An archival search concerning the Fang peoples of Africa is pursuedon three continents and ends successfully in, of all places, the lowerreaches of the Dartmouth Library.

ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF ANTHROPOLOGY

I AM not a Dartmouth man and can only guess at what it is to be one. But I have known the work of some which has impressed me. I was recently, for reasons I will set forth, overcome by the Rev. Benjamin Griswold, Class of 1837. Since the first week of March 1965 he has become a historical figure of first rank to me. It may be that he has high place only in my personal pantheon. But all of us, even those of us from the younger institutions in western Massachusetts, participate in one alumni cult or another, yearly reconsecrated, tabulated with the most careful necrology, nurtured by ritual specialists. We are all enshrined somewhere in some institution of higher learning, if not on the Hanover Plain, then in the bleak Berkshires or in the fertile pioneer valley of the Connecticut. We all sacrifice to foster a brighter flame, to build a better citadel for our lineage in the company of those things we value the most: intellect, vigor, fellowship, commitment. Benjamin Griswold, Class of 1837, is one of Dartmouth's ancestors. I mean to recount something of his story.

From the summer of 1958 through the summer of 1960 I, with my wife, conducted anthropological field research among the Fang peoples of northern Gabon and Spanish Guinea. Though the Fang have since pushed their conquest of Equatorial Africa through to the coast and the fleshpots of European commerce established there, they were in the last century a pristine people of the dark interior steadily pushing across the plateau, poised upon the coastal escarpment, imminently to descend upon the autochthonous tribes of the coast. Their advance was glacial and the terror they provoked was legendary. Tales of their warlike ways, their cold vengeance, their cannibalism, were widespread and though little was known about them firsthand, the reports of their presence and the occasional account of an explorer or trader were celebrated in the nineteenth century European journals of popular exploration - Globus, Tour du Monde, and the Illustrated Geographic. They rapidly became one of the type cases of African savagery and civilization.

I say savagery and civilization because the image of the noble savage was still prevalent among nineteenth-century Europeans and conditioned their perception of the primitive. The explorers who, fascinated by the terrible Fang, struggled in to meet them almost always came away with a complementary view of their high moral sentiments — straightforwardness and simplicity and sincerity, coupled with the devilish instruments of atheism, cannibalism, and witchcraft. The elemental ambiguity of the heart of darkness as a symbol was accompanied by such ambivalent reactions to its inhabitants.

are bound by subtle links. And we have the more admiration for our predecessors, for they were abroad in a wilder day, when the imponderables of exploration were much greater . . . when the nobility of the savage had to be taken on faith while his savagery was self-evident. It can be easily understood, I think, how interested any anthropologist is in those who may previously have explored the people he has studied. This is not only for the scientific value these accounts may have but for frankly sentimental reasons. One is undergoing considerable hardships to carry out what must be, in the general view, recondite research. Who previously was driven to such extremes in the pursuit of a knowledge without wide regard? We

No man, moreover, however scientific his interests and objective his stance, can wholly escape stereotypes in his approach to another culture. It is always of interest in our struggle to escape bias to consider the pedigree of the perspective that comes most easily to us. This is particularly the case in Africa.

At the time of my research I was aware that American missionaries had made early contacts in Gabon. I knew, for example, that Albert Schweitzer was not the first doctor on the Ogoowe River at Lambarene. In fact, some forty years before Schweitzer, in the 1870's, Dr. Hugh Hamill Nassau, a Princetonian and Presbyterian, was missionizing over a day's journey above Lambarene up the Ogoowe into the interior. But since Gabon at the period of our study was so thoroughly the province of French cultural chauvinism I had supposed that the early contacts were all French as well. Certainly the history taught in the colonial ecoles and lycée emphasized French exploration and settlement almost exclusively. I knew that American missionaries were very early on the coast. But they had been expelled from the colony in the early 1890's because they preferred teaching in the vernacular and because their knowledge of French failed of that Cartesian precision of expression to which the French aspire and take a just pride. Not only had they failed to learn sufficient French, I must have supposed, but they had really failed to make any significant impact.

As I followed up field work with the exploration of European and American archives, however, the misrepresentation of nineteenth-century colonial history fostered by the French became clear and I discovered a more rewarding antecedence. Paul Du Chaillu, now a forgotten cause celebre, was an African-born Frenchman who turned American and Protestant and hunted gorillas, cannibals, and pygmies in Africa in the early 1860's. He reported all this flamboyantly for the English and American press. It is true that his reports on the West Coast gorilla were the first eyewitness accounts we have of that beast, but his reports of cannibalism and pygmies were so overdrawn as to provoke the skepticism, even, of an age avid for outlandish adventure in Africa.

Du Chaillu visited the Fang in 1857. This brief penetration of "cannibal country" was, for all I could tell from the European archives, the first substantial sojourn among our friends, and it was from Du Chaillu's visit that I dated the beginning of Fang westernization. Du Chaillu's accounts were of some scientific interest, though flagrantly deceitful in respect to cannibalism and physical appearance, matters which he felt called upon to report in as provocative a manner as possible.

So matters stood between myself and my predecessors on the western Equatorial plateau. Upon my return to this country in 1961 a delay in trans shipment of our baggage through New York enabled me to combine a visit with friends in Philadelphia with a visit to the Presbyterian mission archives in that same city. Here, with a sense of real discovery, I turned up letters and a report confirming an exploration and sojourn among the Fang in the Crystal Mountains by one Rev. James Mackey as early as 1853. This exploration undertaken in the name of opening up the interior to evangelization sounded strangely, in details of travel, like that repeated four years later by Du Chaillu, who, since he departed as well from Cerisco Island for the Muni estuary, must have been obliged to the missionaries stationed there for hospitality and information. But Du Chaillu mentions the missionaries not at all in the account of his "original and true" contact with the terrible inhabitants of cannibal country. I must say that it was with some sense of patriotic and professional satisfaction that I retrieved the Rev. Mr. Mackey's gospel light of exploration from under the dusty bushel of archival oblivion.

My satisfactions were short-lived, however. M. le Gouverneur Deschamps, the eminent French Africanist who has been recently interested in Du Chaillu and the history of Gabon, responded to my letter on Du Chaillu's debt to Mackey by pointing out early visits to Fang villages by several French naval lieutenants, commanders of frigates, who were probing the headwaters of the Gabon estuary for illicit slavers and in the interest of establishing France's recent claim to that part of Africa. These villages were Fang descended from the pristine centers of the Crystal Mountains in search of commerce and European goods. But the reports of these French lieutenants, dating from 1846, proved sufficiently detailed to qualify them at that point in my historical scholarship as the "original and true" predecessors.

M. Deschamps was kind enough to make mention in a postscript to his letter of the possibility of further information in The Missionary Herald, the nineteenth century quarterly of American mission activity. But The Missionary Herald proved a rare journal in the several libraries to which I subsequently had ac- cess, and since my professional concerns were primarily with the contemporary Fang the banner of discovery remained for several years with the French lieutenants.

On Friday, the first week of March 1965, I had the occasion while checking bibliography in the card catalogue at Baker Library to see whether The Missionary Herald might be in the Baker collections, whose richness in a number of unsuspected areas I had previously discovered. In fact, as it happens, the Library possesses the entire set. The importance of this fact caused me to drop all other work and descend immediately to the lowest level of the stacks at the farthest end of the corridor in an aisle placed so near to the outer wall as to force the browser to sidle in with no possibility of squatting for closer examination. There on the bottom shelves I dimly made out the leather-backed volumes of The Missionary Herald. By further squeezing I was able to remove the volume for the year 1846, the year the French lieutenants first came upon the Fang.

Retreating to a nearby carrel, I opened to the index. The leather was old - of that kind so parched that it comes off in a light brown powder on the user's hands. Could these volumes have been consulted as much as twice in the last hundred years? There in the index, my sense of piqued interest will be understood, were found frequent references to the Fang - for all the world as if they were old friends of the American mission- aries. I returned for an armload of earlier volumes and worked backwards; 1846, 1845, 1844, 1843, still the Fang were mentioned. In 1842 appeared an account of the establishment upon the Gabon Estuary, in the name of the American Board of Foreign Missions, of an outpost of Equatorial evangelization by the Rev. Messrs. Wilson and Griswold, the man who accomplished it. Even in that earliest account, while the two missionaries concentrated upon the coastal peoples among whom they were established, they made mention of the great possibilities of the interior, where a vast hinterland of pristine peoples untouched by the degenerated influences of coastal commerce awaited conversion.

The attraction of the interior and the noble savagery of its denizens, particularly the Fang, is so fulsomely expressed in these first accounts of the Gabon mission that some attempt to make contact with them is clearly foretold.

This is particularly the case in the accounts of the Rev. Mr. Griswold. Thus in the volume of 1844 we are rewarded to find mention of an extended trip back into the interior among the Fang made by him. This trip, then, could not fail to be the first contact ever made with the Fang, since the French presence at that period was not effectively established on the estuary. With anticipation I hurried, therefore, to the 1845 volume, where this exploration was to be reported. But I searched in vain. For here was noted with sad respect the passing of the Rev. Benjamin Griswold "'taken by a fever several weeks after his return from the exertions of a trip into the interior to make contact with the Fang." The Rev. Mr. Wilson notes ruefully that the trip journal kept by the explorer was as yet in such an unfinished state as to be "of very little use to us and none to the outside world."

In a later number, as was the custom in The Missionary Herald, which had many missionary deaths to report in the nineteenth century from the West Coast of Africa, there was a brief obituary of Benjamin Griswold. He was born in Randolph, Vermont, and, I read on, educated at Dartmouth College, Class of 1837. That stopped me short! Here was I, sitting in the nether regions of Baker Library, motivated by a very idiosyncratic interest - there is no other person in America and perhaps in the world who could have that same interest - suddenly discovering that the person to satisfy that interest and to first make contact with the Fang was a graduate of Dartmouth College. That concatenation of circum stances that passes for the world and history suddenly coalesced for me into something like a meaningful configuration. I felt momentarily to be part of an inscrutable intention and teleology, almost as if I had been returned to the Fang to pick up where Griswold had left off and then brought subsequently to Dartmouth to fittingly complete a chapter which fever had abbreviated in 1844. But that feeling passed quickly. It is something the Fang, or perhaps even Benjamin Griswold, could believe in. Skepticism had made too many inroads on religion and analysis on philosophy to give such a sentiment the support of intellect in twentieth century Dartmouth College.

Subsequently I made inquiries about Benjamin Griswold in the Baker Archives with the hope that his exploration papers might be preserved there and that I might rescue them for science. The archives possessed, however, only the journal of his trip out to and his first months in Liberia sent home to his family before he departed for the Equator. The grace, perception, and surprising tolerance with which he examined African custom in that journal made it clear that we were missing much in not having even his notes taken among the Fang. Hopefully they still exist in some Vermont attic or in some mission archives and will one day turn up.

MY archival odyssey in search of my predecessors among the Fang has come to its farthest historical point, I believe, in the discovery of the Rev. Benjamin Griswold. As we move forward in time, historical scholarship makes progress into the past and one cannot guarantee to the Rev Benjamin Griswold the distinction he now holds. But all we know would suggest he rests secure: the first white man among the Fang. It is surprising and gratifying that this first explorer should be an American. It is astounding in my present circumstances that he should be from Dartmouth.

Men of the College to whom I have accounted this series of events have been matter-of-fact in its reception. After all, there is the Ledyard legend, which also ended in Africa, and a tradition of robust adventuresomeness that easily encompasses the Rev. Mr. Griswold. But I say, homage to him! I know what it is to go out and live upcountry on the Equator. I understand his attraction for the Fang. I came down with fever myself. And but for twentieth century prophylaxis I might have left but a few scattered notes in the archives of a New England college.

I perceive dimly, if I may conclude in this way, that there is something more in this account than a set of curious historical circumstances. At this period in American history, where our power in world affairs is so manifest and where we are frequently confronted with challenges to our self-restraint - our strain towards omnipotence - in the exercise of this power, it is salutary to reflect upon the Rev. Benjamin Griswold. He was, like so many of his colleagues, so motivated by an ideal and an idea that he was ready to thrust himself into a situation in which he was virtually powerless. He had a message and to communicate it he was ready to confront other men directly, however exotic their culture, without the panoply of power to support him. I would say there is more in this than a blind religious zeal; there is also a fundamental humanitarian confidence, and even a certain realism about human affairs. While there may be greater dangers abroad in our present world than tribes of noble savages, so that our power is an inescapable preservative for us, nevertheless if we should consult such of our nineteenth century ancestors as the Rev. Mr. Griswold I should imagine he would say in the strange and paradoxical phraseology of the Bible: without an ideal and an idea to which they are ready to bear witness under any circumstances, the most powerful men are in any lasting sense powerless. The mighty, he would probably say, who cannot express them selves meaningfully to their fellow men will soon be brought low. Of course, he may secretly have felt himself the vanguard of a surging manifest destiny.

Ah, well, the problem with consulting ancestors is that their words are always too mystical to have any real relevance to our present and very practical problems. What Griswold seems to be saying, like another sage of that century, is that power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely. But that's an impossible notion to accept in an affluent age in a Great Society, where the sovereign axiom is - play it cool and carry a big stick!

The Author: Professor Fernandez, shown in the Dartmouth College Museum, taughtat Smith College before coming to Dartmouth in 1964. He is an Amherst graduateand holds a Ph.D. from Northwestern. He has traveled in Europe, Africa, andRussia, and has served as a Peace Corps area consultant and as lecturer for theForeign Service Institute in Washington. He is now in Durban, South Africa.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

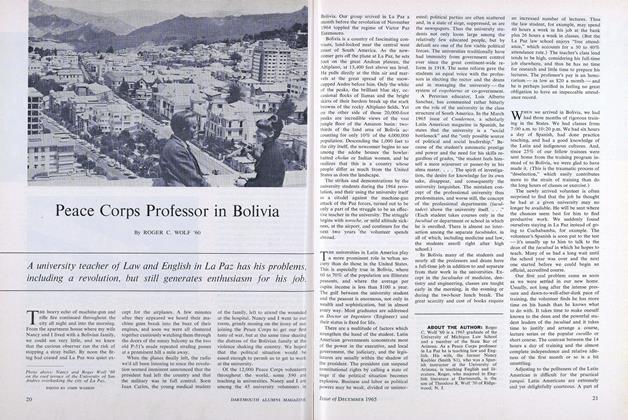

FeaturePeace Corps Professor in Bolivia

December 1965 By ROGER C. WOLF '60 -

Feature

FeatureA Major Geological Discovery

December 1965 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

FeatureA Football Victory Hanover Will Never Forget

December 1965 By R.B. -

Article

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

December 1965 By ERNIE ROBERTS -

Article

ArticleThis Mother of Seven Dartmouth Sons Read Every Book in the College Library

December 1965 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Article

ArticleThe Campus Examines Public Issues

December 1965 By LARRY K. SMITH

JAMES W. FERNANDEZ

Features

-

Feature

FeatureAlumni Council Dinner Honors Football Team

FEBRUARY 1959 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryMurray Hitzman '76

March 1993 -

Feature

FeatureThe Marxist View of Overpopulation

JUNE 1971 By Charles W. Collier '71 -

Cover Story

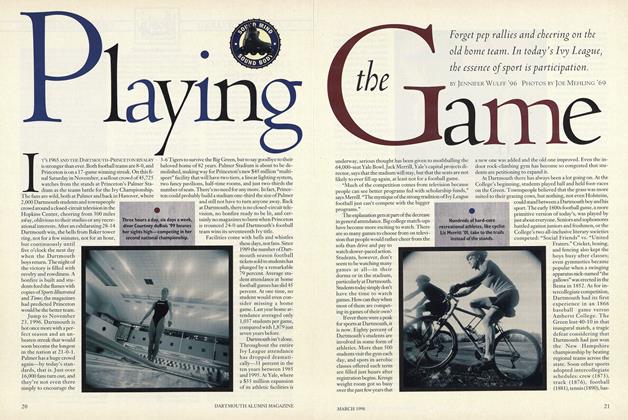

Cover StoryPlaying the Game

March 1998 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

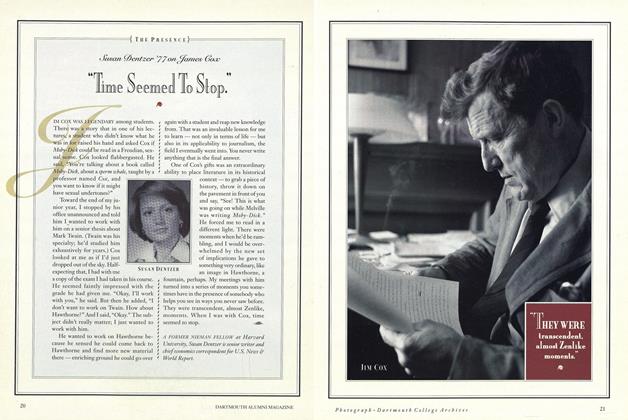

FeatureSusan Dentzer '77 on James Cox

NOVEMBER 1991 By Jim Cox -

Feature

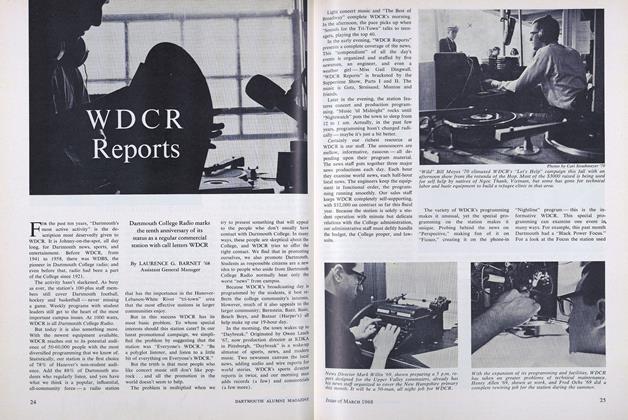

FeatureWDCR Reports

MARCH 1968 By LAURENCE G. BARNET '68