Either a bold move to throw the rascal out or, according to a cabinet member, "a conspiracy to overthrow the government," the trial of Andrew Johnson was a bitter episode for the nation. Afterward Thaddeus Stevens, arch-enemy of the President and one of four Dartmouth men involved, predicted im- peachment would never be attempted again.

One of the truly traumatic episodes in American history reached its crisis on March 5, 1868, when Chief Justice Salmon Portland Chase, Dartmouth 1826, solemnly and with deliberate step, entered the Senate Chamber. The Chief Justice, more than six feet tall, with handsome features, massive frame and majestic bearing, was flanked by Samuel Nelson, senior Associate Justice of the Supreme Court, and escorted by Senators Charles Buckalew of Pennsylvania, Samuel Pomeroy of Kansas, and Henry Wilson of Massachusetts, a committee named for that purpose by the President pro tempore of the Senate, Benjamin Franklin Wade of Ohio. "Honest Ben" Wade would succeed to the Presidency should the business at hand terminate as he and his fellow Radicals anticipated.

The Chief Justice, his deep-set blue-gray eyes grave and commanding, accepted the chair from Wade and announced in his clear, resonant voice, "Senators, I attend the Senate in obedience to your notice, for the purpose of joining with you in forming a court of impeachment for the trial of the President of the United States, and I am now ready to take the oath." Nelson promptly administered a judicial oath, which was then taken by each of the 54 men who at that time constituted the Senate of the United States. The maneuver caught the Senators off guard, for few of them had considered the Chief Justice as more than a pro forma presiding officer who was there only because the Constitution required it and'who was not in any sense to be considered as a member of the court. Even the court itself was a departure from the views of most of the Senators, who had never doubted that they would try Andrew Johnson under their own familiar rules for the "high crimes and misdemeanors" alleged in the articles of impeachment. Yet before they had time to object, the Chief Justice (who had once been a member of that club himself) had transformed them into a court of law, to function under procedures of which he. not they, would be the judge.

Among the "jurors" thus sworn was James Wilson Grimes, the straight-forward, unassuming, "no nonsense" Senator from Iowa who had left Dartmouth in mid-career to study law, but had been awarded a diploma with the Class of 1836. At the age of 22 Grimes had chaired the Judiciary Committee in the first Legislative Assembly of lowa Territory. He had gone on to the State Legislature and to the Governorship before his election to the Senate in 1858. Another was James Willis Patterson, Dartmouth 1848, minister, lawyer, educator and still, in absentia, a member of the Dartmouth faculty though he now represented his native New Hampshire in Washington. Also among the Senators were William Sprague of Rhode Island, son-in-law of Chief Justice Chase; David T. Patterson of Tennessee. son-in-law of President Andrew Johnson; and leader of the conservative Republicans, William Pitt Fessenden of Maine, whose father, Samuel Fessenden, Dartmouth 1806, had been a lifelong friend of Daniel Webster and who was himself Webster's godson and political protege.

Watching from seats reserved for members of the House, and missing nothing despite the ravages of age and disease, was the man primarily responsible for the impeachment and trial, Thaddeus Stevens, Dartmouth 1814, who represented Lancaster, Pa., in the lower house. Though he held no party office, indeed was personally disliked by many of his fellow Republicans, he controlled that body by the sheer force of his will and the strength of his convictions. "The country is in the hands of Congress," wrote a reporter for the New York Herald. "That Congress is the Radical majority, and that Radical majority is old Thad Stevens."

The four Dartmouth men who participated in the impeachment trial of An-drew Johnson had little else in common save that all were strong antislavery men. Chief Justice Chase, during the years that he practiced law in Cincinnati, had been known as "attorney for the runaway slaves." He had first entered public life as an abolitionist, and as Secretary of the Treasury in Lincoln's cabinet had helped to draft the Emancipation Proclamation. One of his first acts as Chief Justice was to admit the first Negro ever to practice before the Supreme Court. Grimes and Patterson, although less singleminded in the cause, had been throughout their careers consistent opponents of slavery. Thaddeus Stevens, now 76 years old and fatally ill, remained the very embodiment and personification of the abolitionist cause, and the foremost political champion of the Negro. Born with a clubfoot, he walked always with a limp that half-belied his raw-boned, six-foot frame, but he fooled no one by the tousled, oversized brown wig that covered his total baldness. He was often bitter, frequently caustic, a master of invective, tenacious in pursuit of his goals and immovable in his convictions. The Herald reporter put. it in popular terms, but the truth was that Thad Stevens, acknowledged leader of the Radical wing of the Republican Party, wielded more power than any other in- dividual in the United States, including the President.

The Senate - or rather, the Court of Impeachment - met sporadically during the month, allowing time for the lawyers to study the charges and prepare their briefs. Then, on March 30, 1868, began the trial of Andrew Johnson, President of the United States, on 11 articles of impeachment voted by the House of Representatives.

The events leading up to this first impeachment of a President of the United States were at once obvious and complex, an amalgam of clashing personalities, sharply different backgrounds, ideologies, concepts of the nature of the Union, and racial attitudes. Andrew Johnson, self-educated "poor white" from the mountains of eastern Tennessee, owed his position to three factors: he was a Democrat, which had given a non-partisan cast to the Lincoln ticket of 1864; he was the only Southern Senator who had denounced secession and retained his seat when his state left the Union; and he had been phenomenally successful as military governor of Tennessee in bringing that state, though still occupied by Union forces, back to its ancient national allegiance. His lifelong dislike and distrust of the aristocratic planter caste of the South endeared him to Northern abolitionists, who never bothered to ascertain how Johnson personally felt about slavery and the Negro. When, on his accession to the Presidency, he pledged what seemed a "tough" Reconstruction policy, he received general support from the Radicals - even from Stevens, though with many qualifications.

Johnson's Reconstruction policy had been foreshadowed by his administration of Tennessee. Indeed, it had been outlined by President Lincoln himself, although Johnson would presently introduce modifications of his own. Lincoln had from the very beginning of his Presidency denied that any right of secession existed, under the Constitution or outside of it. The people of the 11 states that formed the Confederacy were in rebellion; they had of their own free will withdrawn their representatives from Congress; undeniably their relationship to the United States was - temporarily - abnormal. But Lincoln and Johnson both insisted that they remained members of the Federal Union to be restored to the old basis as soon as the rebellion was crushed and new loyal state governments could be formed. These new governments were to be chosen by individuals who would be pardoned upon taking an oath of allegiance to the United States, providing they constituted at least ten per cent of the qualified voters of 1860. Neither Lincoln's Proclamation of December 8, 1863, nor Johnson's of May 29, 1865, mentioned Negro suffrage or civil rights for the freed slaves; and Johnson's omitted any reference to ten or any other percentage of voters who must take the loyalty oath.

Both Lincoln and Johnson, moreover looked upon reconstruction of the defeated South as a Presidential responsibility, although Lincoln freely conceded that the Congress could override the results for any given state simply by refusing to seat the Senators and Representatives so chosen. Johnson seemed to feel that Congress was bound to ratify whatever resulted from his policy. To his narrowly rigid mind, the details of Reconstruction were a function of the states. Since they had not actually left the Union, they retained all of their local prerogatives - the state rights so dear to the antebellum South. Johnson's own earlier reconstruction in Tennessee had been carried out by the state and ratified by a popular majority of her people. So he believed it should be in every case, and he set himself to make it so before the Congress reconvened in December.

Over the summer and fall of 1865 the President very nearly did just that. The former Confederate states, by the spring of 1866, had all adopted new constitutions, abolished slavery, and repealed their ordinances of secession. All but South Carolina had repudiated the Confederate debt, and all but Mississippi had ratified the 13th Amendment putting a final end to slavery. Not one of those new constitutions granted to the former slaves a right to vote, and all of them contained police regulations ostensibly to keep order among the freedmen but in fact as harsh as the old slave codes. The old institution of slavery was in effect simply transferred from an individual to a community basis. Senators and Representatives had been chosen - the latter in greater numbers than before the rebellion because each black now counted as one man in the apportionment, instead of the old federal ratio of three-fifths of a man. Those so elected were of the same class, and often enough the same individuals as before the unpleasant hiatus of the past four years, and they were most of them in Washington ready to take their seats when Congress reconvened on December 4, 1865.

The Radical Republicans could hardly be blamed for their passionate rejection of this most distasteful result of Presidential Reconstruction. The country had just passedthrough a bloody and destructive civil war - a war that had been in the making since the tariff controversies of the 1820s and the beginnings of the antislavery movement around 1830. Increasingly after the Mexican War, slavery had come to be the overriding national issue. It was given a new militancy in the 1850s by the Kansas-Nebraska act which repealed the Missouri Compromise and offered the fertile plains of the transmississippi west to the labor of slaves; and by the Dred Scott decision of the Supreme Court which swept away the power of Congress to exclude the reprobated institution from any territory of the United States. Slavery was an issue _ sometimes tacit, sometimes overt _ in the Presidential campaign of 1860, and its abolition was in the eyes of countless Northerners the only reason for the bitter struggle that absorbed the years between Sumter and Appomattox, at a cost of half a million lives. The controlling majority in Congress were themselves old abolitionists or were the spiritual descendants of .such, fully committed to the destruction of slavery when the war began, and before it ended equally committed to full citizenship, including the suffrage, for the former slaves. It was they who had forced Lincoln's hand on abolition, and who used their power to keep the President on the track.

The newly elected Senators and Representatives from the former slave slates were promptly disqualified and their seats were allowed to remain vacant throughout the 39th Congress and the first session of the 40th. The next step was for Congress to formulate its own program of Reconstruction. A joint committee for that purpose was set up, chaired by the relatively moderate Fessenden but dominated by Stevens. The ultimate product was the 14th Amendment, adopted by Congress in June 1866, but on the way to this result the chasm between Congress and the President became unbridgeable.

A bill enlarging and extending the powers of the Freedmen's Bureau, including a provision of doubtful constitutionality for enforcement of civil rights by military tribunals narrowly failed of passage over the President's veto. The same purposes were accomplished by a civil rights bill, passed over the veto on April 9. This act was in effect a blunt warning to the states not to interfere in any way with the full rights of citizenship bestowed upon the Negro. If there were constitutional objections, they were to be removed by the 14th Amendment.

The Joint Committee on Reconstruction, meanwhile, had reported at length and in detail, advancing a position completely at variance with the Lincoln-Johnson theory that the rebellious states could not secede and therefore had never actually been out of the Union. The committee report argued that the states in question, by withdrawing their representatives from Congress and levying war against the United States, had forfeited all political rights and were thenceforth to be treated as conquered provinces. Congress alone was to determine when they were to be readmitted to national representation. The quid pro quo was to be ratification of the 14th Amendment, but for the time being only Tennessee complied.

In the fall elections of 1866 the Radical Republicans won an overwhelming victory, which they interpreted quite naturally as a mandate to proceed with their announced policies. Reports of atrocities inflicted upon blacks in the Southern states were too persistent to be ignored. Indeed, they were amply attested by so objective an observer as Carl Schurz. The evidence that the freedmen were being systematically denied the rights Congress had granted them was overwhelming. The newly established Ku Klux Klan stood as an ominous denial of all the war aims of the Radicals. Again under Stevens' leadership, Congress exercised its mandate by passing two Reconstruction acts early in 1867, substituting military government in the Southern states for the local home rule by ex-Confederates that had come out of policy. The President vetoed both acts and both passed over the veto.

Johnson, by his execution of the Congressional policy, did all in his power to nullify it, but the actual administration of military government fell necessarily to the War Department, and the Secretary of War, Edwin M. Stanton, was one of the Radicals, held over from Lincoln's cabinet. Stanton not only followed out the intent of Congress - he served the Congressional majority as a spy in the enemy's camp. The now beleaguered President sought to outmaneuver both the Congress and his War Secretary by his appointments of commanders for the military "occupation" but again Congress thwarted him by giving the appointments, in a third Reconstruction act, to the commanding General of the Army.

As a further device for protecting its own power Congress had meanwhile passed, again over the veto, a Tenure of Office Act, which forbade the President to remove appointed officials except with the consent of the Senate. The House had also considered the possibility of impeachment, but rejected it because no one, not even Stevens, believed that any high crime or misdemeanor, within the meaning of the Constitution, could be proved.

Then Johnson offered the necessary cause. He removed Stanton from office in August 1867, when the Senate was not in session. In December, when Congress reconvened, the Senate rejected the removal, and Stanton returned to the War Department. Johnson removed his disloyal Secretary once more, and two days later, on February 24, 1868, the House agreed to impeachment. The vote was 128 to 47. There were 11 articles of impeachment, the Nth prepared by Stevens being a recapitulation of the others, but the only one that appeared to have legal validity was violation of the Tenure of Office Act.

Such was the background leading up to the trial that opened in the Senate Chamber, March 5, 1868. The real point at issue was not a specific violation of a particular act of Congress but a very fundamental difference as to how a military conquest was to be converted into a political victory; or more precisely, how the objectives of a successful war were to be imposed upon the losers. The Congressional leaders were men who believed, each to the very core of his being, not only in freedom but in full political equality for the Negro. To them the war had been fought to achieve this end, and all its sacrifices were in vain if the freedmen were now abandoned to the tender mercies of their former masters, or if the enlarged representation given by abolition to the Southern states should permit them to dominate national policy.

Andrew Johnson was equally honest and equally sincere in his convictions, but he had lived his life in a slave-based society, had been himself a slaveholder, and could not believe that the black man, even though no longer in bondage, was capable of participating in the processes of government. Johnson had begun his own political career as an opponent of the plantation aristocracy. A tailor by trade, he had suffered too much at their hands to trust any of them. Yet as he sought to advance his own plan of Reconstruction in the face of rising Congressional opposition, he found that he must now make common cause with those he once despised. That he was able to do this is some measure of tribute to the strength of his own convictions.

When the Senate-as-court resumed its deliberations on March 30, the members were concentrated in two rows, leaving the rest of the chamber for members of the House. Counsel for the President sat at the right of the Chair, impeachment managers for the House to the left. They were indeed an imposing group. The seven House managers were Stevens; Benjamin Franklin Butler, newly elected Congressman from Massachusetts, who as general of the Union forces occupying New Orleans had earned the name of "Beast"; George Sewall Boutwell, also from Massachusetts, who as a member of the Joint Committee on Reconstruction had helped to frame the 14th Amendment; John Armor Bingham of Ohio, not fully convinced himself; John Alexander Logan of Illinois, a former Democrat, who had no doubts; Thomas Williams, another Radical Republican from Pennsylvania; and James Falconer Wilson of lowa, generally but not always radical.

The President, who declined to appear in person, was represented by a most distinguished quintet, headed by Henry Stanbery, successful Ohio lawyer who had resigned as Attorney General of the United States to defend the President. Best known of the five was Benjamin Robbins Curtis, eminent Boston attorney who, at the instigation of Daniel Webster, had been named by Millard Fillmore to the Supreme Court. His had been one of the two dissents in the Dred Scott case, argued for the plaintiff, incidentally, by his brother, George Ticknor Curtis, in what today would be considered a flagrant conflict of interest. As if that were not enough. Judge Curtis published his opinion before it was read in court. Chief Justice Taney saw it, and rewrote his own opinion to answer Curtis' points. Over the ensuing controversy, Curtis had resigned. Also of the President's counsel were Thomas A. R. Nelson, like Johnson himself a Tennessee Unionist; William Maxwell Evarts, brilliant New York lawyer who would serve as attorney general under Grant and as Secretary of State in the Cabinet of President Hayes (and who, in another historical irony, was the great-grandfather of Archibald Cox); and William J. Groesbeck of Ohio, a last minute replace- ment for Jeremiah S. Black, disqualified.

Of all the charges, grave or trivial - and most were trivial - named in the articles of impeachment, only the violation of the Tenure of Office Act could be made to stand up. Even that would fall down unless impeachable offenses could be so defined that an indictable crime was not necessarily required. William Lawrence, a former Ohio judge and now member of Congress had prepared an elaborate and learned brief of authorities on impeachable crimes and misdemeanors, which Butler, opening for the prosecution, used:

"We define, therefore, an impeachable crime or misdemeanor to be one in its nature of consequences subversive of some fundamental or essential principle of government, or highly prejudicial to the public interest, and this may consist of a violation of the Constitution, of law of an official oath, or of duty, by an act committed or omitted, or, without violating a positive law, by the abuse of discretionary powers from improper motives or for any improper purpose.

Curtis, who led off the defense, had been all but canonized by the Radicals themselves for his dissent in the Dred Scott case. The defense, addressing itself to the only solid article in the impeachment, contended that the Tenure of Office Act was unconstitutional, and that it did not apply to Stanton anyway. He had been appointed not by Johnson but by Lincoln and Lincoln's successor, in the absence of any reappointment by himself, was therefore free to remove him at will. As the trial progressed, each contention of the prosecution rested in the end as it had in the beginning on a definition of impeachable offenses.

Stevens, visibly ill, insisted on bearing his share of the argument. He began reading a prepared brief in a voice barely audible, but was soon unable to continue. Butler finished the reading of what was the shortest speech of the whole trial. "Thus it is apparent," Stevens summed up, "that no crime containing malignant or indictable offenses higher than misdemeanors was necessary either to be alleged or proved. If the respondent was shown to be abusing his official trust to the injury of the people for whom he was discharging public duties, and persevered in such abuse to the injury of his constituents, the true mode of dealing with him was to impeach him for crimes or misdemeanors....

"When Andrew Johnson took upon himself the duties of his high office he swore to obey the Constitution and take care that the laws be faithfully executed. That, indeed, has always been the chief duty of the President of the United States. The duties of legislation, and adjudicating the laws of his country fall in no way to his lot. To obey the commands of the sovereign power of the nation, and to see that others should obey them, was his whole duty - a duty which he could not escape, and any attempt to do so would be in direct violation of his official oath; in other words, a misprison of perjury.

"I accuse him in the name of the House of Representatives, of having perpetrated that foul offense against the laws and interests of his country."

Stevens discussed the Tenure of Office Act; then went on to name other "misdemeanors" of which he held the President guilty. He did not elaborate. it would have accomplished nothing if he had. For the charges he now brought were not included in any of the articles of impeachment. The President, Stevens now charged, "had passed away unnumbered millions of the' public property to rebel railroad companies"; he had "stripped the Bireau of Freedmen and Refugees of its munificent endowment, by tearing from it the lands appropriated by Congress to the loyal wards of the republic, and restored to the rebels their justly forfeited estates"; he had plundered the Treasury "for the benefit of favored rebels by ordering the restoration of the proceeds of sales of caplured and abandoned property which had been placed in its custody by law"; and he had grossly abused the pardoning power by "releasing the most active and formidable of the leaders of the rebellion with a view to their service in the furtherance of his policy."

The long drawn contest between President and Congress, already of three years' standing, was now hurrying to a close. The Republican national convention, which was to nominate General Grant for President, was scheduled to meet in Chicago on May 20, yet the impeachment trial, it appeared, would still be going on.

It was May 16 when the first vote was called, by common consent on Article XI before any of the others. Senator Fessenden asked for a delay because his friend Senator Grimes of lowa, one of the two Dartmouth Senators, was not in his place. Grimes had suffered a stroke three days earlier, but he had already been summoned, in anticipation of the vote, and was then in the Capitol. A few minutes later he was carried to his seat.

The Senators were then polled in alphabetical order, each individually, by the Chief Justice. Most had long been committed, so that their responses offered nothing of surprise. Grimes pulled himself to his feet, and by a mighty effort of will stood erect to vote. Though he reprobated the President and all his works, he refused to accept Johnson's derelictions as "high crimes and misdemeanors" and voted to acquit. The other Dartmouth Senator, Patterson of New Hampshire, had been convinced from the beginning and voted conviction. The only doubtful Senator was Edmund Ross of Kansas, who had hitherto kept his own counsel. When his name was called he voted for acquittal, and for all practical purposes the trial was over. The final count on Article XI was 35 to convict against 19 to acquit - one vote short of the necessary two-thirds.

Wade, though his right to vote was Questioned on grounds of self-interest, gave his voice for conviction. He was as fanatical as Stevens, and it was freely said that some voted to acquit Johnson only because they felt Wade would be worse.

The Senate then adjourned until May 26, while the Republicans attended their party convention. When the court reassembled votes were taken on the first three articles, all ringing changes on the Tenure of Office theme, but with the same result as on Article XI. By tacit agreement the trial was halted there and the President declared not guilty of the high crimes and misdemeanors charged in the impeachment. His term had less than a year to run; his hands were already tightly bound, and Reconstruction was proceeding according to the formula of Thaddeus Stevens and the Radical Republicans. With one crucial omission: Stevens had realized from the start that the freedmen could not hold their own without an economic stake, and he had sought unsuccessfully to provide them with land carved from the old plantations.

The impeachment and trial of Andrew Johnson has been treated as a colossal blunder, brought about by a clash of wills to the detriment of the country; and it has been defended as a necessary step to consolidate the military victory. There were in fact two major points at issue: Did impeachment require an indictable offense? Was the Congressional plan of Reconstruction so far superior to the President's as to justify any means to impose it? The second question, from the perspective of a century later, is tragically ironic, for neither program achieved - or offered to achieve - the full integration of the Negro that is still somewhere in the hopeful future.

To the first question, the overwhelming weight of evidence from the Federalist on through the commentaries that preceded the event was that impeachment did not require any offense for which a criminal indictment might be returned. It was and remains the grand inquest of the Republic by means of which a Chief Executive may be held accountable for the faithful performance of his duty. That Johnson had failed at many points now seems clear, especially in his reluctance to implement the civil rights act, and in his willingness to return the control of the Southern states to those who had defied the Constitution by secesion and were even then evading the Reconstruction acts.

The truth is, Andrew Johnson was impeached on the wrong grounds, a mistaken judgment for which Dartmouth's own Thaddeus Stevens must be held primarily responsible. Perhaps even on the right grounds - Johnson's refusal to carry out the war aims, particularly as far as Negro rights were concerned - a conviction could not have been obtained, given all the circumstances of the time; but if it had, a precedent would be securely established for a broad interpretation of the still controversial "high crimes and misdemeanors."

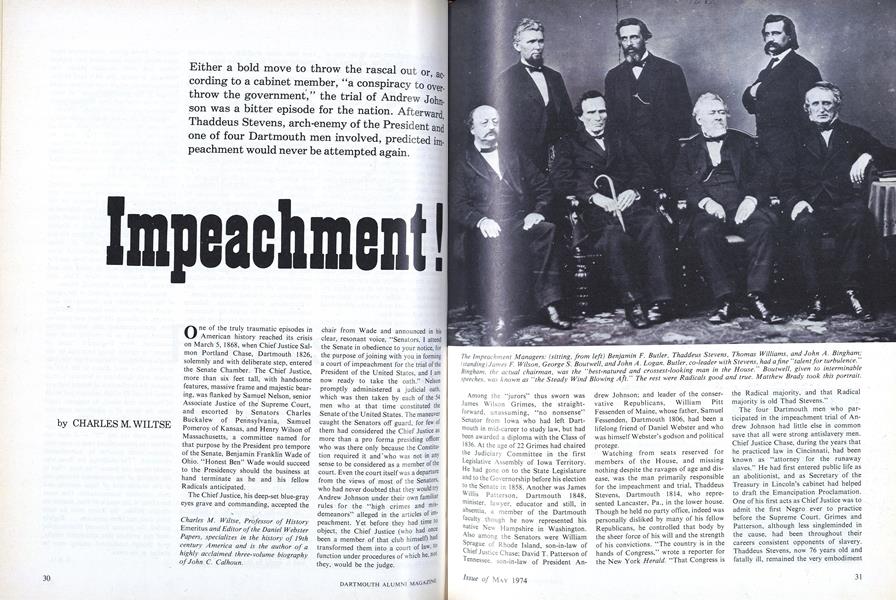

The Impeachment Managers: (sitting, from left) Benjamin F. Butler, Thaddeus Stevens, Thomas Williams, and John A. Bingham;(standing) James F. Wilson, George S. Boutwell, and John A. Logan. Butler, co-leader with Stevens, had a fine "talent for turbulence."Bingham, the actual chairman, was the "best-natured and crossest-looking man in the House." Boutwell, given to interminable speeches, was known as "the Steady Wind Blowing Aft." The rest were Radicals good and true. Matthew Brady took this portrait.

Thaddeus Stevens (above), Dartmouth1814, once referred to President Johnsonas "that drunken tailor at the other end ofthe avenue." For waspish Old Thad impeachmentwas a no-holds-barred battle tobe fought against a malevolent Chief Executive who obstructed the will of the people- and Congress - and who en-dangered the destiny of six million formerslaves. Stevens spent 30 years in the Houseof Representatives and became "thegreatest dictator Congress has ever had."

James W. Grimes (below), Dartmouth1836, writing to a friend in lowa shortlybefore ,the storm broke, prophesied, "Itwill be the greatest trial in history, but Iwish to Heaven that I had nothing to dowith it. ..." Grimes was a Republican, butdetested Stevens as a "debauchee inmorals and politics." The lowa Senatorplaced a strict construction on impeach-ment and found no indictable crimes in thePresident's behavior. In a dramatic courtroom appearance he voted "not guilty."

Salmon Portland Chase (above), Dartmouth 1826, was opposed to impeachmentand was accused of working behind thescenes to save Johnson, thereby earningthe abuse of the Radicals. According toBen Wade, the Chief Justice regardedhimself as the fourth person in the Trinity,and it was true he felt the country deservedhis election to higher office. He wantedthe Republican nomination in 1864 (afterresigning as Lincoln's Secretary of theTreasury) and in 1868, but lacked support.

James W. Patterson (below), Dartmouth1848, was solidly in favor of impeachment.As a teacher of astronomy at the College,his qualifications had been suspect, but theundergraduates thought him the bestorator of the day. In a speech during theCivil War, one student reported. Pattersonbecame so "fired up ... that his language... was the most eloquent I ever heard fallfrom mortal's lips. How the boys did cheerhim!" Patterson's political career endedunder the cloud of the Credit Mobilier.

The House debate ended with Stevensdemanding impeachment and imprisonment.On the deciding first ballot the votewas 126-47 to bring Johnson to trial.

An 1868 sketch from Harper's Weekly shows Johnson receiving the impeachmentsummons. The beleaguered President prom-ised that he "would attend to the matter."

Stevens, weak and trembling but driven byengulfing determination, enters the Senatechamber on the opening day of the trial.Wade and the other Radicals follow him.

Charles M. Wiltse, Professor of History Emeritus and Editor of the Daniel WebsterPapers, specializes in the history of 19thcentury America and is the author of ahighly acclaimed three-volume biographyof John C. Calhoun.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

CHARLES M. WILTSE

-

Books

BooksJOSHUA R. GIDDINGS AND THE TACTICS OF RADICAL POLITICS.

OCTOBER 1970 By Charles M. Wiltse -

Books

BooksTHE HEALING OF A NATION.

OCTOBER 1971 By CHARLES M. WILTSE -

Books

BooksTHE PAPERS OF ADLAI STEVENSON.

January 1974 By CHARLES M. WILTSE -

Article

ArticleWebster and a Small College

April 1974 By CHARLES M. WILTSE -

Books

BooksTHE PAPERS OF ADLAI E. STEVENSON. VOL. 4. LETS TALK SENSE TO THE AMERICAN PEOPLE." 1952-1955

July 1974 By CHARLES M. WILTSE -

Books

BooksA Strong and Hungry Spirit

June 1975 By CHARLES M. WILTSE

Features

-

Feature

FeatureFor Distinguished Service . . .

JULY 1959 -

Feature

FeatureHopkins Center Inaugural Program

NOVEMBER 1962 -

Feature

FeatureDemocracy's Influence on University Education

January 1960 By BERTRAND RUSSELL -

Feature

FeatureDARTMOUTH ALUMNI FUND REPORT

NOVEMBER 1963 By Charles F. Moore, Jr. '25 -

Feature

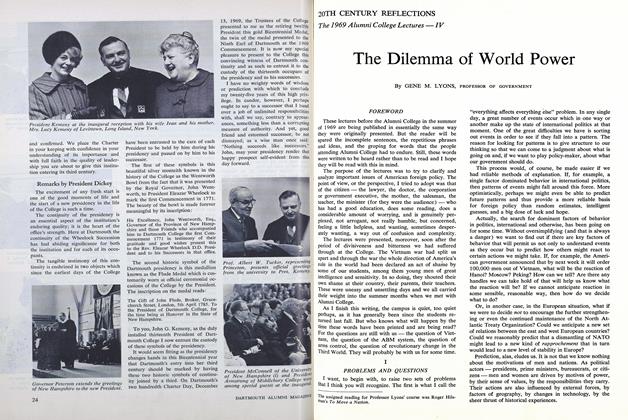

FeatureThe Dilemma of World Power

APRIL 1970 By GENE M. LYONS -

Feature

FeatureGove (gōv), Philip (fĩl'ìp) B.

MAY 1959 By JAMES B. FISHER '54