DAVID D. Whipple '46, until last spring political-military officer at the U. S. Embassy in Cambodia, was in Hanover for his June reunion, bringing a first-hand account of the final days before the American withdrawal from Phnom Penh.

A career diplomat with a talent for turning up in global hotspots, Whipple was aboard the last flight of helicopters to leave. He had been at the Phnom Penh post for only a year, but his Indo-China experience dates back to his first assignments - he was fresh out of graduate school - to Hanoi, then Saigon in 1951 and '52 before the French were driven out. Subsequent tours of duty have been in Burma and Thailand, as well as the Congo during its most turbulent days of the '60s.

The orderly withdrawal from Phnom Penh stands in extraordinary contrast with the panic that accompanied the American pullout from South Vietnam, just as the chaos that followed in Phnom Penh differs strikingly from the unexpected tranquillity of the Viet Cong's takeover of Saigon.

During the last few days in Phnom Penh, Whipple reported, American personnel roamed the city at will, endangered only by Khmer Rouge rockets falling on the city. Unlike the South Vietnamese, Cambodian civilians - "utterly, completely dependent on us" - displayed no animosity, government troops aided in the evacuation, and "little children waved at us as we left" from an open field behind the Embassy. Until almost the end, "they didn't believe that we wouldn't continue support," Whipple said. "It was heart-breaking."

It was U. S. policy to take out all embassy employees and their families and anyone else who wanted to go, and evacuees had been leaving for some time on the return flights of American planes ferrying food and military supplied into the capital. Space had been saved on the final flights for some who elected to stay and apparently paid with their lives. The State Department had anticipated a blood bath, Whipple said, but not to the extent it apparently occurred.

The word "apparently" recurred over and over in his account because of the tight lid clamped on the country following the American evacuation. Even those countries which had recognized the Khmer Rouge government immediately were not permitted to send in representatives, and it has been only recently that word has been coming out of the total reordering of Cambodian society. At that time the State Department denied any knowledge of which faction of the strange coalition - some leaning toward Hanoi, some toward China, some fiercely independent nationalists - would win, or had won, the power struggle.

Whipple contends that government forces had a good chance of beating back the Khmer Rouge had American aid been continued until the rainy season swelled the Mekong River, making it once again a safe supply route far cheaper than the airlift. As funds dwindled, fewer planes came in; food took priority over war material, making the surrender inevitable.

As to the future U. S. role in Southeast Asia, Whipple said only: "The ability we've had in the past to influence events is vastly curtailed.

"The dominoes are falling, aren't they?"

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureBefore the Revolution

October 1975 By ALBERT F. MONCURE JR., RONALD V. NEALE -

Feature

FeatureA Dialogue for Autumn

October 1975 By COREY FORD -

Feature

FeatureQuartet in Residence

October 1975 By DAVID WYKES -

Feature

FeatureA MEMORANDUM

October 1975 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Article

ArticleThe College

October 1975 -

Article

ArticleThe Trolley Never Stopped Here

October 1975 By GEORGE W. HILTON

M.B.R.

-

Article

ArticleOil Man Caracas

November 1974 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleThe obscure little pin-prick circled above recently sent out x-rays more intense than any before recorded. But what is this "unusual thing" in the sky?

October 1975 By M.B.R. -

Article

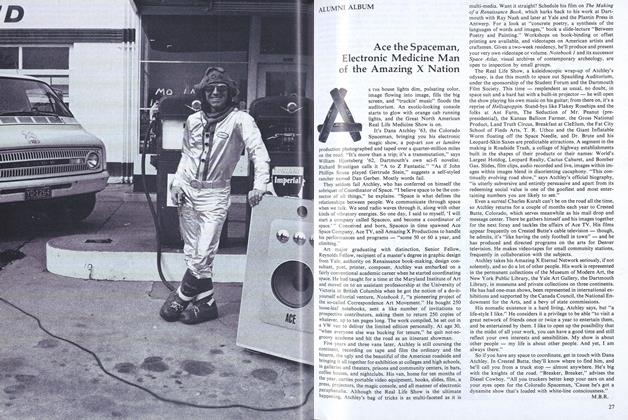

ArticleAce the Spaceman, Electronic Medicine Man of the Amazing X Nation

April 1977 By M.B.R. -

Article

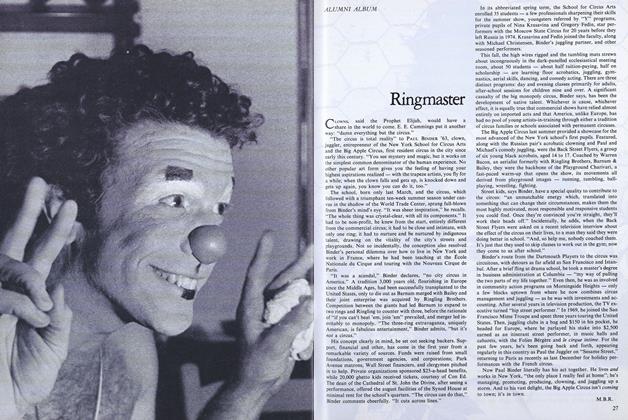

ArticleRingmaster

DEC. 1977 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleSire of the Sitcom

October 1978 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticlePolicy Manager

November 1980 By M.B.R.

Article

-

Article

ArticleMasthead

November, 1912 -

Article

ArticleWORK PROGRESSING ON NEW EDITION OF GENERAL CATALOGUE

January, 1925 -

Article

ArticleBOSTON GLOBE EXPLAINS DARTMOUTH'S GROWTH

March 1925 -

Article

ArticleMoosilauke Ski Race

APRIL 1930 -

Article

ArticleJUST before Christmas, 1973,

June 1974 By P.K.N. -

Article

ArticleCarnival Pictorial

APRIL 1929 By Robert T. Drake

M.B.R.

-

Article

ArticleOil Man Caracas

November 1974 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleThe obscure little pin-prick circled above recently sent out x-rays more intense than any before recorded. But what is this "unusual thing" in the sky?

October 1975 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleAce the Spaceman, Electronic Medicine Man of the Amazing X Nation

April 1977 By M.B.R.