In simplest terms, the consuming preoccupation - personal and professional - of RALPH W. BURGARD '49 is bringing people and the arts together.

Of those "certain unalienable rights" with which men were endowed by their Creator - a truth proclaimed self-evident in the Declaration of Independence - some have fared better than others, in the estimation of Burgard, an arts consultant and former director of the Associated Councils of the Arts.

Despite praiseworthy strides since 1776 toward securing Life and Liberty, the Pursuit of Happiness has been badly neglected, he contends. "We are reaching that point when we're beginning to ask 'What are we doing all this for? What is the good life?' The response to these questions is the ultimate test of a country; above all others, it will stamp us as a great nation or a failure."

Bringing the arts - and the sciences - down from their pedestal and into the current of daily life Burgard sees as a key to implementing the pursuit of happiness, to elevating the quality of life. And the accent is on participation. "The creative instinct is in everyone, regardless of intelligence or education. People are demanding involvement, and participation in the arts gives them a way to express themselves in an impersonal world."

Burgard's consulting work focuses on two major areas: organizing conferences and seminars wherein small groups of decision makers can discuss issues and shape policy for the dissemination of the arts; and working with governmental or community agencies or private interests to coordinate existing resources and develop new ways to bring people and the arts together.

For the cultural ministries of Holland, Sweden, Great Britain, France, and the United States, he set up in 1971 the Dartington Seminar on Cultural Decentralization, which brought 20 art administrators and specialists from the five countries together for a week of intensive talk at a rural English manor house. A series of seminars, supported by the National Endowment for the Arts, has assembled representatives of New Towns in the U.S. and Canada to discuss the need to integrate the arts into their planning and programming.

Burgard has two immutable principles in accepting commissions: he will take on no more than he can effectively follow through personally from initial interviewing to final report; and he will undertake no project for which he can't raise funds. "No matter how good a plan, it's worthless without support."

Among his current projects is the development of a plan to convert the state-owned Fort Warden, Wash., into a "center for creativity." Another is a cultural plan for Jacksonville, Fla. Yet another is the coordination of a cultural program for a private development in Fort Lauderdale, where an upper-level pedestrian mall will incorporate shops, a skating rink, a concert hall, art and cience museums, a library, a sports arena, TV studios, a restaurant, a health clinic, and a walk-in crafts center. Burgard's vision of the ideal integration of commerce and culture, of spectatorship and participation, it represents the same "casual encounter" with the arts he finds so admirably exemplified in the Hopkins Center.

A burgeoning national interest in the arts Burgard attributes to America's maturing. Pioneer life left little time for the arts, he points out, and the cultural institutions of Europe, established for the most part under royal patronage, did not transplant well. With the fundamental work of building a nation behind them, Americans began to put down artistic roots and to realize the rich cultural heritage of ethnic diversity and indigenous forms. He predicts a bright future, with sophisticated electronic devices playing an increasing role on the participatory as well as the spectator level.

The 1976 Bicentennial, which Burgard believes must be celebrated "with a dutiful look at the past, but a much firmer look to the future," has already called attention - and brought badly needed financial resources - to the arts. While he would welcome more government support for the arts in general, he sees as optimal "a combination of public and private funds, utilizing the best of both," the advantage of the latter being flexibility, readiness to risk.

Burgard came professionally to the arts, after a brief fling in advertising, through orchestra management in Providence and Buffalo. He was director of the Arts Council of Winston-Salem, N.C., and the St. Paul Council of Arts and Sciences, both of which built arts centers and inaugurated united arts fund drives under his tenure, before going to New York in 1965 as first director of the Associated Councils of the Arts.

He writes as indefatigably as he promulgates the need for the arts in every life. Numerous articles and a book Arts in the City will be followed shortly by a volume on arts programs for the suburbs. He is an ardent balloonist, having learned the sport from Jean Piccard in Minnesota. In Hanover occasionally as an Overseer of the Hopkins Center, he has never topped for drama a balloon ascension from the Green to celebrate Dartmouth's Bicentennial in 1969.

When Ralph Burgard left Winston-Salem, a regretful editorial praised his "rare combination of a business head and an artistic heart." An invaluable asset in an evangelistic advocate of the pursuit of happiness through the arts.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureSailing Dreams and Random Thoughts

March 1973 By JAMES H. OLSTAD '70 -

Feature

FeatureNotes Towards a "Whole Life Catalog"

March 1973 By ALAN T. GAYLORD, DIRECTOR -

Feature

FeatureTHE ACRONYM SYNDROME

March 1973 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

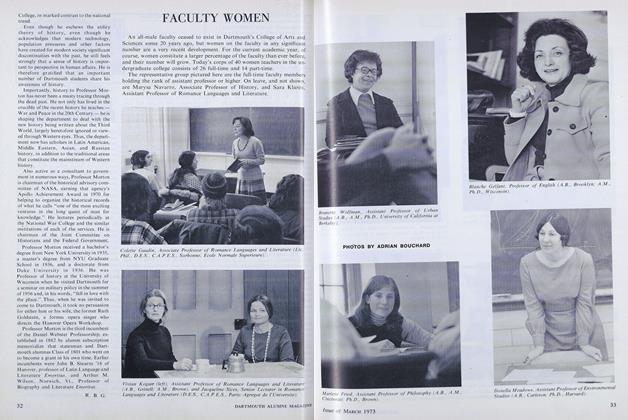

FeatureFACULTY WOMEN

March 1973 -

Feature

FeatureUNDERGRADUATE JOURNAL

March 1973 -

Article

ArticleBrautigan's Search for Reality

March 1973 By RICHARD D. CARYOLTH '73

MARY ROSS

-

Feature

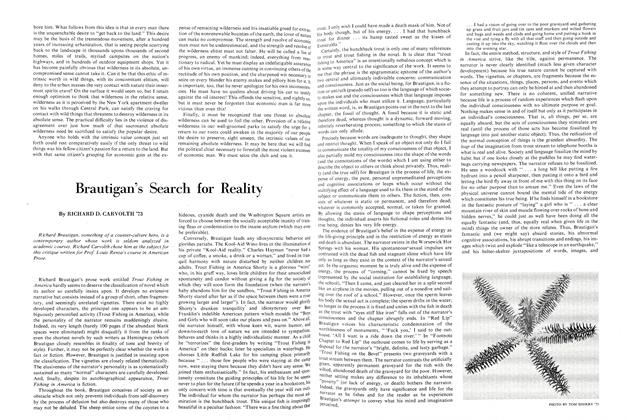

FeatureAnti-Bigot

JANUARY 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Article

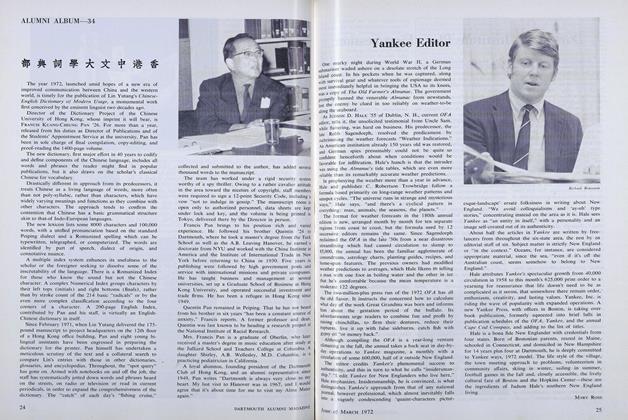

ArticleYankee Editor

MARCH 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Article

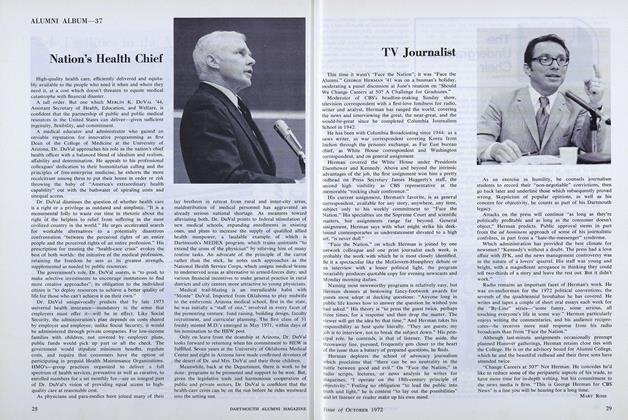

ArticleTV Journalist

OCTOBER 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Article

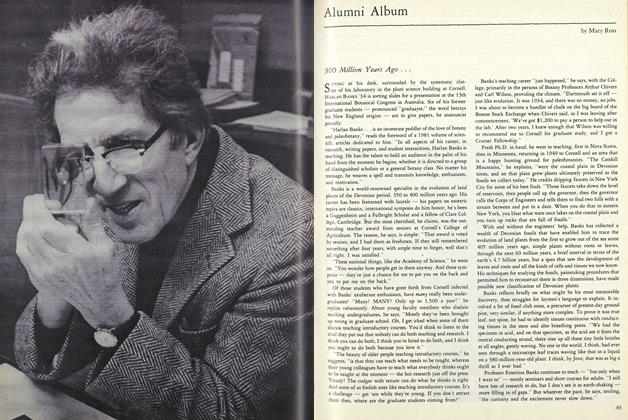

Article300 Million Years Ago . . .

NOVEMBER 1981 By Mary Ross -

Article

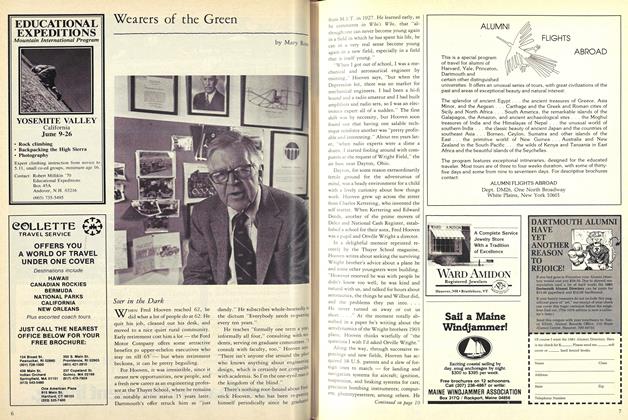

ArticleSeer in the Dark

APRIL 1982 By Mary Ross -

Article

ArticleBob Blackman: Tackling Retirement in Hilton Head

SEPTEMBER 1984 By Mary Ross

Article

-

Article

ArticleCOLLEGE NOTES

August, 1915 -

Article

ArticleCONGRATULATIONS

March 1935 -

Article

ArticleNorth Country Fair

April1935 -

Article

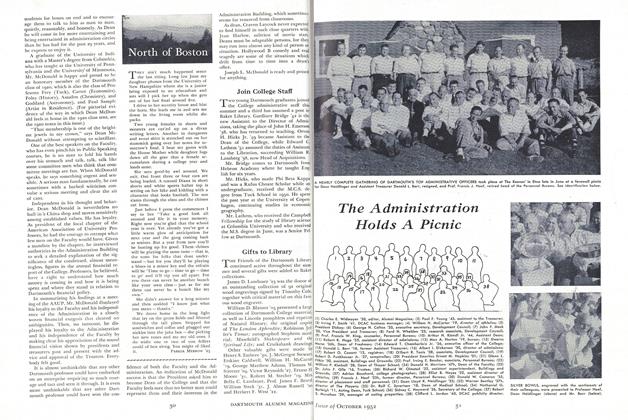

ArticleThe Administration Holds A Picnic

October 1952 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

November 1961 By DAVE SCHWANTES '62 -

Article

ArticleSlow Tomatoes, Cajun Cooking, ana Crime

APRIL 1997 By Professor George Demko