RIVERMEN no longer dance lightly over logs floating down the Swift and Dead Diamond Rivers into the Magalloway and the Androscoggin, and lumber jacks no longer drive horses or use cross-cut saws in the 42-square-mile forest fastness of northern New Hampshire. But logging is still very much alive, in fact healthier than ever, up in the Second College Grant. Present management policy of the substantial timber resource is not only a financial asset to Dartmouth but a means of actually improving the timberland. A review of the Grant's history, the development of the local timber industry, and a description of the current operation may mollify the skeptic.

A township of 26,800 acres in extreme northern New Hampshire was granted to Dartmouth College in 1807 by the state legislature. The grant was made as a partial reimbursement for the loss in 1791 of the township of Landaff* and as a substitute for the revenues of the quickly liquidated 1789 Clarksville Grant in northern Coos County.

The provisions of the Second College Grant stipulated that "the incomes of said land shall be applied wholly and exclusively to assist the education of the youths who shall be indigent and to alleviate the expenses of members of

families in this State, whose necessitous circumstances will render it impossible for them to defray the expenses of an education at said seminary without such assistance."

The "incomes of said land" were expected to derive primarily from the lease of land for settlement and agriculture. Only a few lots were ever leased and little, if any, profit was realized. College historian Leon Burr Richardson notes with considerable understatement that "the region proved to be too remote to attract any considerable number of settlers." Any settlers attracted would have been hard put to transform the still-rugged wilderness into even a semblance of an agricultural paradise. The only revenues received by the College since have been in the form of timber sales.

Although an 1888 advertisement by Dartmouth for contractors to cut softwoods specified that "as this is to be kept as a perpetual income to the College, great care must be taken in preserving the small growth," management of the resource was, until after World War I, egregiously lax. Small amounts of timber were sold piecemeal to a long series of short-term contractors. The income from the Grant between the years 1826 and 1831 amounted to only $2,000. This figure includes with timber sales the damages received from a legal action against trespassers.

Revenues continued to be small throughout the first half of the 19th century, and in 1835 the Grant was almost sold for $50,000. By 1861 the timber income totaled about $21,000. The interest on this capital was applied to scholarship payments to New Hampshire students.

By 1888 the grant had yielded no revenue for 25 years. In that year a longterm lease was negotiated with a timber contractor, George Van Dyke, "to cut down, take, and carry away from said grant three million feet a year during said twenty years of the spruce, pine and cedar, and so much of the fir and poplar as he sees fit to take. . . ."

This contract yielded a substantial revenue for the first time, $3,750 annually, but it was complicated by the continuous charges of trespass and theft against Van Dyke and the International Paper Company. The dispute culminated in 1900 with a complicated suit against International Paper for $275,000 in damages allegedly resulting from willful trespass. As the result of a compromise settlement in 1905 Dartmouth was awarded $62,500.

Not surprisingly, the Board of Trustees began at this time to be more interested in the management of the Grant. In 1905 Phillip W. Ayres was employed as forester to implement a management policy. Placed as an asset on the College books for the first time, the Grant was valued at $225,000.

Because of an epidemic attack of spruce bud-worm in 1918-1919, the Trustees decided in 1920 that it would be wiser to cut the entire crop, at a price which was the highest the market had ever known, rather than risk losing the whole to disease. That year a contract was made with the Brown Company of Berlin, New Hampshire, to cut for use as pulp all the softwood timber on the tract. (Nature provides in odd ways. Around 1910 the Grant came perilously close to being sold a second time. Justification for keeping it soon fell to the lowly budworms, whose depredations meant a million-dollar bonanza in timber contracts.

The substantial return from this contract was regarded as a reserve fund which could be used over a 40-year period. The idea was that after four decades the pulp wood crop would have renewed itself and a second yield as sizeable as the first would be available. An act passed by the New Hampshire legislature in 1919, permitting the College to use for general purposes the portion of the fund not required for scholarships for indigent New Hampshire students, greatly facilitated, as Richardson observed, "the effective use of this fund."

Robert Monahan '29, College Forester from 1947 to 1970, summarized the nature of the income during this period in a 1948 ALUMNI MAGAZINE article, "Stumps and Scholarships": "During the 1920-1931 decade the net receipts for stumpage sold under this contract amounted to $1,536,889. During the 1920-1935 period the invested income from the Second College Grant Reserve Fund totaled $665,887. In the same period the College expended $884,167 for scholarships and general purposes, leaving in the fund in 1935 a balance of $1,213,970. In addition, $161,558 was used during 1928-29 for land purchases

and for improvement of the College plant." During Monahan's time a series of contractors cut millions of feet of highquality birch and maple, much of it for use in the manufacture of furniture.

In April of 1967 the Trustees suspended cutting operations at the Grant and named an advisory committee to evaluate existing policy. Members were Edward B. Hinman '35, who was at that time president of International Paper Company; Zebulon W. White '36, then associate dean of the Yale School of Forestry; and the late Rand N. Stowell '35, then President of Timberlands, Inc. of Dixfield, Maine. The committee concluded that a detailed forest management plan should be formulated for future timber operations, that arrangements should be made for engaging experienced consulting management, and that Dartmouth's use of the Grant for educational and recreational purposes should be developed and encouraged.

Following this report, the College engaged the Prentiss & Carlisle Company of Bangor, Maine, to do a detailed study of the Grant and to work out a long-term management plan. On the recommendation of Prentiss & Carlisle, Dartmouth contracted with the Seven Islands Land Company of Bangor for the direct management of the timber operations. The contract went into effect in 1970-1971 and runs on a three-year renewable basis.

Seven Islands receives $4,860 annually for their management services which consist of marking the trees, scaling the cut timber, monitoring markets, establishing cutting priorities, and supervising the overall operation. The actual cutting is not done by Seven Islands, but by a local contractor, presently Clarence Gray, based in Errol, New Hampshire.

Gray's outfit cuts in an area designated by Seven Islands according to a slightly revised version of the Prentiss & Carlisle management plan, which divided the Grant into, 11 compartments defined primarily by natural drainage basins. The order in which these sections are cut depends on such factors as existing roads and bridges and the maturity or quality of the stand of timber.

This October Gray had five cutting crews, made up of three men each, in addition to two or three bulldozer and truck drivers doing road construction, working in the Grant near Alder Brook. The trees he cuts are not usually marked, but are selected on the basis of diameter limits measured at chest height. The limit, for example, which varies from location to location, might be seven to eight inches for softwood, ten inches for soft maple, twelve inches for hard maple and spruce, and fourteen inches for birch. Gray is presently cutting with a goal of 4,000 cords per year. A large part of the operation has been the removal of overly mature and poor quality trees left from previous high grading operations. That is, contractors in the past had removed only the best and left the rest, a highly profitable practice on the short term, but wasteful and contrary to sustained yield objectives. The present "clean-up" policy allows for much more vigorous young growth and leaves the woods - which were often previously abused - healthier, sightlier, .and less prone to fire than if they were allowed to grow without any harvesting at all.

Even with the sophistication of the machinery available for use in the Grant, Gray's foreman estimates that 30 per cent of the timber is left in the woods in the form of tops, limbs, and other slash. Seven Islands, however, anticipates the development of markets and technology in the very near future that will make it economically feasible to bring the entire tree out of the woods tops, branches, and all for conversion into chips on the spot. This will make possible a much higher yield per acre, particularly in marginal areas, and leave much less of a visual impact on the woods.

Even now, management and removal methods are a marked improvement over those of the past in terms of long-range productivity, continuous profits at a higher average, and aesthetic and recreational considerations. The roads required in the old days of horse logging, for example, took approximately 17 per cent of the land out of productivity, whereas the trails required for mechanical skidders require only four per cent.

The modern management perspective on the Grant sees the timber as a crop, a renewable resource, which will eventually be harvestable on a 15-year cutting cycle. With,luck, this goal will be achieved by 1990. A recent timber management publication summed up the sustained yield-multiple use philosophy: "... we are embarking upon an era of intensive forest management, with the goal of increasing annual fiber and financial yields per acre. Most importantly, we own a uniquely renewable resource; the cycle of harvest, regeneration, cultivation, and reharvest can be repeated forever, as long as we follow sound practices. This approach in no way conflicts with our commitment to the other economic and social values of the forest. Our lands will continue to benefit the general public as watersheds, game habitats, and recreational areas."

In 1974 Dartmouth grossed $31,000 from stumpage fees. Although by no means overwhelming, this revenue does allow the extensive acreage of the Grant, an impressively large recreational and educational resource, to pay for itself. (From the gross income the College pays almost $5,000 a year in management fees to Seven Islands, provides the salary of the gatekeeper in this remote northern outpost, and maintains certain roads and facilities.) The total gross income for the years 1970-74, received on 19,330 cords of harvested wood, amounted to just over $115,000. This income is substantially higher than estimated due in part to the development of hardwood pulp markets. Net revenues are no longer used as a scholarship fund but as part of Dartmouth's general operating funds.

Gray pays the College a stumpage price set by Seven Islands in relation to existing markets, accounting for the highest possible value of the wood removed. Highest prices are paid by the market for hardwood saw logs, classified into three grades, most of which go to the Kimberley-Clark Company in Sawyerville, Quebec. Pulpwood brings the lowest price on the market.

Gray clears approximately $2.50 per cord, rather a thin margin considering his substantial investment in equipment and the 4,000-cord-per-year limit on volume. He loses money, in fact, on the pulpwood which he is required to bring out, but makes it up on hardwood saw logs. Even the percentage of hardwood will remain low for several years because of the previous high grading.

To many, a logging operation is an eyesore; to some, a sacrilege. The College and the Seven Islands Company have shown themselves to be extremely concerned with minimizing the impact of harvest on the aesthetic and recreational value of the land and more than sensitive to the concerns of Grant visitors.

Certain scenic areas have been preserved from any cutting at all, large deer yarding areas have been designated and protected in cooperation with the New Hampshire Fish and Game Department, no cutting is permitted within 300 feet of roads and streams, and certain old loading yards near roads or streams are being reseeded. The current logging roads safeguard previously inaccessible portions of the Grant against uncontrollable fire.

The timber stand at the Grant, historically a financial resource, promises to be an increasingly profitable investment, both in terms of dollar income from stumpage sales and in terms of improving forest value. The multiple recreational and educational uses of the Grant will continue to exist without conflict. Although the correlation is no longer directly between "stumps and scholarships," the timber being cut on the Grant continues to make an important contribution to Dartmouth and to the Grant itself.

Tall Timber

IN ten minutes, with deft use of his chain saw, Alan Peart notches, fells, and limbs (right) a hard maple measuring more than three feet across at the stump. Rotting on the inside, the tree is a leftover from previous high grading operations, but it still will produce some valuable timber for the logging contractor. Peart himself is paid by the wood he cuts — between $21-23 per man for each thousand feet brought out by a three-man crew.

After Peart tops and limbs the maple, it is dragged out of the woods by skidder (opposite, top) to a staging area where another team cuts it into saw logs. The last river drive in the region took place in 1963. Now the timber is hoisted aboard an 18-wheel truck and hauled to Quebec. From woods to highway can take less than a day and, although the romance is missing, the forest is probably left in better shape than during the cut-and-run, laissez faire time of 75 years ago.

Men and Machines

CLARENCE Gray (above), logging contractor at the Grant, looks tough, and he undoubtedly is. His investment in men and machines is substantial. There are 15 to 20 men on the job, including brothers Clement and Fernand Lacasse (below, left), who work together on a cutting team. Resembling an angry forest insect, a skidder (right) costs between $21,000-38,000 and has a maximum life of five years. Gray has five skidders in use at the Grant, plus trucks, a crane, and several bulldozers. His father once logged the same area, and his son Joe, shown below with Nick - reputedly a Bunyanesque cross between a bear and a Newfoundland - is now a foreman at the Grant.

*Controversy over ownership of the town of Landaff, granted to Eleazar Wheelock in 1770, was a constant source of litigation and even the occasion for rioting between the years 1779 and 1791. Prior recipients of the granted town had forfeited possession, by declaration of the Governor and Council, because of their failure to carry out the terms of settlement. The original owners, however, won the land back in a court action, a considerable financial blow to the College.

Sidney Turner is a scaler for the SevenIslands Company. His grandmother,Grace Turner, was gatekeeper at the Grantfor many years.

Skidders are not only costly but sometimes temperamental.Alfred Belanger, one of two full-time Gray mechanics, peers in ata faulty wheel gear, and a few moments later registers his feelingon the subject with a Gallic flourish. The skidder shown at thebottom of the page was mired to the cab in mud and had to bewinched out.

Dan Nelson '75, one of the Magazine's undergraduate editors this year, is a frequentvisitor to the College Grant.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureOBESITY

November 1975 By MARy BISHOP ROSS -

Feature

FeatureFairly Faced

November 1975 By WILLIAM W. COOK -

Feature

FeatureSome Faults, Some Solid Achievements

November 1975 By M.B.R. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

November 1975 By WALTER C. DODGE, THEODORE R. MINER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1942

November 1975 By RICHARD W. LIPPMAN, A. JAMES O'MARA -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

November 1975 By DOUGLAS WISE, BARRY R. BLAKE

DAN NELSON

-

Feature

FeatureHigh On Your Dial

December 1975 By DAN NELSON -

Feature

FeatureES 21

January 1977 By DAN NELSON -

Feature

FeatureSee How They Run

NOV. 1977 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureThe Trustees: 15 men and a woman with ultimate authority

October 1979 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureConjuring Ethics in the Curriculum at Dartmouth

March 1981 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureMen and Women: What's the Difference?

OCT. 1977 By Dan Nelson, Shelby Grantham

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Cold, Cold World of CRREL

FEBRUARY 1964 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

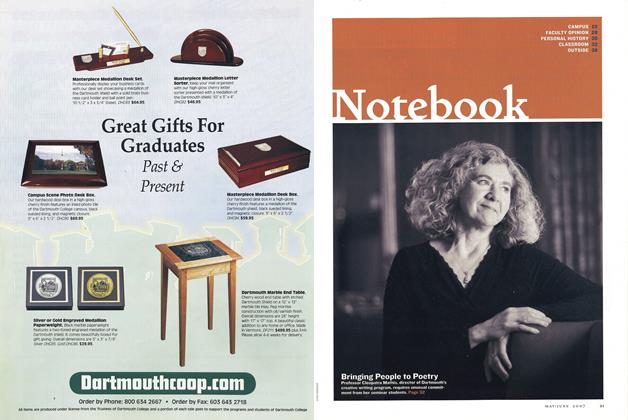

FeatureNotebook

May/June 2007 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

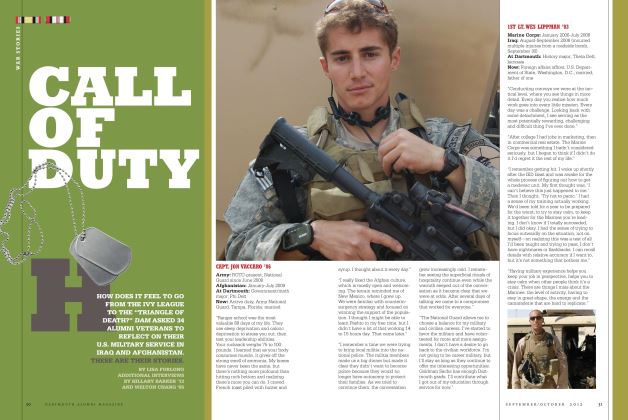

FeatureCall of Duty

Sep - Oct By LISA FURLONG -

Cover Story

Cover StoryTeacher in the Dorm Room

MARCH 1989 By Paul Susca '80 -

Feature

FeatureThe New England Review and Bread Loaf Quarterly

NOVEMBER 1986 By Peter Mandel -

Cover Story

Cover StoryWhat’s Next

MAY | JUNE 2018 By TIFFANIE WEN