. And perhaps greatest of all, he has the perfect repose of a mind which lives in itself while it lives in the world, and which has ample resources of its own for happiness at home, when it cannot go abroad; and he has an inherent gift, without which good fortune is vulgar, and with which, failure and disappointment meet a charm."

This, the liberal arts education, is what Dartmouth offers you, and it is the education which every man not only deserves but needs so much.

At Dartmouth you will become a part of an active and energetic community, a community made up of men who will be your equals in every respect. You will learn the value of friendship based on integrity and common pursuits and interests in life. When you graduate, you will cherish the memories you will take with you, and you will become a man deeply immersed in the sea of humanity. Mere pity and sympathy will give way to that almost divine quality of deep and true understanding of the problems of your fellow creatures, and you will realize the full meaning of John Donne's immortal words, "No man is an island, entire unto itself."

There undoubtedly are quite a few of you who are planning on scientific vocations, and perhaps I've given you the impression that Dartmouth's doors are closed to you; but on the contrary, I believe just the reverse is true. We have a large number of men who are headed toward careers in the field of science, and of them we are truly proud. Yet, Dartmouth takes care of these men; she makes sure that they are not isolated in the laboratory, but are given a thorough insight into the Arts, Philosophy and Religion. These men gain the full benefit of Dartmouth, and I know that they feel so much better prepared to enter into their futures with the broad perspective of life which only the liberal arts education can give.

I hope I have not been overbearingly serious today, because this luncheon is a happy time toward.which we undergraduates all look forward. After the fall term we've just spent in Hanover, it's a wonderful feeling to have a few weeks of rest and relaxation at home. There are a lot of things which we anxiously anticipate during the fall, and the opportunity which this luncheon affords to see alumni, friends and prospective Dartmouth men is a highly valued one.

To conclude, I would like to sum up what I've tried to say by borrowing the words of one of Dartmouth's immortal sons, Daniel Webster. In the famous Dartmouth College Case, Webster rested his case with the following sentence, which, in my opinion, captures the real essence of every Dartmouth man's feelings: "It's a small college, but there are those who love it."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

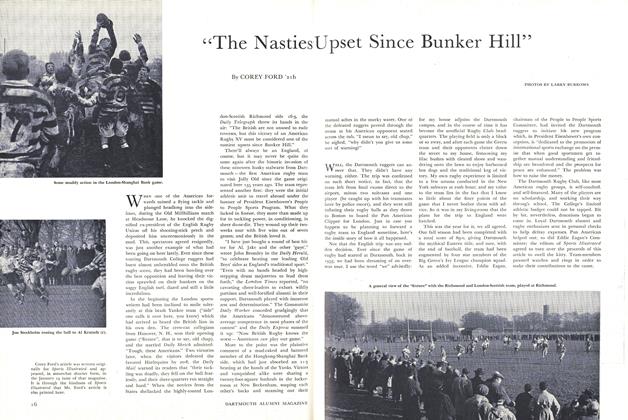

Feature"The Nasties Upset Since Bunker Hill"

February 1959 By COREY FORD '21h -

Feature

FeatureThat Other Dartmouth Carnival

February 1959 By FREDERICK L. BACON '59 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni Council Dinner Honors Football Team

February 1959 -

Feature

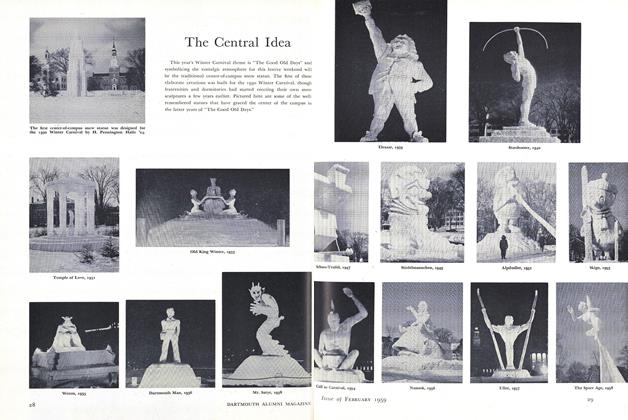

FeatureThe Central Idea

February 1959 -

Article

ArticleSome Consequences of Inflation Psychology

February 1959 By COLIN D. CAMPBELL, -

Article

ArticleShould We Blame the Unions?

February 1959 By MARTIN SEGAL