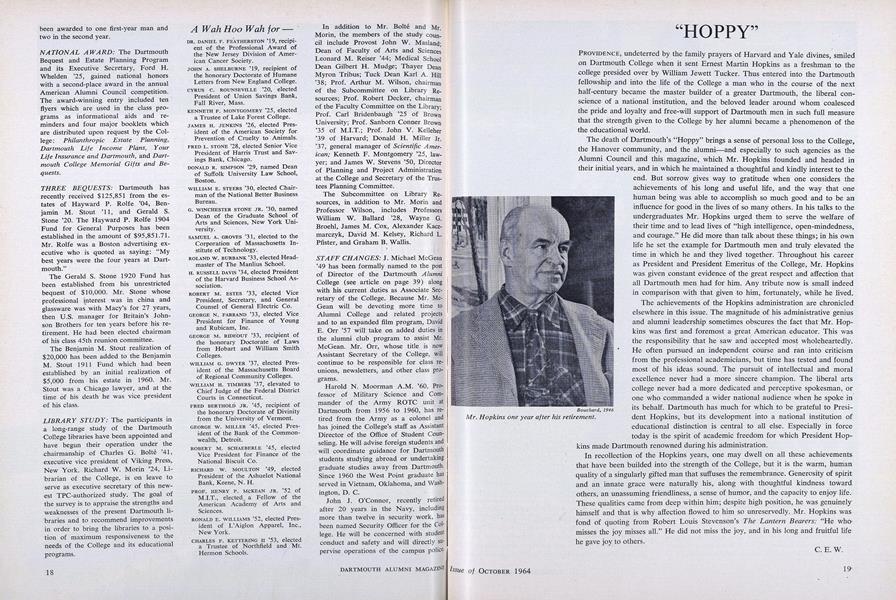

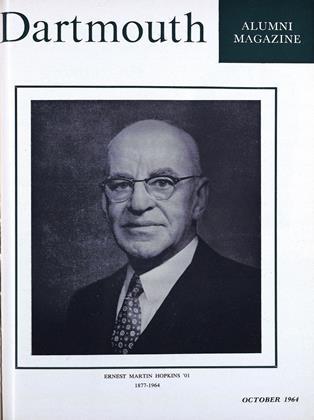

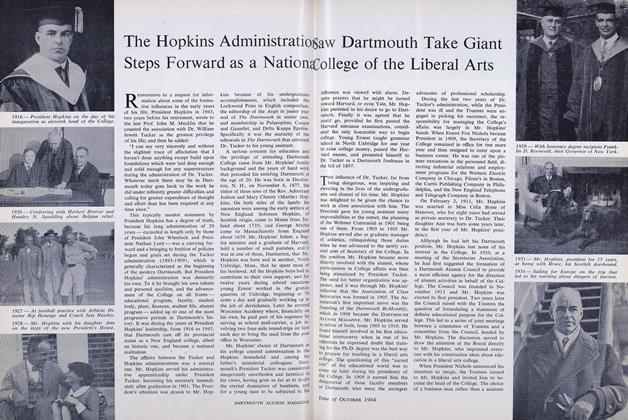

PROVIDENCE, undeterred by the family prayers of Harvard and Yale divines, smiled on Dartmouth College when it sent Ernest Martin Hopkins as a freshman to the college presided over by William Jewett Tucker. Thus entered into the Dartmouth fellowship and into the life of the College a man who in the course of the next half-century became the master builder of a greater Dartmouth, the liberal conscience of a national institution, and the beloved leader around whom coalesced the pride and loyalty and free-will support of Dartmouth men in such full measure that the strength given to the College by her alumni became a phenomenon of the the educational world.

The death of Dartmouth's "Hoppy" brings a sense of personal loss to the College, the Hanover community, and the alumni—and especially to such agencies as the Alumni Council and this magazine, which Mr. Hopkins founded and headed in their initial years, and in which he maintained a thoughtful and kindly interest to the end. But sorrow gives way to gratitude when one considers the achievements of his long and useful life, and the way that one human being was able to accomplish so much good and to be an influence for good in the lives of so many others. In his talks to the undergraduates Mr. Hopkins urged them to serve the welfare of their time and to lead lives of "high intelligence, open-mindedness, and courage." He did more than talk about these things; in his own life he set the example for Dartmouth men and truly elevated the time in which he and they lived together. Throughout his career as President and President Emeritus of the College, Mr. Hopkins was given constant evidence of the great respect and affection that all Dartmouth men had for him. Any tribute now is small indeed in comparison with that given to him, fortunately, while he lived.

The achievements of the Hopkins administration are chronicled elsewhere in this issue. The magnitude of his administrative genius and alumni leadership sometimes obscures the fact that Mr. Hopkins was first and foremost a great American educator. This was the responsibility that he saw and accepted most wholeheartedly. He often pursued an independent course and ran into criticism from the professional academicians, but time has tested and found most of his ideas sound. The pursuit of intellectual and moral excellence never had a more sincere champion. The liberal arts college never had a more dedicated and perceptive spokesman, or one who commanded a wider national audience when he spoke in its behalf. Dartmouth has much for which to be grateful to President Hopkins, but its development into a national institution of educational distinction is central to all else. Especially in force today is the spirit of academic freedom for which President Hopkins made Dartmouth renowned during his administration.

In recollection of the Hopkins years, one may dwell on all these achievements-that have been builded into the strength of the College, but it is the warm, human quality of a singularly gifted man that suffuses the remembrance. Generosity of spirit and an innate grace were naturally his, along with thoughtful kindness toward others, an unassuming friendliness, a sense of humor, and the capacity to enjoy life. These qualities came from deep within him; despite high position, he was genuinely himself and that is why affection flowed to him so unreservedly. Mr. Hopkins was fond of quoting from Robert Louis Stevenson's The Lantern Bearers: "He who misses the joy misses all." He did not miss the joy, and in his long and fruitful life he gave joy to others.

Mr. Hopkins one year after his retirement.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Hopkins Administration Steps Forward as a National

October 1964 -

Feature

FeatureSome Hopkins Views on Higher Education

October 1964 -

Feature

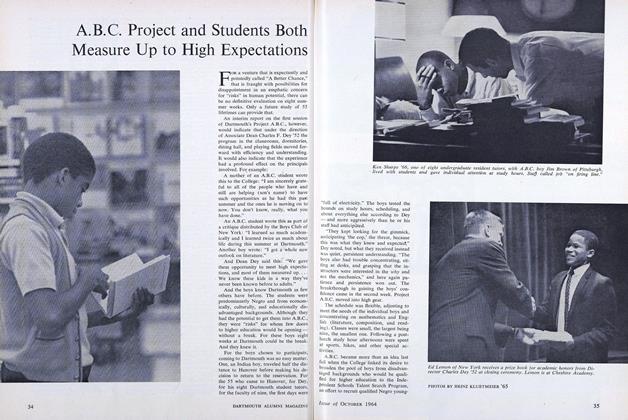

FeatureA.B.C. Project and Students Both Measure Up to High Expectations

October 1964 -

Feature

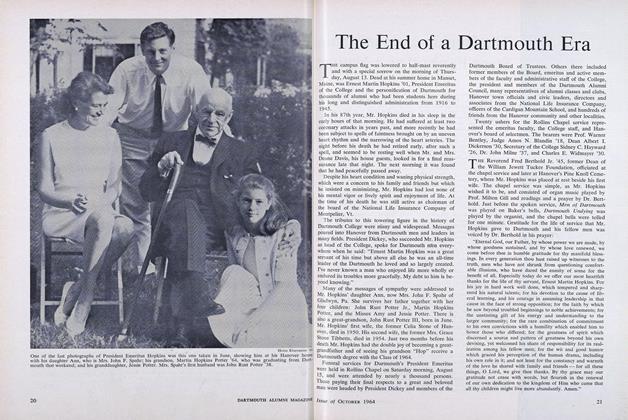

FeatureThe End of a Dartmouth Era

October 1964 -

Feature

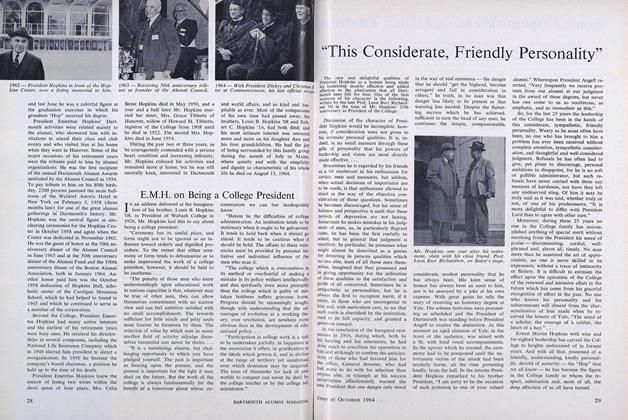

Feature"This Considerate, Friendly Personality"

October 1964 -

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

October 1964 By GEORGE O'CONNELL

C.E.W.

Article

-

Article

ArticleFLORIDA ALUMNI GROUP CLAIMS ALTITUDE RECORD

March, 1926 -

Article

ArticleCLASS ORGANIZATION AND CLASS FINANCES

June 1929 -

Article

ArticleTrustee Decision

February 1977 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth’s Greatest Conservationist

December 1990 By Peter S. Bridges ’53 -

Article

ArticleThe 25th Anniversary

June 1941 By The Editor -

Article

ArticleSTUDENT WAR STRIKE

May 1935 By W. J. Minsch Jr. '36