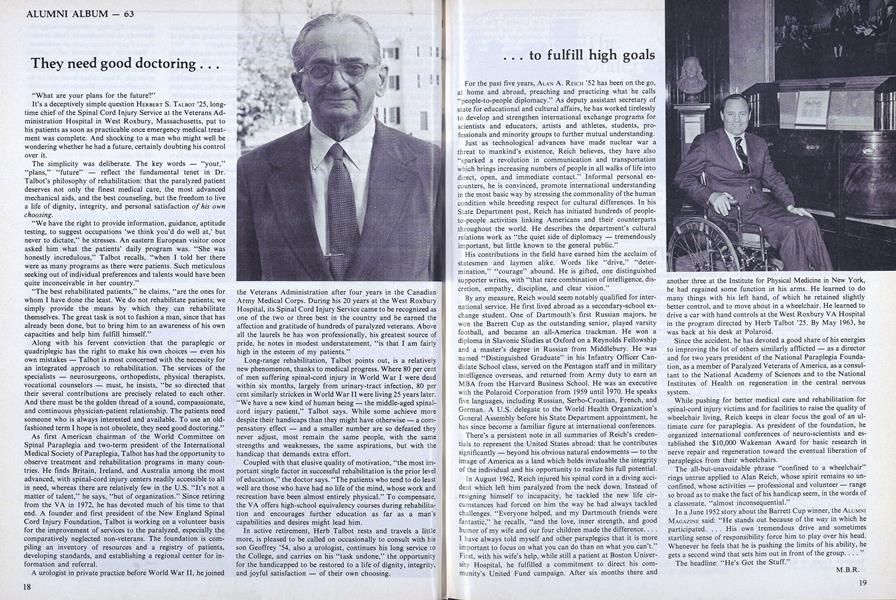

For the past five years, ALAN A. REICH '52 has been on the go, at home and abroad, preaching and practicing what he calls "people-to-people diplomacy." As deputy assistant secretary of state for educational and cultural affairs, he has worked tirelessly to develop and strengthen international exchange programs for scientists and educators, artists and athletes, students, professionals and minority groups to further mutual understanding.

Just as technological advances have made nuclear war a threat to mankind's existence, Reich believes, they have also "sparked a revolution in communication and transportation which brings increasing numbers of people in all walks of life into direct, open, and immediate contact." Informal personal encounters, he is convinced, promote international understanding in the most basic way by stressing the commonality of the human condition while breeding respect for cultural differences. In his State Department post, Reich has initiated hundreds of people- to-people activities linking Americans and their counterparts throughout the world. He describes the department's cultural relations work as "the quiet side of diplomacy — tremendously important, but little known to the general public."

His contributions in the field have earned him the acclaim of statesmen and laymen alike. Words like "drive," "deter determination," "courage" abound. He is gifted, one distinguished supporter writes, with "that rare combination of intelligence, discretion, empathy, discipline, and clear vision."

By any measure, Reich would seem notably qualified for international service. He first lived abroad as a secondary-school exchange student. One of Dartmouth's first Russian majors, he won the Barrett Cup as the outstanding senior, played varsity football, and became an all-America trackman. He won a diploma in Slavonic Studies-at Oxford on a Reynolds Fellowship and a master's degree in Russian from Middlebury. He was named "Distinguished Graduate" in his Infantry Officer Candidate School class, served on the Pentagon staff and in military intelligence overseas, and returned from Army duty to earn an MBA from the Harvard Business School. He was an executive with the Polaroid Corporation from 1959 until 1970. He speaks five languages, including Russian, Serbo-Croatian, French,'and German. A U.S. delegate to the World Health Organization's General Assembly before his State Department appointment, he has since become a familiar figure at international conferences.

There's a persistent note in all summaries of Reich's credentials to represent the United States abroad: that he contributes significantly — beyond his obvious natural endowments — to the image of America as a land which holds invaluable the integrity of the individual and his opportunity to realize his full potential.

In August 1962, Reich injured his spinal cord in a diving accident which left him paralyzed from the neck down. Instead of resigning himself to incapacity, he tackled the new life circumstances had forced on him the way he had always tackled challenges. "Everyone helped, and my Dartmouth friends were fantastic," he recalls, "and the love, inner strength, and good humor of my wife and our four children made the difference.... I have always told myself and other paraplegics that it is more important to focus on what you can do than on what you can't." First, with his wife's help, while still a patient at Boston University Hospital, he fulfilled a commitment to direct his community's United Fund campaign. After six months there and another three at the Institute for Physical Medicine in New York, he had regained some function in his arms. He learned to do many things with his left hand, of which he retained slightly better control, and to move about in a wheelchair. He learned to drive a car with hand controls at the West Roxbury VA Hospital in the program directed by Herb Talbot '25. By May 1963, he was back at his desk at Polaroid.

Since the accident, he has devoted a good share of his energies to improving the lot of others similarly afflicted - as a director and for two years president of the National Paraplegia Foundation, as a member of Paralyzed Veterans of America, as a consultant to the National Academy of Sciences and to the National Institutes of Health on regeneration in the central nervous system.

While pushing for better medical care and rehabilitation for spinal-cord injury victims and for facilities to raise the quality of wheelchair living, Reich keeps in clear focus the goal of an ultimate cure for paraplegia. As president of the foundation, he organized international conferences of neuro-scientists and established the $10,000 Wakeman Award for basic research in nerve repair and regeneration toward the eventual liberation of paraplegics from their wheelchairs.

The all-but-unavoidable phrase "confined to a wheelchair" rings untrue applied to Alan Reich, whose spirit remains so unconfined, whose activities - professional and volunteer - range so broad as to make the fact of his handicap seem, in the words of a classmate, "almost inconsequential."

In a June 1952 story about the Barrett Cup winner, the ALUMNI MAGAZINE said: "He stands out because of the way in which he participated.... His own tremendous drive and sometimes startling sense of responsibility force him to play over his head. Whenever he feels that he is pushing the limits of his ability, he gets a second wind that sets him out in front of the group...."

The headline: "He's Got the Stuff."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureOur Way in the World: A Conversation with John Dickey

January 1976 -

Feature

FeatureNervi's Concrete Aesthetic

January 1976 By JOHN JACOBUS -

Feature

FeatureA Season on the Racetrack Special

January 1976 By DAVID DUNBAR -

Feature

FeatureFarewell Dear (BOOZY, BRAWLING) Davis

January 1976 By ROBERT SULLIVAN -

Article

ArticleA Reasonable Balance?

January 1976 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

January 1976 By DOUGLAS WISE, BARRY R. BLAKE

M.B.R.

-

Article

ArticleConservator by Design

February 1975 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleOf Ancient Mariners... and Monsters of the Deep

September 1975 By M.B.R. -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth Radical Union

December 1975 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleJazz Man

December 1975 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleMotown Brass, New Model

November 1976 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleSire of the Sitcom

October 1978 By M.B.R.

Article

-

Article

ArticleClass Elections

APRIL 1928 -

Article

ArticleE. W. Knight, '87 Nominated

DECEMBER 1929 -

Article

ArticleNew Bulletin Series

December 1935 -

Article

ArticleWoodhouse-isms

SEPTEMBER 1983 -

Article

ArticleBREAKING THE GALILEAN SPELL

May/June 2009 By Stuart Kauffman -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

August 1942 By Walter Powers Jr. '43