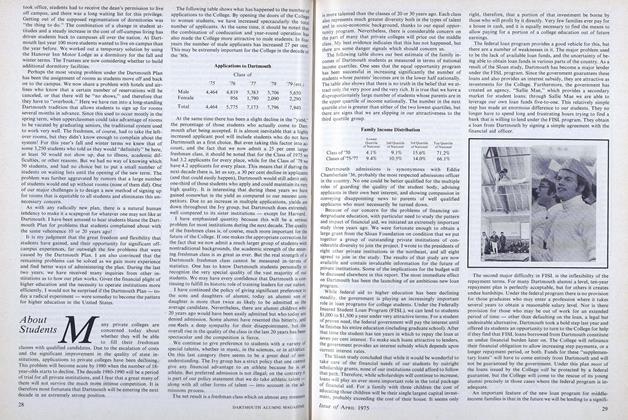

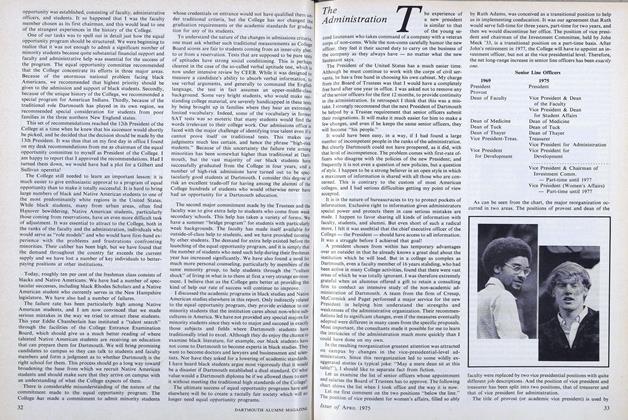

Having been a member of the Dartmouth faculty for 16 years before taking office as President, I had very strong feelings about the role that should be played by the faculty in academic decision-making. My first act as President was to appoint a Presidential Commission on the Organization of the Faculty (PCOF) for the purpose of proposing a more streamlined organization and to offer the faculty a more significant role in decision-making. The new President had a great deal to learn; he had to learn that people can at the same time demand more power and refuse it when it is offered to them.

The PCOF was broadly representative of the various faculties and, with the participation of senior administrators, worked hard and productively under the chairmanship of Professor John Copenhaver '46. The committee recommended a series of changes, which although they contained important ideas, proved to be too sweeping to gain faculty acceptance. Nevertheless, they would eventually have an important impact on the reorganization of a portion of the faculty decision-making structure.

Dartmouth College is organized into four separate faculties: the Faculty of Arts and Sciences and the faculties of the three professional schools. (This is made even more complicated by the fact that the members of the Thayer School faculty are also members of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences.) While there did exist a paper organization called the General Faculty of Dartmouth College, it had no power other than to listen to the annual report of the President of the College. Perhaps the most significant outcome of the PCOF recommendations was a new charter for the General Faculty. The major obstacle was a fear on the part of members of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences that the professional schools might outvote them on important issues. This fear existed even though the Faculty of Arts and Sciences outnumbers the three other faculties combined. Various attempts to limit the voting power of the professional schools by artificial means failed.

Finally, a very sensible compromise was worked out: all members of all faculties can vote in meetings of the General Faculty, although the vote is not binding on the four separate faculties. I hope that one day the individual faculties will grant more power to the General Faculty, but it was an important step forward to provide a forum where issues could be debated jointly by the four faculties. Equally important was the establishment of a steering committee which can take limited actions on behalf of the various faculties and can assure that the agenda for meetings of the General Faculty are well structured. The establishment of the College-wide Council on Budgets and Priorities, described below, would have been impossible without a steering committee that prepared a carefully thought-out plan for consideration by the General Faculty.

In addition to committees of the individual faculties, there are a number of councils of the General Faculty. Councils deal with graduate studies, libraries, the computer, sponsored activities, and honorary degrees. Technically, these councils had in the past reported to the General Faculty, but since the latter could not vote on anything, it couldn't even take the pro forma action of accepting the annual reports. The steering committee has begun to play the important role of reviewing reports of councils and monitoring their effectiveness.

The most sweeping recommendation of PCOF was to establish a community council, with broad representation, to deal with a wide range of College problems. While the proposal was ex- tremely imaginative and very carefully worked out, it failed to gain faculty support. It may have been too radical a change to gain acceptance, but it was legitimately criticized for imposing too great a burden on too many participants. While the overall council has not been established, two of the functions that it was designed to carry out have been implemented through special committees.

The first of these is an advisory committee on investment ob- jectives. This committee advises the Board of Trustees on issues concerning its investments, other than monetary returns. It is charged with considering social implications of investment policies and plays an important role in advising the Board on the voting of proxies. While its role is purely advisory, in its second year of existence all the committee's recommendations were accepted by the Board.

The second such broadly representative committee is the Council on Budgets and Priorities. In happier days one could fund all projects that were clearly desirable for the future of the College. In a period of fiscal tightness, some difficult choices have to be made. I consider it very important to legitimize such choices by having a broadly representative group that can make an independent assessment of priorities and serve as a watchdog to see that the College's budget is designed to carry out our priorities. This body has been established as a standing council of the General Faculty, upon the initiative of the steering committee. The procedure through which this council was established gives me great hope for the future of the General Faculty. The main debate occurred during a meeting of the General Faculty, which led to a number of amendments in the proposed constitution. Once this debate was over, all four of the separate faculties endorsed the action.

The Council on Budgets and Priorities has representation from all four faculties, as well as key administrative officers, students an alumnus, and a member of the staff of the College. It is chaired in its initial year by Dean Hennessey, who represents Tuck School.

This council serves as a good illustration of my views of the proper governance of the institution. Constructing the annual budget is the single most important means through which the President and his senior officers can shape institutional priorities. And having the final right to modify this budget is one power that the Board of Trustees must never delegate. In spite of these strong convictions, I firmly believe in the necessity of having a broadly representative council on budgets and priorities.

The age has long passed in which college presidents, or boards of trustees, could arbitrarily set budgets and tell the various constituencies to "accept our decisions because we know best. At a time when we cannot meet all legitimate needs and everyone is asked to make sacrifices, it is extremely important that there be a representative forum which can make an independent judgment on the fairness and wisdom of our decisions. The Council on Budgets and Priorities is purely advisory in nature, thus protecting the ultimate authority of the President and Board of Trustees. But this does not mean that the council is powerless. It has the power to examine all aspects of the budgeting process, other than individual salaries. This gives a new openness to decisions on priorities - decisions made entirely in closed administrative sessions invariably create suspicion even if the decisions are good ones. The council has a guarantee that its recommendations will be heard by the President and by the Board. We are not obligated to accept these recommendations, and I expect that I will from time to time disagree, but in many cases they will have a decisive influence.

Finally, the council must report to the General Faculty. If the council feels that we have done well in the budgeting process, its support will be invaluable in gaining wide acceptance. If, on the other hand, it feels that there is something significantly wrong in the process of setting priorities for the institution, the council has a broad public forum in which to bring this to light. While it is clearly impossible to turn all members of the faculty, the student body, the alumni, and the employees of the College into experts on the Dartmouth budget, I hope that it will give them considerably more confidence to know that a group representing all these constituencies has spent many long days examining the process and has had a significant input into the decisions.

A final area in which the commission on the organization of the faculty had an important impact is streamlining the decision-making procedures of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences. Recommendations were approved to make the executive committee of the faculty smaller, better organized, and directly representative of the departments of the College. The functions of the divisional councils of the faculty were spelled out more clearly, as were the roles of the dean of the faculty and the various associate deans. A procedure has also been adopted under which the performance of deans is reviewed once every four years. Perhaps these changes are not quite as spectacular as those the commission had hoped for, but they have made the decision-making process easier and more effective.

A recent example of the complexity of institutional decision-making is the ROTC debate. The Trustees requested in the fall of 1973 that this issue be reexamined. A broadly representative committee, under the able leadership of Professor Gene Lyons, examined all the possible alternatives, and presented the pros and cons of each. They reached a consensus on most issues but split on the desirability of an on-campus program. Since that time we had an Alumni Council resolution favoring an on-campus program somewhat similar to that now in existence at Princeton, and a vote of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences opposing such a program. Next we must explore with the Department of Defense just what options might be open to the College. When all the information is in, the Trustees must make a decision that clearly cannot please all constituencies. While honest disagreements are part of academic life, it is a matter of great satisfaction to me that an issue that once raised violent tempers can now be discussed calmly and rationally.

Another important development in giving the faculty a more significant voice has been closer contact with the Trustees. The first important change was the addition of faculty members to the Board's committee on educational affairs and facilities. The chairmen of three committees of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences and the three professional school deans participate in the deliberations of this Trustee committee, although voting is reserved to Trustee members. All of us who have watched this experiment during the past two years feel that it has been an important step forward. Plans have now been made for the Council on Budgets and Priorities to have a similar input into the budget committee of the Board. In addition, at the request of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, the Trustees have informal meetings with groups of faculty members.

An important development during the past five years has been student representation on a number of departmental and general faculty committees. For example, there is student representation on the committee on educational planning, which makes longrange proposals on the undergraduate curriculum. However, selecting students for these bodies can be frustrating. In the late '6os students began to demand "more power" and at the same time voted out student government. This has made it more difficult to legitimize the selection of student representatives. One common procedure is to invite students to apply for membership on a given committee and then have the rest of the members of the committee choose students on the basis of their applications.

While I believe that the decision-making structure at Dartmouth is good, it does have its weaknesses. We have too many committees and too many man-hours are spent in committee meetings. As in any other representative form of government, it is common for one committee to second-guess another committee, mittee,or even for a committee to reverse the recommendations of the same committee from the previous year. These are perhaps unavoidable problems in a democracy. What I find more frustrating is the reluctance of the faculty to police itself in certain key areas. A single example may illustrate this shortcoming.

The Faculty of Arts and Sciences became quite concerned about the inflation of grades at Dartmouth and an inconsistency in the awarding of grades. After two years of debate a new grading system was adopted which provided for a larger number of grades (including pluses and minuses). This may or may not have been a step forward, but it had absolutely nothing to do with the problem of grade inflation. Both the inflation of grades and the inconsistency of grading have continued under the new system. It is clearly the faculty's prerogative to set the standards for grading. What is frustrating is that the vast majority of faculty members recognize certain practices (e.g. giving all A's and B s in a very large course) as a violation of their own policies, but the faculty as a whole nevertheless refuses to police its individual members. Yet if we are going to save the meaningfulness and credibility of Dartmouth grades, we must find a solution to this problem.

Features

-

Feature

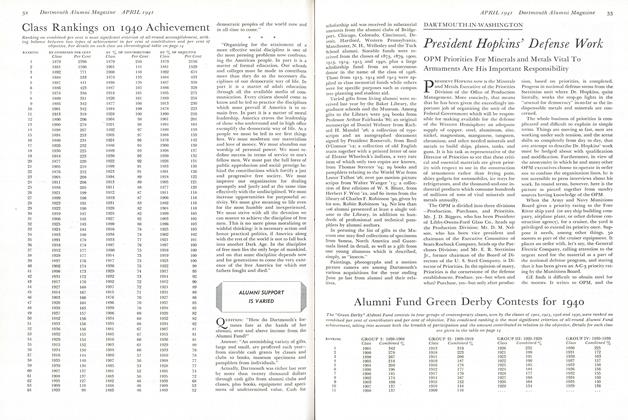

FeatureAlumni Fund Green Derby Contests for 1940

April 1941 -

Feature

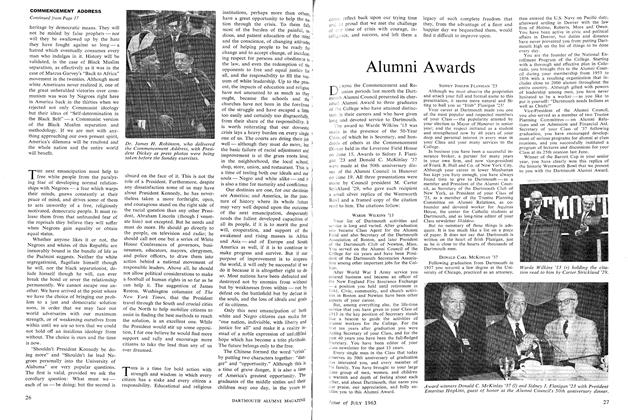

FeatureThe Alumni Council's 50th Year

JULY 1963 -

Feature

FeatureThe Philosophy of Culture

DECEMBER 1966 By ALBERT WILLIAM LEVI '32 -

Feature

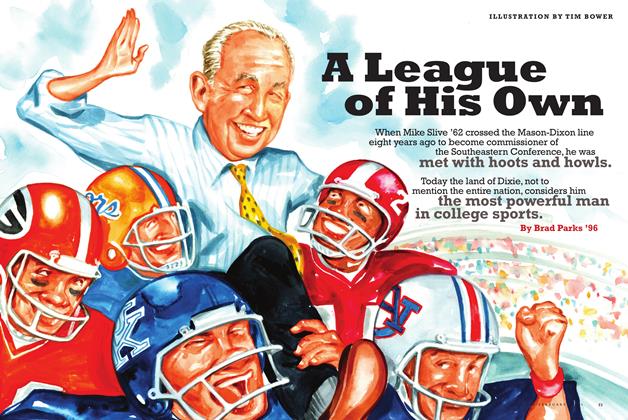

FeatureA League of His Own

Jan/Feb 2011 By Brad Parks ’96 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Global Classroom

Sept/Oct 2004 By CHRISTOPHER S. WREN ’57 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryStimulating Poison

MARCH 1995 By George Hoke '35