SPECIAL ASSISTANT TO THE PRESIDENT

THE word on the campus is that business is for the birds."

So started a lead article in a recent issue of the Wall Street Journal (Nov. 10, 1964). Other periodicals recently have carried stories reporting undergraduate disenchantment with business and citing facts and figures in support of this contention.

As might be expected, several Dartmouth alumni have expressed their concern with this situation and have asked us for the facts as we find them. They need not have asked, for we were equally concerned, and were already taking a closer look at the situation as it exists on this campus.

We draw but one conclusion. The reports are based in good part upon half-truths and in total they represent a distortion of the facts.

First let us take a look at the charges. The Journal article continues:

"At college after college an increasing percentage of graduates is shunning business careers in favor of such fields as teaching, scientific research, law and public service. Amherst College says 48% of its alumni are businessmen, but fewer than 20% of recent graduates have been entering business. Only 14% of last spring's Harvard graduates plan business careers, down from 39% five years ago. ... A June graduate of Stanford University says of his classmates: 'I know of almost no one who even considered a business career.' "

The story continues by citing impressions and reports from various campuses which seem to strengthen the case that today's graduating seniors take a dim view of the business world. They regard it as a high-pressure conformist place where superficial values prevail. The businessman is the man in the gray flannel suit with the martini ulcer who is apt to be judged more by the design of his tie and whose first responsibility is not his fellow man but his company's profits. He is preoccupied with thoughts of sales promotions and planned obsolescence, and his world is an intellectual Siberia.

The story goes on to say that faculties mock the businessman and in general contribute to the low esteem in which he is held by young men about to embark on their careers.

In fairness to the Journal article, it probes the validity of these points and takes fair recognition of the many factors in our changing society which are bound to cause shifts—real or apparent—in the career choices of the nation's best-educated young men. The demand of business for qualified candidates is rising at a faster rate than the increase in the number of graduates. Competition from other fields is growing sharply, especially in the areas of public and social service, the professions, and from education itself. Improved earnings potential in these fields has made them more attractive, or certainly less unattractive than previously. Graduate schools especially are competing with corporate recruiters for the growing number of young men who feel that an A.B. degree is no longer an end-point to formal education.

But the point we wish to make is that the Journal story leaves the reader with the distinct impression that this is a frightening situation, that business is indeed for the birds. And especially so among the graduates of the leading private institutions, and the Ivy League in particular.

We feel this simply is not so, and although we can speak only from the evidence found on this campus, we believe the reports are an exaggeration of the situation on other campuses as well.

Essentially, there exists a good deal of confusion over the difference between immediate post-graduation plans and ultimate career pursuits. Many colleges canvass their graduating classes for information on immediate plans, but few probe the long-range objectives. The Harvard report, for example, admits that its next project is to survey a class a few years after graduation to learn what actually happens to its men.

AT Dartmouth, the Office of Student Counseling has concerned itself with a study of the future plans of the College's graduates. Its report entitled "The Class of 1963: Its Vocational and Educational Plans" is the latest published study of career goals as of both matriculation date and graduation date. It contains interesting evidence in support of our thesis, especially if one studies the long-range rather than immediate plans.

Of 640 men who graduated, 200 indicated ultimate career plans in the business field (accounting, advertising, banking and finance, industrial administration, insurance, etc). Another 227 were headed for careers in fields which could well lead into or be construed as business (architecture, aviation, forestry, journalism, corporation law, and scientific research, plus the 70 men who reported themselves as uncertain). The remainder, 213 in number, planned non-business careers (drama, foreign service, government, medicine, military career, music, religion, social work, teaching, etc.).

Thus 31% were headed for business careers, 33% for non-business careers, and the remainder in time will fall either way. It is a fair guess that the ultimate balance will be about fifty-fifty.

This is quite a different picture from that gained by studying the section entitled "Plans of the Graduating Seniors," a study of their immediate plans. Only 66 men planned to enter business right away. (The remainder of the Class: 385 to graduate schools, 99 to military service, 24 to Peace Corps and other foreign travel or teaching programs, and 64 uncertain.) From the corporate recruiter's standpoint, this does not present a very bright picture. But the statistics do not necessarily reflect ultimate career objectives. They should be interpreted as a challenging trend of the times rather than as evidence that graduates are shunning business.

Even though only 66 men go into business right away, approximately 150 men sign up for placement interviews in the spring of senior year. Donald W. Cameron '35, Director of Placement, states that interest in placement interviews is fairly steady in spite of the high number with plans other than immediate employment. This is further evidence that many men who plan graduate study are considering eventual business careers. Mr. Cameron also reports a steady traffic in inquiries from young alumni after completion of their military service or other temporary commitments. Perhaps business should be encouraged by the fact that young candidates elect to strengthen their qualifications for business careers through further graduate study.

To the charge that the faculty brings anti-business persuasion to bear on students, the Dartmouth study suggests this simply is not so. On matriculation, 224 men of the eventual graduates of the Class of 1963 planned a business career. Four years later the number, as noted above, was down only slightly to 200. Similarly, the number who aspired to non-business careers shrank from an identical 224 at matriculation to 213 at graduation. The only firm conclusion one can draw is that the "uncertain" category grew - from 10 to 70.

Dean Karl Hill '38 of the Amos Tuck School of Business Administration is inclined to discount the charges that academicians are unduly cool to business. "On any campus, or in many another segment of society for that matter," he says, "there is bound to be a range of divergent opinion about business as a career. But today a larger segment of the academic community enjoys a much closer relationship to the business world than it ever has before. There is a growing intellectual relationship between the two which is bound to strengthen their mutual respect."

The figures we have presented are not intended as conclusive proof of anything. But they do provide healthy evidence that there is a strong interest on the campus in eventual business careers. We doubt that many students here can say they know hardly anyone even considering a business career.

It is unquestionably true that many students have a deeper sense of purpose than students of a generation ago. This is as it should be. Totally new opportunities for service exist. Greater issues call urgently for participation and leadership. At the same time, there is less urgency to find a job for "subsistence sake."

Perhaps it can be argued that underlying the confusion and uncertainty which perpetually plagues young men weighing career choices there is a far deeper sophistication than heretofore. Dartmouth men generally have a pretty fair idea of what they want to do. Considering their wide range of choice, it is not unreasonable to state that a decision for a business career is just as thoughtfully reached as is a decision for teaching, or foreign service, or scientific research.

The purpose of the College is to educate potential leaders for a wide range of service to our society, and we think that Dartmouth is accomplishing this in good balance.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA NEW BREED OF CHUBBER

February 1965 By JOHN ALDEN THAYER JR. '65 -

Feature

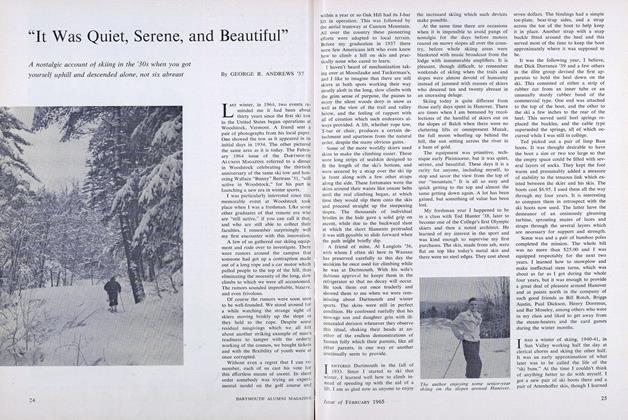

Feature"It Was Quiet, Serene, and Beautiful"

February 1965 By GEORGE R. ANDREWS '37 -

Feature

FeatureFreshman-Sophomore Curriculum Revised

February 1965 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

February 1965 By BOB WILDAU '65 -

Article

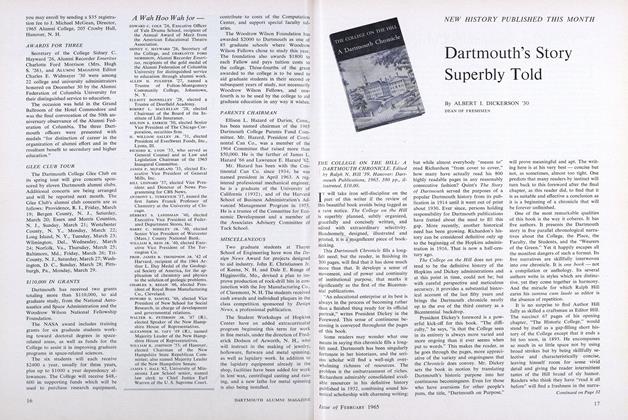

ArticleDartmouth's Story Superbly Told

February 1965 By ALBERT I. DICKERSON '30 -

Article

ArticleThe Battle of the Non-Teachers

February 1965 By M. DANIEL SMITH '46

Features

-

Feature

FeatureA Message from the new Fund Chairman

NOVEMBER 1962 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryRick Adams

OCTOBER 1997 -

COVER STORY

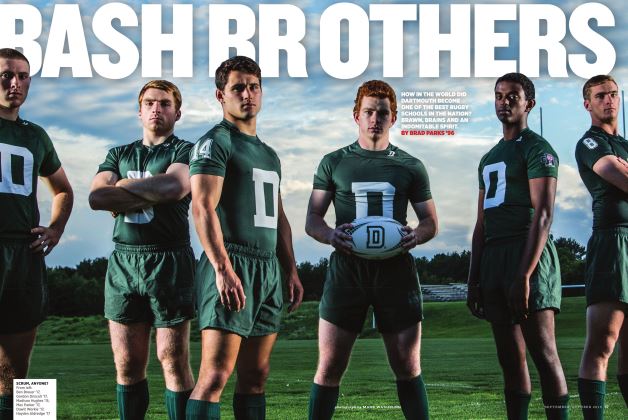

COVER STORYBash Brothers

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2015 By BRAD PARKS ’96 -

Feature

FeatureThe Assault On Quebec

December 1975 By LEWIS STILWELL -

Feature

FeatureDweck & Ivey's Good Offense

JANUARY 1998 By LINDA TITLAR -

Feature

FeatureSenior Valedictory

JULY 1972 By ROSS P. KINDERMANN '72