SINCE the dawn of human history men have had their oracles, soothsayers, and prophets to help determine the course of future events. The flight of birds, the entrails of animals, even the upset stomach of a high priest were the ingredients which often set off wars, held off invasions, or determined the fate of a nation and its leaders.

In contemporary American society the public opinion poll-taker, aided by the sophisticated, high-speed computer, is the modern counterpart of the oracles of yesteryear and his analyses and advice are taken just as seriously by those who consult him.

A leader in this volatile field is Oliver A. Quayle III '42, owner and president of Oliver Quayle and Company, a public opinion firm headquartered in Bronxville, New York. Quayle, according to columnist Stewart Alsop, is "President Johnson's astute and hardworking personal polltaker." Alsop continued, in an article written earlier this fall for The SaturdayEvening Post - "The President carries Quayle's polls around with him in his pocket as a superstitious man might carry a rabbit's foot. And Johnson's campaign strategy has clearly been influenced by Quayle's polls - not only by the statistics which show the President leading Senator Goldwater by astonishing margins, but also by Quayle's interpretation of the meaning of those statistics."

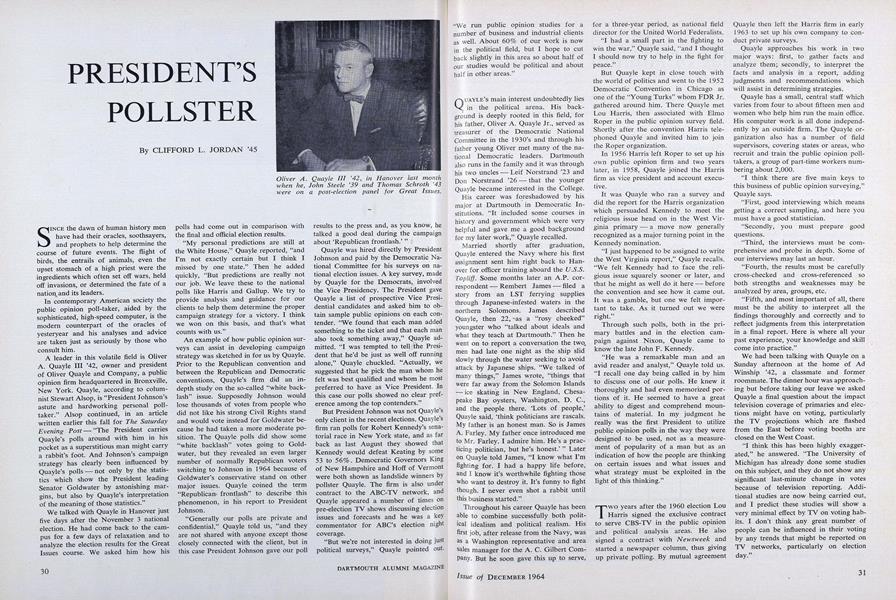

We talked with Quayle in Hanover just five days after the November 3 national election. He had come back to the campus for a few days of relaxation and to analyze the election results for the Great Issues course. We asked him how his polls had come out in comparison with the final and official election results.

"My personal predictions are still at the White House," Quayle reported, "and I'm not exactly certain but I think I missed by one state." Then he added quickly, "But predictions are really not our job. We leave these to the national polls like Harris and Gallup. We try to provide analysis and guidance for our clients to help them determine the proper campaign strategy for a victory. I think we won on this basis, and that's what counts with us."

An example of how public opinion surveys can assist in developing campaign strategy was sketched in for us by Quayle. Prior to the Republican convention and between the Republican and Democratic conventions, Quayle's firm did an indepth study on the so-called "white backlash" issue. Supposedly Johnson would lose thousands of votes from people who did not like his strong Civil Rights stand and would vote instead for Goldwater because he had taken a more moderate position. The Quayle polls did show some "white backlash" votes going to Goldwater, but they revealed an even larger number of normally Republican voters switching to Johnson in 1964 because of Goldwater's conservative stand on other major issues. Quayle coined the term "Republican frontlash" to describe this phenomenon, in his report to President Johnson.

"Generally our polls are private and confidential," Quayle told us, "and they are not shared with anyone except those closely connected with the client, but in this case President Johnson gave our poll results to the press and, as you know, he talked a good deal during the campaign about 'Republican frontlash.' "

Quayle was hired directly by President Johnson and paid by the Democratic National Committee for his surveys on national election issues. A key survey, made by Quayle for the Democrats, involved the Vice Presidency. The President gave Quayle a list of prospective Vice Presidential candidates and asked him to obtain sample public opinions on each contender. "We found that each man added something to the ticket and that each man also took something away," Quayle admitted. "I was tempted to tell the President that he'd be just as well off running alone," Quayle chuckled. "Actually, we suggested that he pick the man whom he felt was best qualified and whom he most preferred to have as Vice President. In this case our polls showed no clear preference among the top contenders."

But President Johnson was not Quayle's only client in the recent elections. Quayle's firm ran polls for Robert Kennedy's senatorial race in New York state, and as far back as last August they showed that Kennedy would defeat Keating by some 53 to 56%. Democratic Governors King of New Hampshire and Hoff of Vermont were both shown as landslide winners by pollster Quayle. The firm is also under contract to the ABC-TV network, and Quayle appeared a number of times on pre-election TV shows discussing election issues and forecasts and he was a key commentator for ABC's election night coverage.

"But we're not interested in doing just political surveys," Quayle pointed out. "We run public opinion studies for a number of business and industrial clients as well. About 60% of our work is now in the political field, but I hope to cut back slightly in this area so about half of our studies would be political and about half in other areas."

QUAYLE'S main interest undoubtedly lies in the political arena. His background is deeply rooted in this field, for his father, Oliver A. Quayle Jr., served as treasurer of the Democratic National Committee in the 1930's and through his father young Oliver met many of the national Democratic leaders. Dartmouth also runs in the family and it was through his two uncles - Leif Norstrand '23 and Don Norstrand '26 - that the younger Quayle became interested in the College.

His career was foreshadowed by his major at Dartmouth in Democratic Institutions. "It included some courses in history and government which were very helpful and gave me a good background for my later work," Quayle recalled.

Married shortly after graduation, Quayle entered the Navy where his first assignment sent him right back to Hanover for officer training aboard the U.S.S.Topliff. Some months later an A.P. correspondent - Rembert James - filed a story from an LST ferrying supplies through Japanese-infested waters in the northern Solomons. James described Quayle, then 22, -as a "rosy cheeked" youngster who "talked about ideals and what they teach at Dartmouth." Then he went on to report a conversation the two. men had late one night as the ship slid slowly through the water seeking to avoid attack by Japanese ships. "We talked of many things," James wrote, "things that were far away from the Solomon Islands - ice skating in New England, Chesapeake Bay oysters, Washington, D. C., and the people there. 'Lots of people,' Quayle said, 'think politicians are rascals. My father is an honest man. So is James A. Farley. My father once introduced me to Mr. Farley. I admire him. He's a practicing politician, but he's honest.' " Later on Quayle told James, "I know what I'm fighting for. I had a happy life before, and I know it's worthwhile fighting those who want to destroy it. It's funny to fight though. I never even shot a rabbit until this business started."

Throughout his career Quayle has been able to combine successfully both political idealism and political realism. His first job, after release from the Navy, was as a Washington representative and area sales manager for the A. C. Gilbert Company. But he soon gave this up to serve, for a three-year period, as national field director for the United World Federalists.

"I had a small part in the fighting to win the war," Quayle said, "and I thought I should now try to help in the fight for peace."

But Quayle kept in close touch with the world of politics and went to the 1952 Democratic Convention in Chicago as one of the "Young Turks" whom FDR Jr. gathered around him. There Quayle met Lou Harris, then associated with Elmo Roper in the public opinion survey field. Shortly after the convention Harris telephoned Quayle and invited him to join the Roper organization.

In 1956 Harris left Roper to set up his own public opinion firm and two years later, in 1958, Quayle joined the Harris firm as vice president and account executive.

It was Quayle who ran a survey and did the report for the Harris organization which persuaded Kennedy to meet the religious issue head on in the West Virginia primary - a move now generally recognized as a major turning point in the Kennedy nomination.

"I just happened to be assigned to write the West Virginia report," Quayle recalls. "We felt Kennedy had to face the religious issue squarely sooner or later, and that he might as well do it here — before the convention and see how it came out. It was a gamble, but one we felt important to take. As it turned out we were right."

Through such polls, both in the primary battles and in the election campaign against Nixon, Quayle came to know the late John F. Kennedy.

"He was a remarkable man and an avid reader and analyst," Quayle told us. "I recall one day being called in by him to discuss one of our polls. He knew it thoroughly and had even memorized portions of it. He seemed to have a great ability to digest and comprehend mountains of material. In my judgment he really was the first President to utilize public opinion polls in the way they were designed to be used, not as a measurement of popularity of a man but as an indication of how the people are thinking on certain issues and what issues and what strategy must be exploited in the light of this thinking."

Two years after the 1960 election Lou Harris signed the exclusive contract to serve CBS-TV in the public opinion and political analysis areas. He also signed a contract with Newsweek and started a newspaper column, thus giving up private polling. By mutual agreement Quayle then left the Harris firm in early 1963 to set up his own company to conduct private surveys.

Quayle approaches his work in two major ways: first, to gather facts and analyze them; secondly, to interpret the facts and analysis in a report, adding judgments and recommendations which will assist in determining strategies.

Quayle has a small, central staff which varies from four to about fifteen men and women who help him run the main office. His computer work is all done independently by an outside firm. The Quayle organization also has a number of field supervisors, covering states or areas, who recruit and train the public opinion polltakers, a group of part-time workers numbering about 2,000.

"I think there are five main keys to this business of public opinion surveying," Quayle says.

"First, good interviewing which means getting a correct sampling, and here you must have a good statistician.

"Secondly, you must prepare good questions.

"Third, the interviews must be comprehensive and probe in depth. Some of our interviews may last an hour.

"Fourth, the results must be carefully cross-checked and cross-referenced so both strengths and weaknesses may be analyzed by area, groups, etc.

"Fifth, and most important of all, there must be the ability to interpret all the findings thoroughly and correctly and to reflect judgments from this interpretation in a final report. Here is where all your past experience, your knowledge and skill come into practice."

We had been talking with Quayle on a Sunday afternoon at the home of Ad Winship '42, a classmate and former roommate. The dinner hour was approaching but before taking our leave we asked Quayle a final question about the impact television coverage of primaries and elections might have on voting, particularly the TV projections which are flashed from the East before voting booths are closed on the West Coast.

"I think this has been highly exaggerated," he answered. "The University of Michigan has already done some studies on this subject, and they do not show any significant last-minute change in votes because of television reporting. Additional studies are now being carried out, and I predict these studies will show a very minimal effect by TV on voting habits. I don't think any great number of people can be influenced in their voting by any trends that might be reported on TV networks, particularly on election day."

Oliver A. Quayle III '42, in Hanover last monthwhen he, John Steele '39 and Thomas Schroth '43were on a post-election panel for Great Issues.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureVANISHING ABSOLUTES

December 1964 -

Feature

FeatureOur Battle To Reform The Education of Teachers

December 1964 By THOMAS W. BRADEN '40 -

Feature

FeatureTwin Pillar of Alumni Support

December 1964 By FORD H. WHELDEN '25 -

Feature

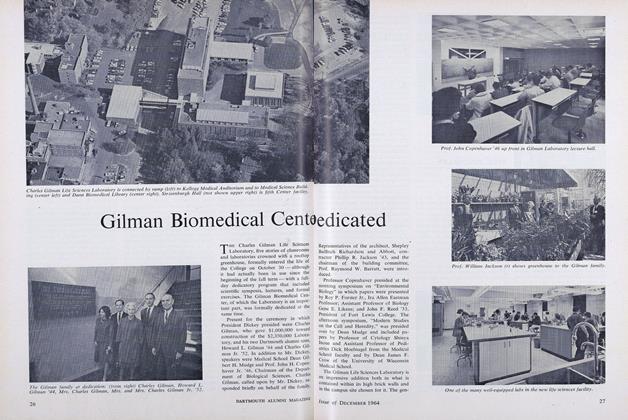

FeatureGilman Biomedical Centedicated

December 1964 -

Article

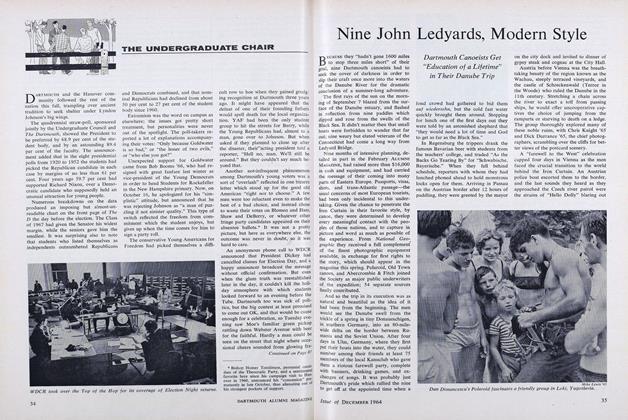

ArticleNine John Ledyards, Modern Style

December 1964 By BOB WILDAU '65 -

Article

ArticleWITH THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

December 1964

CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45

-

Feature

FeatureCarnival Post-Mortem

March 1956 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Article

ArticleThe Russian Review's 20 years

February 1962 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

FeatureDr. Seuss

OCTOBER 1962 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

FeatureThe Cold, Cold World of CRREL

FEBRUARY 1964 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

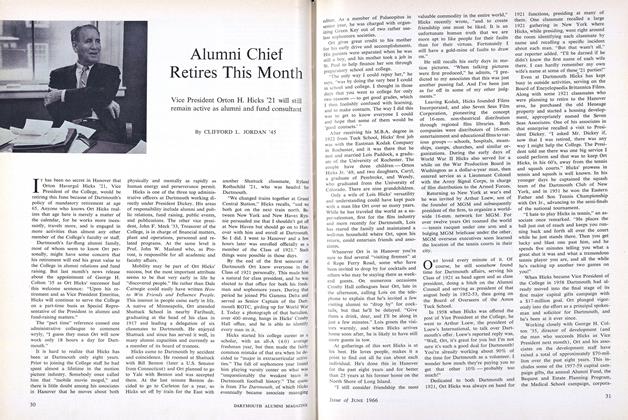

FeatureAlumni Chief Retires This Month

JUNE 1966 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

FeatureAN ATHLETIC SUMMING UP

JUNE 1967 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45

Features

-

Feature

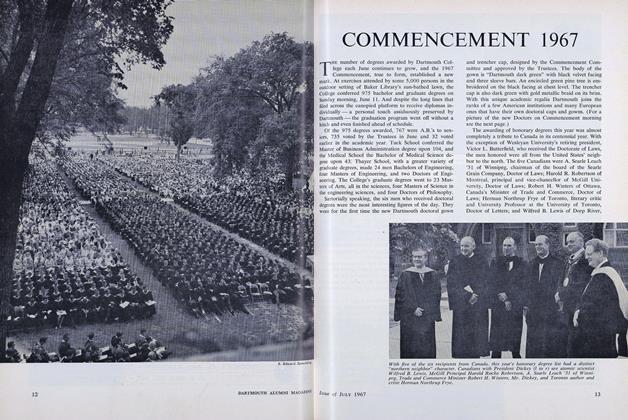

FeatureCOMMENCEMENT 1967

JULY 1967 -

Feature

FeatureAmerican Musicologist

MAY 1972 -

Cover Story

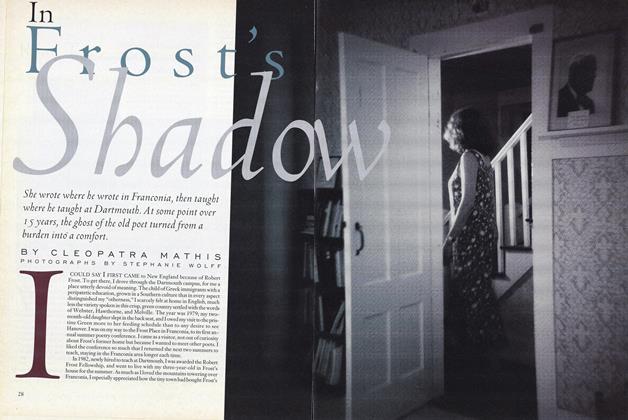

Cover StoryIn Frost's Shadow

SEPTEMBER 1997 By CLEOPATRA MATHIS -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO HOOK VIEWERS WITH AN ADDICTIVE SOAP OPERA STORYLINE

Jan/Feb 2009 By JEAN PASSANANTE '75 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

Jan/Feb 2008 By JOSEPH MEHLING '69 -

Feature

FeatureAlzheimer's Disease

MAY 1985 By Peter Blum '85