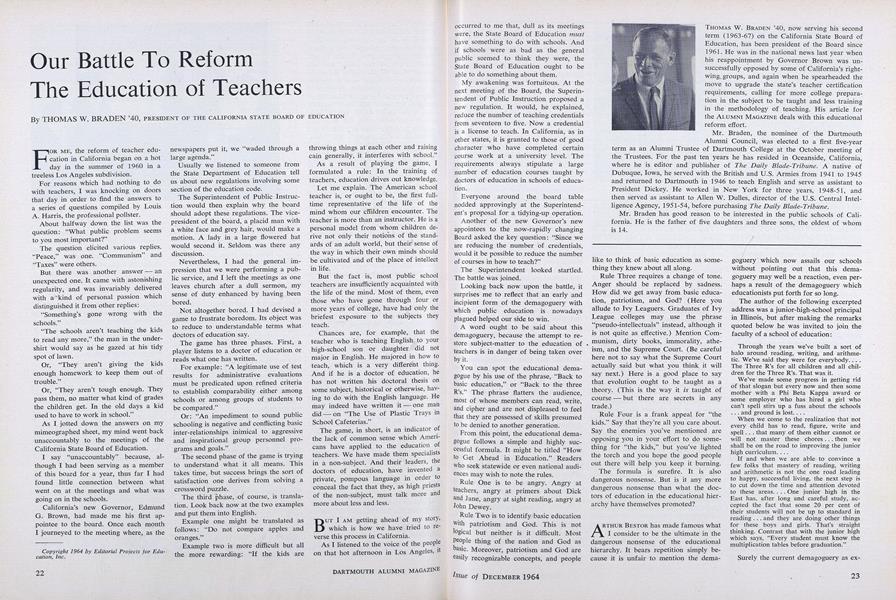

PRESIDENT OF THE CALIFORNIA STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION

FOR ME, the reform of teacher education in California began on a hot day in the summer of 1960 in a treeless Los Angeles subdivision.

For reasons which had nothing to do with teachers, I was knocking on doors that day in order to find the answers to a series of questions compiled by Louis A. Harris, the professional pollster.

About halfway down the list was the question: "What public problem seems to you most important?"

The question elicited various replies. "Peace," was one. "Communism" and "Taxes" were others.

But there was another answer — an unexpected one. It came with astonishing regularity, and was invariably delivered with a "kind of personal passion which distinguished it from other replies:

"Something's gone wrong with the schools."

"The schools aren't teaching the kids to read any more," the man in the undershirt would say as he gazed at his tidy spot of lawn.

Or, "They aren't giving the kids enough homework to keep them out of trouble."

Or, "They aren't tough enough. They pass them, no matter what kind of grades the children get. In the old days a kid used to have to work in school."

As I jotted down the answers on my mimeographed sheet, my mind went back unaccountably to the meetings of the California State Board of Education.

I say "unaccountably" because, although I had been serving as a member of this board for a year, thus far I had found little connection between what went on at the meetings and what was going on in the schools.

California's new Governor, Edmund G. Brown, had made me his first appointee to the board. Once each month I journeyed to the meeting where, as the newspapers put it, we "waded through a large agenda."

Usually we listened to someone from the State Department of Education tell us about new regulations involving some section of the education code.

The Superintendent of Public Instruction would then explain why the board should adopt these regulations. The vice-president of the board, a placid man with a white face and grey hair, would make a motion. A lady in a large flowered hat would second it. Seldom, was there any discussion.

Nevertheless, I had the general impression that we were performing a public service, and I left the meetings as one leaves church after a dull sermon, my sense of duty enhanced by having been bored.

Not altogether bored. I had devised a game to frustrate boredom. Its object was to reduce to understandable terms what doctors of education say.

The game has three phases. First, a player listens to a doctor of education or reads what one has written.

For example: "A legitimate use of test results for administrative evaluations must be predicated upon refined criteria to establish comparability either among schools or among groups of students to be compared."

Or: "An impediment to sound public schooling is negative and conflicting basic inter-relationships inimical to aggressive and inspirational group personnel programs and goals."

The second phase of the game is trying to understand what it all means. This takes time, but success brings the sort of satisfaction one derives from solving a crossword puzzle.

The third phase, of course, is translation. Look back now at the two examples and put them into English.

Example one might be translated as follows: "Do not compare apples and oranges."

Example two is more difficult but all the more rewarding: "If the kids are throwing things at each other and raising cain generally, it interferes with school."

As a result of playing the game, I formulated a rule: In the training of teachers, education drives out knowledge.

Let me explain. The American school teacher is, or ought to be, the first full-time representative of the life of the mind whom our children encounter. The teacher is more than an instructor. He is a personal model from whom children derive not only their notions of the standards of an adult world, but their sense of the way in which their own minds should be cultivated and of the place of intellect in life.

But the fact is, most public school teachers are insufficiently acquainted with the life of the mind. Most of them, even those who have gone through four or more years of college, have had only the briefest exposure to the subjects they teach.

Chances are, for example, that the teacher who is teaching English to your high-school son or daughter did not major in English. He majored in how to teach, which is a very different thing. And if he is a doctor of education, he has not written his doctoral thesis on some subject, historical or otherwise, having to do with the English language. He may indeed have written it - one man did — on "The Use of Plastic Trays in School Cafeterias."

The game, in short, is an indicator of the lack of common sense which Americans have applied to the education of teachers. We have made them specialists in a non-subject. And their leaders, the doctors of education, have invented a private, pompous language in order to conceal the fact that they, as high priests of the non-subject, must talk more and more about less and less.

BUT I AM getting ahead of my story, which is how we have tried to reverse this process in California.

As I listened to the voice of the people on that hot afternoon in Los Angeles, it occurred to me that, dull as its meetings were, the State Board of Education must have something to do with schools. And if schools were as bad as the general public seemed to think they were, the State Board of Education ought to be able to do something about them.

My awakening was fortuitous. At the next meeting of the Board, the Superintendent of Public Instruction proposed a new regulation. It would, he explained, reduce the number of teaching credentials from seventeen to five. Now a credential is a license to teach. In California, as in other states, it is granted to those of good character who have completed certain course work at a university level. The requirements always stipulate a large number of education courses taught by doctors of education in schools of education.

Everyone around the board table nodded approvingly at the Superintend-nt's proposal for a tidying-up operation.

Another of the new Governor's new appointees to the now-rapidly changing Board asked the key question: "Since we are reducing the number of credentials, would it be possible to reduce the number of courses in how to teach?"

The Superintendent looked startled. The battle was joined.

Looking back now upon the battle, it surprises me to reflect that an early and incipient form of the demagoguery with which public education is nowadays plagued helped our side to win.

A word ought to be said about this demagoguery, because the attempt to restore subject-matter to the education of teachers is in danger of being taken over by it.

You can spot the educational dema- gogue by his use of the phrase, "Back to basic education," or "Back to the three R's." The phrase flatters the audience, most of whose members can read, write, and cipher and are not displeased to feel that they are possessed of skills presumed to be denied to another generation.

From this point, the educational demagogue follows a simple and highly successful formula. It might be titled "How to Get Ahead in Education." Readers who seek statewide or even national audiences may wish to note the rules.

Rule One is to be angry. Angry at teachers, angry at primers about Dick and Jane, angry at sight reading, angry at John Dewey.

Rule Two is to identify basic education with patriotism and God. This is not logical but neither is it difficult. Most People thing of the nation and God as basic. Moreover, patriotism and God are easily recognizable concepts, and people like to think of basic education as something they knew about all along.

Rule Three requires a change of tone. Anger should be replaced by sadness. How did we get away from basic education, patriotism, and God? (Here you allude to Ivy Leaguers. Graduates of Ivy League colleges may use the phrase "pseudo-intellectuals" instead, although it is not quite as effective.) Mention Communism, that evolution ought to be taught as a theory. (This is the way it is taught of course - but there are secrets in any trade.)

Rule Four is a frank appeal for "the kids." Say that they're all you care about. Say the enemies you've mentioned are opposing you in your effort to do something for "the kids," but you've lighted the torch and you hope the good people out there will help you keep it burning.

The formula is surefire. It is also dangerous nonsense. But is it any more dangerous nonsense than what the doctors of education in the educational hierarchy have themselves promoted?

ARTHUR BESTOR has made famous what L I consider to be the ultimate in the dangerous nonsense of the educational hierarchy. It bears repetition simply because it is unfair to mention the demagoguery which now assails our schools without pointing out that this demagoguery may well be a reaction, even perhaps a result of the demagoguery which educationists put forth for so long.

The author of the following excerpted address was a junior-high-school principal in Illinois, but after making the remarks quoted below he was invited to join the faculty of a school of education:

Through the years we've built a sort of halo around reading, writing, and arithmetic. We've said they were for everybody.... The Three R's for all children and all children for the Three R's. That was it.

We've made some progress in getting rid of that slogan but every now and then some mother with a Phi Beta Kappa award or some employer who has hired a girl who can't spell stirs up a fuss about the schools ... and ground is lost....

When we come to the realization that not every child has to read, figure, write and spell... that many of them either cannot or will not master these chores ... then we shall be on the road to improving the junior high curriculum....

If and when we are able to convince a few folks that mastery of reading, writing and arithmetic is not the one road leading to happy, successful living, the next step is to cut down the time and attention devoted to these areas.... One junior high in the East has, after long and careful study, accepted the fact that some 20 per cent of their students will not be up to standard in reading ... and they are doing other things for these boys and girls. That's straight thinking. Contrast that with the junior high which says, "Every student must know the multiplication tables before graduation."

Surely the current demagoguery as exemplified in the formula for "How to Get Ahead in Basic Education" is no more dangerous nonsense than this. Perhaps the assault on public education in California, Texas, and other states represents a kind of reverse justice. Those who perpetrated dangerous nonsense are now being treated to dangerous nonsense in return. A school system which failed to educate children is reaping the penalty.

To reform teacher education in California, we took advantage of the reverse demagoguery. We could not help it. It existed in the minds of people as they thought about education, although none of us who fought the battle ever used the phrase, "Back to the Three R's."

Even so, it took two years to put subject matter into teacher education. It took the strong arm of a Governor who was willing to risk the opposition of a powerful educationist lobby. It took a bill in the legislature. It took a strong state senator chosen by the State Board to carry the bill. When, despite his best efforts, the educationist lobby succeeded in compromising it into virtual ineffectuality, it was saved by a last-minute ruse: the state senator won the agreement of the educationist lobby on a sentence in the bill which permitted the State Board of Education to spell out the actual hours of course work to be required of teacher candidates.

The educationist lobby accepted this proposal because its members thought the result might be less drastic than legislation. After all, they must have reasoned, a State Board of Education usually does what educators want it to do. No doubt, the Board would turn over the actual writing of the regulations to a committee of doctors of education who understood these matters.

We did not. Instead, we did something quite revolutionary. The moment the bill was passed, we sat down and wrote the regulations ourselves.

It was a long and arduous task performed on successive weekends by men and women who had many other things to do and who were not, after all, well-versed in the intricacies of teacher credentials, credits, transfers, semester hours, and course work.

"Never mind," we said to each other. "If we turn it over to a committee of educators, we may as well give up reform."

And so we learned the intricacies and we wrote the regulations amidst much comment from the educationists about "the ridiculousness of lay boards writing regulations."

There were, to be sure, some embarrassing moments.

I remember, for example, a meeting of doctors of education who had asked me to state the Board's side of the argument.

I gave a short talk saying what any man who graduated from a four-year liberal arts college might be expected to say. After listing the principal areas of knowledge - science, mathematics, language, history, and the fine arts - I explained that I thought all other subjects were derivative. I said the Board would look with a jaundiced eye on such hyphenated college courses as business-English and on such substitutes for the language requirement as radio broadcasting, journalism, and stagecraft.

Finally I pointed out that the legislation itself specifically barred education as an academic course and I confessed that I thought this was a good thing. Teachers, I said, who majored in one of the principal branches of learning or in derivatives of one of these branches knew more about what was important than teachers who majored in education.

When I had finished, the Dean of the Education Department of one of California's largest private institutions of learning rose from the back row.

"I have," he said, "been training teachers for thirty years. Would you mind telling me your experience in this field?"

Nevertheless, we went ahead. The public accepted the new regulations. The teachers did, too. Only the doctors of education who teach courses in education are still in active opposition, and understandably so.

Under the new law and the new regulations, no teacher in California may teach any subject in which he has not majored or minored. Either the major or the minor must be in academic subject-matter, as defined by the Board of Education. Those who want to be administrators must possess an academic major.

The change was drastic. Until we wrote and enacted our own regulations, teacher trainees in California were forced by schools of education to spend nearly 50 per cent of their college time taking courses in how to teach. Under reform, this trade training is reduced to 13 per cent for elementary teachers and to 9 per cent for those who want to teach secondary grades. Since most students who want to be teachers want also to leave the door open for advancement to administrative posts, it is logical to assume that they will choose an academic major from now on.

In effect, the new law and the new regulations mean that very few college students in California will major in education. No wonder educationists are still fighting the reform.

They have proposed, in some of our state colleges, to get around reform by labeling courses in education as something else. "Philosophy of Education," for example, could be labeled "Philosophy. When this fails, as I believe it will, they may try to deny graduation to prospective students who take only the minimum number of courses in education as prescribed by the new regulations.

When this fails, too, as I think it will, they will probably go back to the legislature and wage the battle again, citing their vast experience in training teachers.

We shall have to fight them by pointing out that their vast experience in training teachers is what is wrong with our schools.

FOR AS I REFLECT on what we are trying to do in California, it seems to me that teacher training by doctors of education is precisely what is wrong with our schools and that the evidence is everywhere to be seen.

Our children are taught mathematics by teachers who majored in how to teach. They are taught physics, chemistry, government, history, geography - and even physical education — by teachers who majored in how to teach.

The courses which are taught in our how-to-teach colleges should frighten any parent. Consider, for example, a course in consumer economics at a California college devoted principally to the education of teachers. It is described in the catalog as follows: "American standards of living and culture, comparative standards of living, the economics of consumption, consumer problems. (Meets the State safety and fire prevention requirements.)"

Or consider a course in administration taught at a similar institution. It is described in the catalog in the following manner: "In this course are considered the usual problems which are considered in a course of this kind."

There is other evidence. There is the evidence of children who do not care much about reading. There is the evidence of teachers who hesitate to state their opinions, partly'because they are ill-paid and insecure but also because they lack the confidence of knowledge.

There is evidence in the surprising youth of the hate groups which have flowered recently in California and else-where. Surely there must be some relationship between the quality of our edu- cation and the demonstrable fact that a noisy percentage of young Americans have somehow managed to go through school without ever learning enough about ideas to be able to tolerate them.

Finally, it seems to me the evidence is in the tendency of the public schools to adopt the spirit of "I'm as good as Nancy."

"I'm as good as Nancy" is what my daughter Susan says about her report card. Susan is in the third grade. She is the prettiest of my five daughters, the only one of whom I can say with confidence that if she keeps her wits about her, she will marry well.

But what are her wits?

In reading she gets a check mark, in spelling a check mark, in geography a check mark. Her whole report card is a series of check marks and the teacher comments at the end that "Susan has joined us in many interesting group activities."

Now I happen to know that Susan cannot read. She reads much less readily than does her sister Nancy who is a year younger. But when I point this out to Susan she says, "I'm as good as Nancy." She can produce the check mark on her report card against the check mark on Nancy's report card to prove her point.

I suppose the reason for the check marks is to make Susan feel happy, secure, and adjusted.

I sympathize with this aim because I love Susan very much. But these check marks tend to fool Susan and to fool a parent, too. I do not wish to be made to feel happy, secure, and adjusted about Susan. I wish only to know how badly she is reading in comparison with her peers and, if possible, why.

In other words, I put learning before adjustment. The school, it seems to me, puts adjustment before learning.

Perhaps I am wrong in blaming this on doctors of education. But they have been in charge of our schools for a long time and I do not know who else can be blamed.

A hundred years ago Alexis de Tocqueville made a study of the American democracy. De Tocqueville liked America; he liked our industriousness; he thought it wonderful that this new land should be producing great leaders who did not spring from an entrenched aristocracy. But there was something about America that was disturbing, disquieting, to de Tocqueville. He thought it possible that we might eventually confuse liberty with equality, and he predicted that if we made this mistake, it would be our downfall.

I think we are already making it and that the best example of our confusion is evidenced in the spirit of "I'm as good as Nancy."

When our schools adopt the theory that learning is less important than some other objective - that adjustment is more important, or happiness is more important (as though happiness could be achieved without accomplishment), when they do not provide the exciting stimulus of the surmountable task, or designate by grades and merits those who excel and those who do not, we shall reach a state of utter confusion between democracy and equality. We shall bring up a generation in which everybody is as good as anybody and nobody achieves anything at all.

We have tried in California to halt this process. At least in the training of teachers, which is where learning begins, we have tried to put learning in first place.

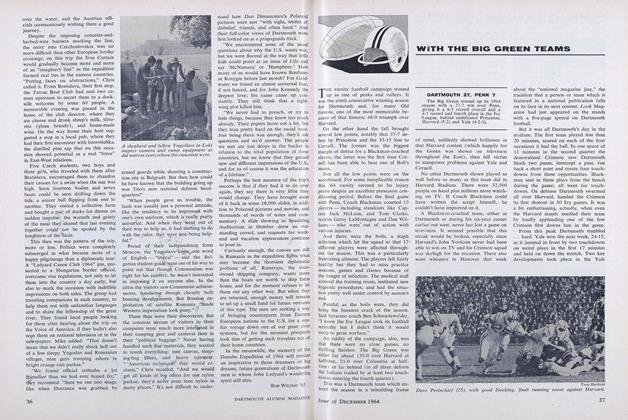

Dartmouth's team (right foreground) shown with nine others from Canada and theU. S. competing in the 9th annual Intercollegiate Game Fish Seminar and FishingMatch off Wedgeport, Nova Scotia, over Labor Day weekend. New Brunswick won,followed by Western Ontario, Yale, Dartmouth, Princeton, Dalhousie, Harvard, St.Francis Xavier, U. of Mass., and Toronto. The Dartmouth team (l to r): DaveOwens '66, Paul Murphy '66, Bill Rutledge '66, Coach Jim Schwedland '48, Capt.Dave Hazelton '65, and Ted Talbot '65.

Copyright 1964 by Editorial Projects for Education, Inc.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureVANISHING ABSOLUTES

December 1964 -

Feature

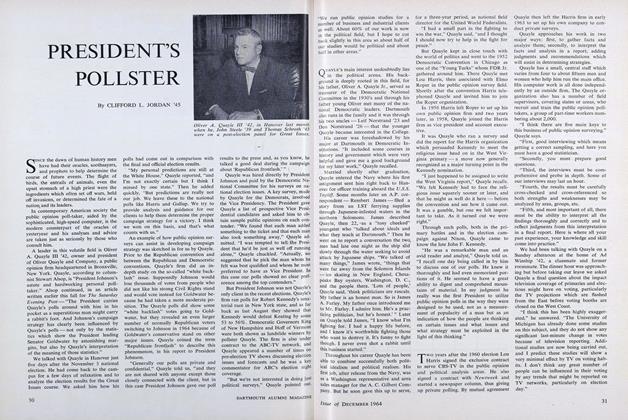

FeaturePRESIDENT'S POLLSTER

December 1964 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

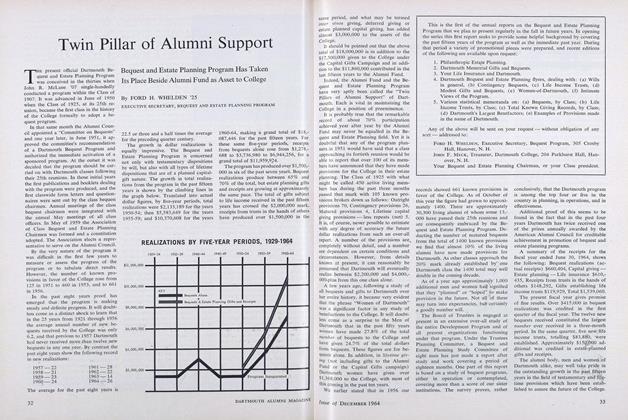

FeatureTwin Pillar of Alumni Support

December 1964 By FORD H. WHELDEN '25 -

Feature

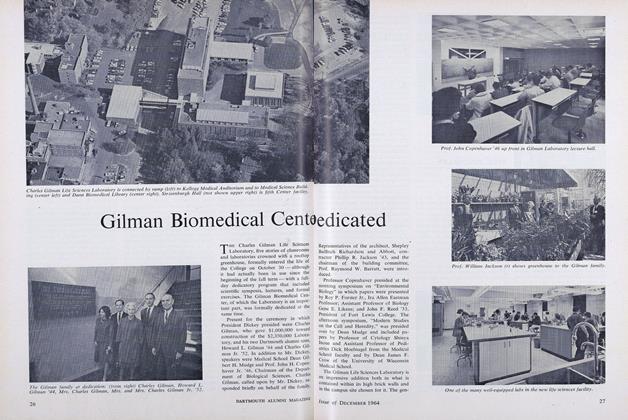

FeatureGilman Biomedical Centedicated

December 1964 -

Article

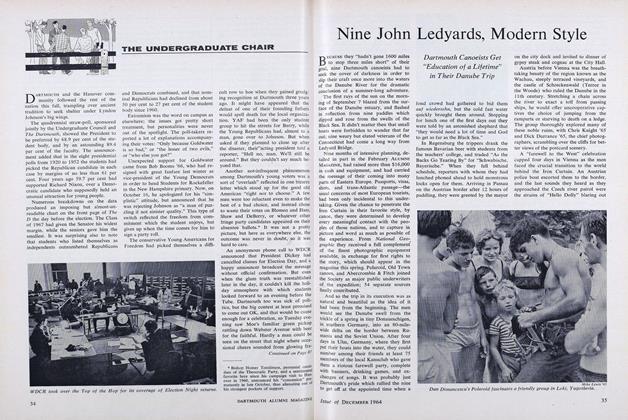

ArticleNine John Ledyards, Modern Style

December 1964 By BOB WILDAU '65 -

Article

ArticleWITH THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

December 1964

THOMAS W. BRADEN '40

-

Article

ArticleJohn M. Mecklin, Teacher

May 1940 By Thomas W. Braden '40 -

Article

ArticleAutumn Days

November 1946 By Thomas W. Braden '40 -

Article

ArticleA Clear Line

February 1947 By Thomas W. Braden '40 -

Article

ArticleA Popularity Poll

April 1947 By Thomas W. Braden '40 -

Books

BooksINDIRECTIONS

April 1947 By Thomas W. Braden '40 -

Article

ArticleThe Freedom to Choose

OCT. 1977 By THOMAS W. BRADEN '40

Features

-

Cover Story

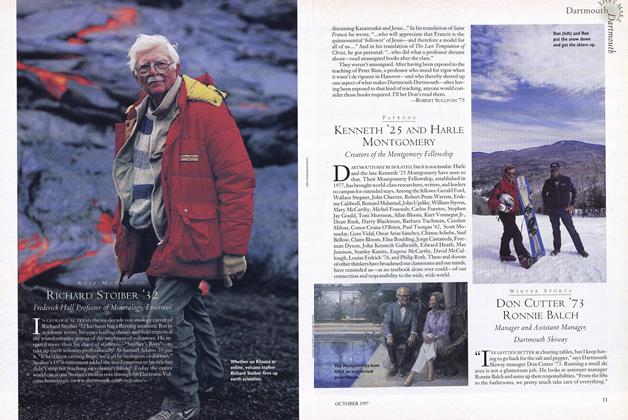

Cover StoryRichard Stoiber '32

OCTOBER 1997 -

Feature

FeatureA Change in the Weather

APRIL 1998 -

Feature

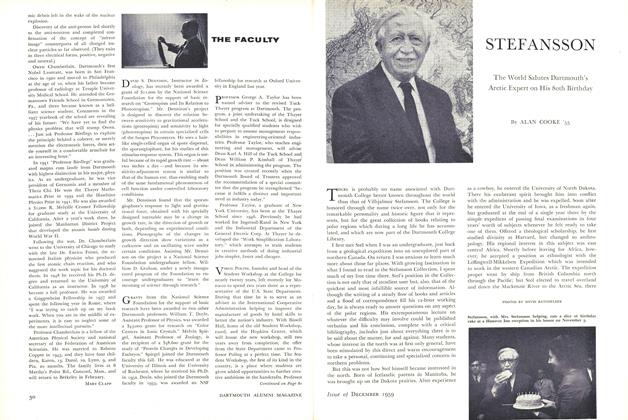

FeatureSTEFANSSON

December 1959 By ALAN COOKE '55 -

Feature

FeatureInnocence Lost

Jan/Feb 2002 By DOUGLAS RAYBECK '64 -

Feature

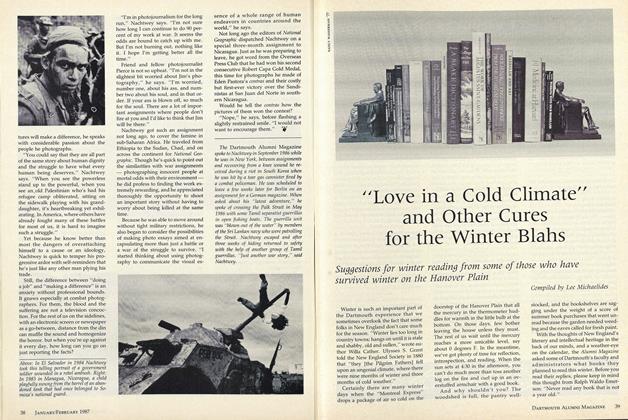

Feature"Love in a Cold Climate" and Other Cures for the Winter Blahs

JANUARY/FEBRUARY • 1987 By Lee Michaelides -

FEATURES

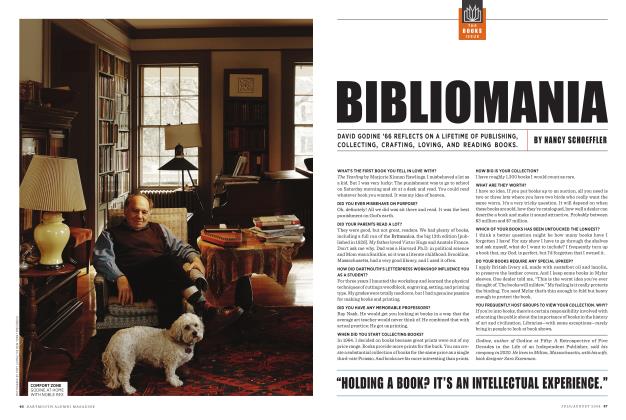

FEATURESBibliomania

JULY | AUGUST 2024 By NANCY SCHOEFFLER