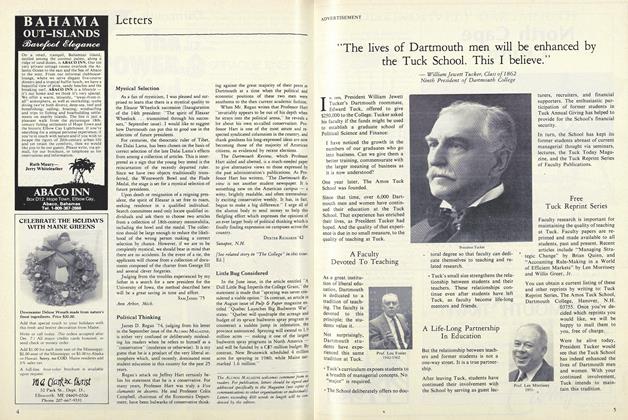

A Near Disaster for Four Dartmouth Climbers

CERTAINLY three, and probably seven, mountaineers died on Mt. McKinley this summer. The appeal and the hazards of this 20,300-foot mountain would appear to need explanation. My experiences on a "successful" climb via the South Buttress of McKinley, which coincided with the disastrous climb on the North, should illustrate both aspects of this kind of expedition climbing.

Our expedition of fifteen men had a threefold purpose: 1) to climb a new route on the South Face, 2) to train men for an eventual attempt on a Himalayan peak in two years, 3) to furnish the University of Alaska with physiologic data before and after a strenuous high altitude climb.

Our expedition was six months in preparation. The climbers, drawn from all over the United States, included seven Dartmouth men: Dennis Eberl '65, Graham Thompson '6sa, Paul Kruger '68, David Seidman '6B, Michel Zalewski '68, James Janney '69, and myself. Most of the preparatory work fell on the leader, Boyd Everett, an investment banker with a consuming interest in expedition climbing and extensive experiente in Alaska.

As the expedition doctor, my comparatively modest task was the preparation of three medical kits for the three routes. It was a lesson in practicality to pare down the modern medical armamentarium to essentials only. The American Alpine Club generously sent a mimeographed sheet of recommendations by a committee of mountaineering doctors. The drug companies, particularly Rexall, were prompt in their donations of antibiotics, skin salves, and nostrums. We carried a half hour of oxygen for pulmonary edema in aluminum bottles kindly donated by the manufacturer, LifO-Gen. (After the summit, in our camp at 18,000 feet we sucked from these bottles in lieu of cocktails.) The most valuable items in our kit proved to be aspirin, which was effective against highaltitude headache, and Seconal, a short acting barbituate effective in the induction of sleep under the peculiar daytime conditions of the glacier. Climbers who had slept well could be spotted by their cheerfulness.

Because of hospital duties, I missed the buying and packing of food at Fairbanks. One thinker calculated that it would take one man between four and six months to do the job thirteen men did in three days. Breakfast was oatmeal or cream of wheat followed by cocoa. Strange to say, cold cereal proved an exceedingly popular change of pace. I suppose its crispness accounts for this. After weeks of mush, one developed a ravenous appetite for crackers and cookies. Lunch was nuts, three candy bars, half a can of kippers, sardines or tuna, and flavored water, usually Wyler's. Supper consisted of a dried soup followed by canned meat and rice or potato. We always drank jello or pudding hot, a beverage New Englanders might try on a bitter January day. In short, ours was standard expedition fare; we could not buy the more sophisticated dried foods because purchasing was done in Fairbanks, not exactly a world-trade center.

The expedition was in full swing when the glacier pilot, Don Sheldon, flew me to base camp a week late. The shock of being lifted from a virtual rain forest to 7,000 feet on McKinley was great. Nothing grows there. No living thing. Immense masses of snow and ice are heaped on all but the steepest pitches. There are no sounds except the wind on the tents and the intermittent thunder of avalanches falling somewhere. I was dressed for ice fishing in Antarctica. These clothes were quickly discarded in the twenty-degree, windless weather. I was soon surrounded by men who had lived in that forbidding landscape for a week, a fact which in itself I found reassuring.

There followed two weeks of carrying loads from base camp at 7,000 feet to advanced base camp at 10,000 feet. Many have asked whether I, as a resident in Surgery, could find time for conditioning before the trip. I could, but my efforts were insignificant compared to these two weeks of ferrying on the glacier. Every night we carried 50 lbs. five miles and 1,500 vertical feet on snowshoes. This labor cannot be duplicated in ordinary life. Perhaps the only time men push themselves this hard is in combat.

Gradually one acclimatized to Sherpa life. Trudging along in the semi-darkness, one's thoughts focused inwardly. Revery was possible when a rhythm was established. On the return to base camp, one could frequently walk on the crust without burdensome snowshoes. The dawns were crystalline and the peaks topped with molten gold. Conversation over breakfast was lively because of the diversity of our backgrounds. A doctor of philosophy in religion, a student of forestry, and a medical doctor would earnestly discuss the nature of woman over cocoa, before an immense fatigue forced them to their tents. Life was simple.

By July 12th the three routes, including the new one, had their first camps established. My party, whose purpose was to fix an escape route for the other two, was reduced to a minimum of four when a rock-climber took a careful look at expedition life, decided it was not for him, and ran off the mountain unescorted in record time to base camp. I was left to climb with three Dartmouth undergraduates Jim Janney, Paul Kruger, and Michel Zalewski.

Our first camp was at 12,000 feet. The route to it, the only way we could find, was a bit too close to a hanging glacier, but we had no choice. This part of the route caused trouble later. The weather held sunny and within three days we had established a camp at 15,000 feet.

We first became conscious of the altitude at 15,000 as headaches and breathlessness occurred. We had time to acclimatize, however. We could tell the weather was changing by a curious cloud cap, like a beret, on a nearby peak. This almost invariably means snow in two hours. We spent five of the next six days in the tents.

Many have asked what one does to pass the time for five days in a tent. The problem is by no means acute. After three weeks of Sherpa life, and because of altitude, one's mentality is blunted. Time passes quickly, if you are able to sleep 14 hours a day. Cooking breakfast and supper took 2-3 hours because of the fickle nature of the stove and the necessity of melting snow. Reading and journal writing consumed the remaining hours. For expeditions I favor French novels because they yield more reading time per pound, if you read French as slowly as I do. The Dartmouth students all read The Rise and Fall of the ThirdReich simultaneously by chopping it in thirds.

On July 23rd we were able to move our camp to 16,000 feet, a windy col reached by a long traverse. The weather turned foul as we were leaving. It was my misfortune to carry the tent this time. When the wind stiffened, it threw the tent over my head, thus beating me to the ground repeatedly. We could not turn back because the other half of the party would be left without a tent. Visibility dropped to ten feet. After five hours we reached the broad, flat, contourless, fogbound col where we promptly lost our way in the white-out. We wandered in a complete circle finally intercepting our own tracks. At that moment, the white- out lifted allowing us to see the green willow wands used to mark the trail. We found our companions at our campsite behind an immense snow wall they had constructed while waiting for us and the tent.

On July 24th, when we were confined to this campsite by the now familiar southerly wind, snow, and fog, we first heard of the disaster on the North side of the mountain. We were surprised by the news because the weather was to be expected at this time of year. We could not help; we were several miles from the scene. We waited, poised for the summit, for a definite change in the weather. The change came on the 27th, which was the first of three sunny, windless days in succession. We moved camp to 17,600 and the following day started for the summit.

The altitude made the 12-hour climb, not technically difficult, arduous indeed. I was continually nauseated and wracked by headache. We moved as slow as invalids, four breaths to a step. We reached the summit at six in the evening after a half-mile traverse on 35-degree ice. The temperature was eight below zero without a breath of wind. Having reached the summit, our greatest desire was to leave it, and after taking a few photographs, we began a pleasant descent. For the first time, I could enjoy the climb. But this enjoyment could be interrupted by the slightest upward deflection in the track; nausea and headache would return if I had to step up even a few inches. We made camp in three hours.

The four of us were jubilant. To have climbed McKinley is something - just what it is, in view of subsequent events, I am not sure.

The following day was our third with sun and without wind. Clouds from the north in sleek squadrons held fluffy, pacific storm clouds at bay. We had a substantial midday meal before descending, but mistakenly did not melt water for our canteens in the interests of a quick start.

The afternoon was unforgettably beautiful. The sun gilded incredible cloud formations far below us. We stopped to photograph snow cornices etched by indigo shadows. I was on the second rope of two. We were about to negotiate the second icefall near the hanging glacier mentioned at the start of the actual climb, when we heard a sound like a rifle shot. A mile above us and to the left of the track we had just descended, an enormous avalanche had started.

For a moment, it seemed a distant event, scarcely disturbing the evening calm, but we were in its path. I looked around, but there was no shelter. A huge, boiling snow cloud thundered. towards us. At the second I could at last perceive that we would certainly be hit, we were in fact hit by titanic wind and snow. I was rolled over and over for two hundred feet, like a child at the beach caught in a great comber. I thought I was dying. Then the turmoil ceased I was weightless, suspended in air.

The wind whistling past me told me I was falling. This is death itself, I thought. An image of a painting depicting one of the first deaths on the Matterhorn flashed into my mind. There was plenty of time to think because I fell 130 feet, or thirteen stories, into a cavernous crevasse. Then imperceptibly, slowly, I stopped falling, I knew not why. Cascading snow formed an opaque curtain around me as I hung upside down unable to interpret what had happened. When, after many minutes, the avalanche ceased, I could see that I was hanging by the climbing rope which must be attached to my climbing partner, Paul Kruger, whom I thought buried beneath tons of snow.

At first, efforts to extricate myself seemed futile, since I was surely marked for death. Gradually, I came to preceive that my situation was not hopeless. I was only twenty feet above the bottom of the crevasse, which had been filled in with ice and snow. Moreover, the crevasse seemed to open out into the glacier at one end. This flicker of hope increased my anguish because I was rapidly losing strength. The waist loop constricted breathing so much that unconsciousness seamed near. The pack turned me upside down.

My first efforts were pointless. I tried to fix myself to the wall of the crevasse, a maneuver of no value at all. After many minutes, I remembered the proper sequence of actions. Drop the pack so that it hangs from the end of the climbing rope, I told myself. This allowed me to work rightside up. I took off my one remaining snowshoe and so was able to step up into the stirrups we always fix to the rope for this eventuality. Now I was relieved of the terrible constriction of the waistloop. About this point in my efforts at self-help, Paul called my name. Never a sound more welcome, relief more profound. Paul had a wonderful stoic calm on the trail. He was lucid now.

"What do you want me to do?" he asked.

"Lower me," I replied

Magically it seemed, I was lowered from the gallows. We discussed my plight. The usual method of climbing out of crevasses seemed impossible because the rope had cut into an immense cornice. Moreover, it appeared an easy scramble out onto the glacier. I elected to unrope and climb out of the ice-fall alone. In retrospect, I think I should have tried to climb the rope, but the memory of the cornice has faded and that of the icefall is all too vivid.

After picking my way for an hour in the deep snow and ice blocks, sensing that each step would drop me into a dark tomb of ice, there to die slowly over the course of days, I could see that the crevasse did lead to the glacier, but that a 150-foot cliff of ice was interposed. Panic was close to the surface now. I saw another opening in the gathering darkness. Without crampons, I slipped and fell continually on my way towards it. The opening proved fruitful. A snow cone from the smooth surface of the main glacier pointed towards me, with a short ice cliff intervening. In the darkness (it was now midnight) I could not be certain whether it was fifteen or fifty feet high; it looked like fifteen. I knew I would fall on the pitch and did, but I merely spilled out on the glacier in a gentle snow slide. Only at this moment did life seem certain. Paul and I met a half-hour later.

He said our route down the icefall was unrecognizable. Seracs had toppled. The normal six-foot cover of snow had been swept off leaving polished ice where we had been snowshoeing. He had been swept about 100 feet into a shallow crevasse which sheltered him from the avalanche. He estimated that our two companions on the lead rope were immediately below the full weight of the avalanche and so must be dead.

We limped through the semi-darkness of midnight toward the area of advanced base camp, and the food cache. There we saw a tent, pitched rather limply to be sure. Our companions were there. We spoke in low tones like shell-shocked veterans of combat. They had been rolled two hundred feet as we had, but in addition had been pelted by blocks of ice so that each looked and felt as though he had been destroyed in a fist fight. One appeared to have a broken rib. Neither was sure he could walk in the morning. There was more bad news. We had lost both stoves and so had no water. Our canteens were, of course, empty; we paid dearly for our haste in the morning.

After five hours of fitful sleep, we awoke to see intermittent white-outs on the glacier, which would slow our descent. The first leg took us to 9,000 feet where we expected to find a scientist from the University of Alaska ready to study our physiology while we studied his stove. He was not there. We did find 'C' rations, however. This was most important because the canned food was moist. Some of the fruit had much juice. The next soldier to complain about 'C' rations will have to deal with me! Never has food tasted more delicious. We each ate three meals in succession. Our strength was significantly restored by these delicacies and all felt they could hike to base camp.

Bedeviled by white-out, we did not quite make it to base camp. By 9 p.m. we had reached a pond of melted snow on the main Kahiltna glacier at 6,500. This would sustain life, as eating snow would not. All felt immense relief and certainty of survival as we drank quart after quart of powdered milk.

We slept for fourteen hours, then moved to base camp to await the glacier pilot in comparative comfort. Three weeks after leaving the mountain, we learned that our two other routes had been successful. The Cassin Ridge had yielded to our leader, Boyd Everett, and four others. The new South Face route, perhaps the most difficult of its kind in North America, was conquered by three Dartmouth men, Graham Thompson, Dennis Eberl and David Seidman, and a Fordham student, Roman Laba.

This account, because it features a near disaster, will not do much to clarify the appeal of this kind of mountaineering. One source of appeal is the simplicity of the task. How many times in life does an adult have just one purpose to pursue without interruption for five weeks? No telephone rings to tell you of a dozen conflicting obligations. When confined to the tent by storm only three objects command your attention: book, cup, and spoon. The greatest material loss imaginable is the loss of one's cup. Life is, for a time, simplified.

The second source of appeal of expedition mountaineering is the stunning beauty of the surroundings. Numerous picture books document the point, obviating further comment.

The hazards are numerous. Many are avoidable. It would appear from what little information is available, that the seven members of the Wilcox expedition who probably died on the North side, while we were climbing the South side, took unnecessary risks in reaching the summit. Certainly the weather was not exceptional for the time of year. Most mountaineers think, or deceive themselves into thinking, that they avoid unnecessary risks. But what of our accident? It was utterly arbitrary of the mountain to come crashing down at that time. Why not a day earlier or a day later? There are some factors in the mountains, particularly snow peaks, which you cannot control. One's enthusiasm for climbing them must inevitably be diminished by an experience such as ours. Death in such circumstances would be so futile, such a waste.

Horan on McKinley's summit.

Jim Janney '69 of Frontenac, Mo., shoving some signs of the battering he tookfrom the severe avalanche.

Michel Zalewski '68 at 19,000 feet

David Seidman '68 (left) and Paul Kruger '6B at 11,500 feet. Seidman was a memberof the party that climbed the hazardous South Face route for the first time.

TONY HORAN, son of Francis H. Horan '22, originally wrote his article, in very much its present form, for The Lakeville (Conn.) Journal, which has kindly given permission For reprinting it. Young Horan is now serving in Vietnam as a medical captain with we U.S. Air Force.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Fulbright Professor in France

November 1967 By FRANCIS E. MERRILL '26, -

Feature

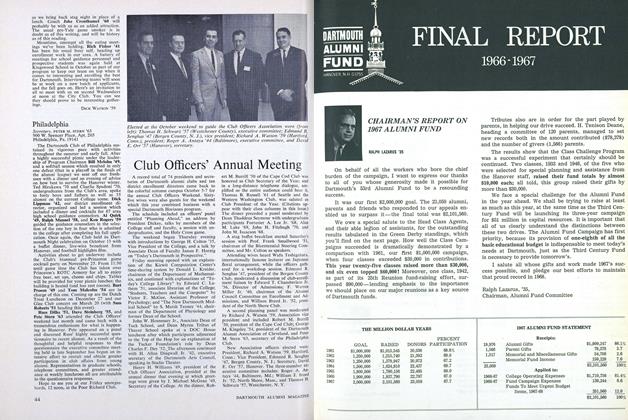

FeatureFINAL REPORT 1966-1967

November 1967 By RALPH LAZARUS '35 -

Feature

FeatureTHE BETRAYAL OF IDEALISM

November 1967 -

Feature

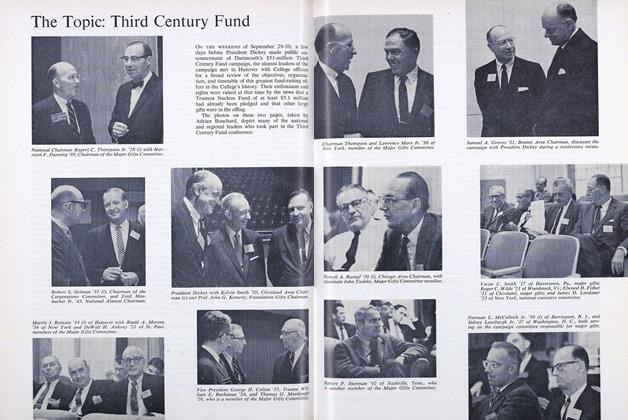

FeatureThe Topic: Third Century Fund

November 1967 -

Article

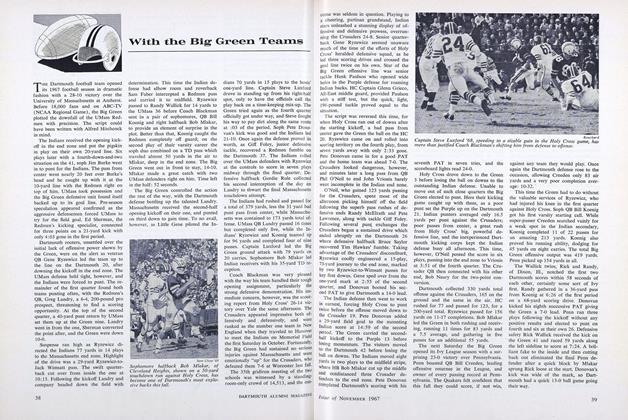

ArticleWith tine Big Green Teams

November 1967 -

Article

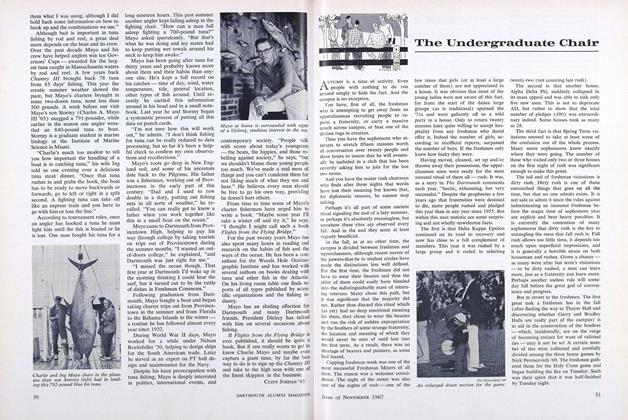

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

November 1967 By JOHN BURNS '68

Anthony H. Horan '61

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Medical School

April 1975 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryFred McFeely Rogers 1950

NOVEMBER 1990 -

Feature

FeatureCue the Millennium

NOVEMBER 1996 -

Feature

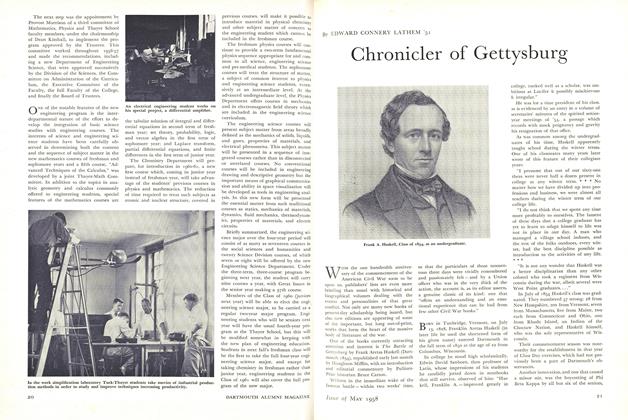

FeatureChronicler of Gettysburg

May 1958 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

FeaturePersonal History

May/June 2010 By JOE BABCOCK ’08 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO CONVINCE YOUR CLASSMATES TO FORK IT OVER

Jan/Feb 2009 By TROY STEWART '07