Notes on a realist among the Cassandras and one microcosmic answer to a macrocosmic question

NOV. 1977 R.H.R.Notes on a realist among the Cassandras and one microcosmic answer to a macrocosmic question R.H.R. NOV. 1977

CAN THE world be fed in the year 2025? Probably not, say many scientists agronomists, demographers, geographers, climatologists - and the evidence they adduce posits a series of complex, interrelated events which taken together portend nothing less than human disaster. First, they point out, the world's population will in all likelihood double by 2025. Second, climatic variability will increase on a world-wide, long-term scale. Specifically, large areas of the globe are cooling, and even a small drop in the annual average temperature will render millions of acres of presently cultivated agricultural land useless. Third, as the present energy shortage becomes more acute our energy-intensive food production methods will become increasingly unworkable because of sky-rocketing prices of the irrigation water and the fertilizers upon which such mass-production methods depend. Finally, large tracts of arable land will continue to be converted to urban or suburban uses. Even today in the United States alone, something on the order of 65,000 agricultural acres per month are thus lost to food production.

No wonder the pessimism then. Clearly, the poet's prediction for our century was apt: things fall apart; the center cannot hold. Fortunately, not everyone agrees. Robert E. Huke '48, professor of geography, is one of the unbelievers. Can the world be fed in 2025? Maybe - just maybe - yes, Huke answers. And along with a co-author, Robert Sherwin Jr. '67, he has recently written a small book which suggests one, limited, specific avenue of approach to the universal problem: A Fish and VegetableGrower for All Seasons (Norwich Publications, Box F, Norwich, Vermont, 125 pp. $4.95).

A modest enough book, it deals with the macrocosmic question from a decidedly microcosmic position. For it tells the reader how to build, of all things, his own food-producing greenhouse. But Huke is the kind of scientist who passes easily and naturally from the general to the specific; solutions to the food problem are urgent, he argues, and if you are going to get practical about them you must, after all, start someplace.

Huke's starting place was his own backyard in Norwich, where three years ago his scientific theories, his years of training and experience in geography and agronomy, and his practical imagination all came to focus in a round, 17½ foot-diameter geodesic dome erected on a framework of pine struts and covered with PVC plastic and fiberglass sheeting. Ordinary materials, to be sure, but a far from ordinary structure. For the Huke dome is a unique concept, an entirely self-contained, balanced food-producing unit which, with its own windpowered generator, relies only minimally if at all on extraneous power sources.

Huke's motives in building the greenhouse in the first place, he concedes, were less those of the theoretical scientist than those of the practical backyard gardener bedeviled by the short Vermont growing season. "My tomatoes simply froze too early to suit me," he says. The answer? Obviously, a greenhouse. But a greenhouse requires energy - even more important, a means for storing energy - and the price of energy in the Upper Valley is as prohibitively high as the growing season is short. How then to store natural energy during the warm months and gradually release it during the cold? The answer occurred to Huke as the result of some work he had previously done at a University of Arizona experiment station in intensive agriculture; it was water. Approximately one-third of the area of the greenhouse, Huke reasoned, should contain water, which, because it both cools and warms more slowly than air, has a moderating effect on the environment. And thus it went. Water suggested aquaculture, which in turn suggested fish, a primary and efficient producer of protein. Step by step the basic idea which makes the Huke dome unique was created: the combination of fish production with vegetable growing in a self-contained, mutually reinforcing controlled environment.

The Norwich model of the dome has operated efficiently for three years. In his three-foot-deep pond inside the dome Huke grows talapia during the summer, trout during the winter, and he harvests both. The water in the pond not only creates favorable temperature and humidity conditions for growing vegetables but also, along with the fish effluent, fertilizes and waters the vegetables as well. Perhaps most significant, the dome has moderated the harsh extremes of even Upper Valley temperatures and has extended the growing season from an average 123 days to an astonishing 300 days per year.

Can the concept of the Huke dome - more accurately, thousands of such domes, expanded, immensely enlarged, made more efficient - significantly contribute to" feeding eight billion people by 2025? Huke's answer is realistic. The dome is certainly not a panacea, he quickly points out; it is probably not even universally applicable. It makes only a small dent in an enormous problem. Properly used, however, this new concept which combines intensive aqua-and agriculture can play some part in producing future food supplies.

What Huke hopes for, as he writes in his book, is "the rapid expansion of controlled environment enclosures ... at the urban fringe, in the suburbs, and in rural non-farm areas. In some locations these would be large structures to provide vegetables and fish for 100 or more families. In the suburbs and more rural areas the structures will be designed to provide part of the needs for a single family. . . . The soil will be fertilized with sludge from the local sewage plant and watered with the waste-enriched effluent from the fish tank filter. . . . Solar energy will provide the major non-human input and the semi-enclosed system will allow for the exclusion of major atmospheric pollutants. The micro-world of the dome farm and the individual contact with living systems will help to overcome the psychological rigors of a crowded world and will help in a small way to provide an improved diet."

No one, least of all Huke, claims that the dome is "the solution" to the food problem. Indeed, Huke is a scientist, with a scientist's respect for facts, and the total answer - if answer there is - will come, he believes, from no single dramatic breakthrough but from the work of many scientists and social scientists approaching the problem from different points of view. "I like multiple solutions," he says. "The push has to be on many fronts simultaneously."

Meanwhile, there is that small geodesic dome in the backyard in Norwich. But meanwhile, too, Huke is launched on yet a newer project: a' plan to utilize the warm water discharged from the Vermont Yankee nuclear power plant at Vernon for a gigantic fish-farming system.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureFie on the Flush Toilet

November | December 1977 By Harold H. Leich -

Feature

FeatureSee How They Run

November | December 1977 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

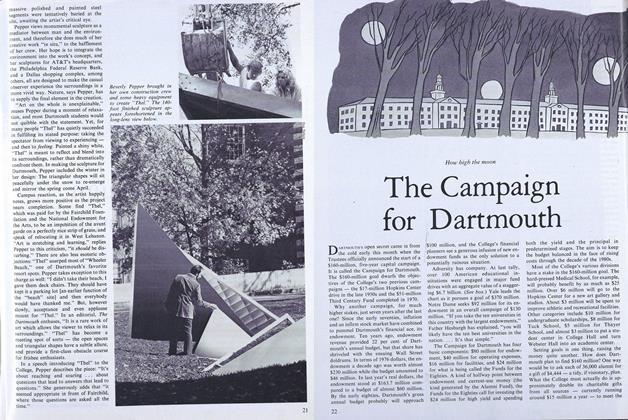

FeatureThe Campaign for Dartmouth

November | December 1977 -

Article

ArticleThe DCMB Double-entendre March

November | December 1977 By Anne Bagamery -

Article

ArticleDick's House Is Her House

November | December 1977 By S.G. -

Article

ArticleTheir Fathers' Sons

November | December 1977

R.H.R.

-

Article

ArticleFurther Mention

May 1976 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksNotes on a humanizing craft, a National Book Award, the Adamses, Avant-garde dancers, Irving Howe's tribute, and the Texas nation.

June 1976 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksCity Views

April 1977 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksNotes on a Pulitzer not given and on Dr. Bob, a gruff, humane Yankee who helped found AA

JUNE 1977 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksNotes on a Yale man's journal and the 'elbowing self-conceit of youth.'

MARCH 1978 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksOut of the Night

November 1978 By R.H.R.

Books

-

Books

BooksFaculty Articles

JANUARY 1965 -

Books

BooksBOSTON POSTAL MARKINGS TO

January 1950 By C. N. Allen '24 -

Books

BooksMISSION IN TORMENT: AN INTIMATE ACCOUNT OF THE U.S. ROLE IN VIETNAM.

JULY 1965 By ERNEST P. YOUNG -

Books

BooksPREMIER MANUEL. GRAMMAIRE ET CIVILISATION FRANCAISES.

November 1954 By FRANCOIS DENOEU -

Books

BooksTHE STORY OF AMERICAN DISSENT.

November 1934 By Malcolm Keir -

Books

BooksTALL TREES, TOUGH MEN.

MAY 1967 By ROBERT S. MONAHAN '29