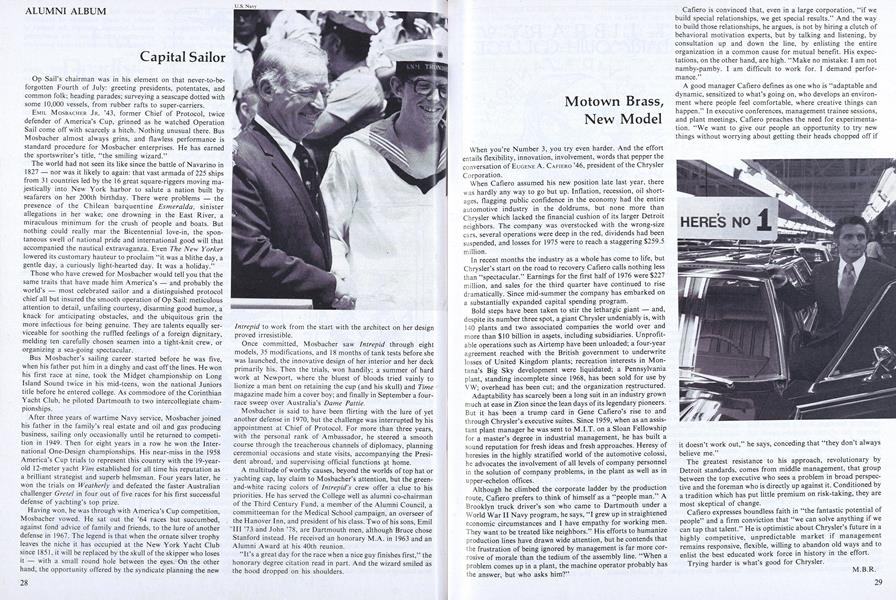

When you're Number 3, you try even harder. And the effort entails flexibility, innovation, involvement, words that pepper the conversation of EUGENE A. CAFIERO '46, president of the Chrysler Corporation.

When Cafiero assumed his new position late last year, there was hardly any way to go but up. Inflation, recession, oil shortages, flagging public confidence in the economy had the entire automotive industry in the doldrums, but none more than Chrysler which lacked the financial cushion of its larger Detroit neighbors. The company was overstocked with the wrong-size cars, several operations were deep in the red, dividends had been suspended, and losses for 1975 were to reach a staggering $259.5 million.

In recent months the industry as a whole has come to life, but Chrysler's start on the road to recovery Cafiero calls nothing less than "spectacular." Earnings for the first half of 1976 were $227 million, and sales for the third quarter have continued to rise dramatically. Since mid-summer the company has embarked on a substantially expanded capital spending program.

Bold steps have been taken to stir the lethargic giant - and, despite its number three spot, a giant Chrysler undeniably is, with 140 plants and two associated companies the world over and more than $l0 billion in assets, including subsidiaries. Unprofitable operations such as Airtemp have been unloaded; a four-year agreement reached with the British government to underwrite losses of United Kingdom plants; recreation interests in Mon-Big Sky development were liquidated; a Pennsylvania plant, standing incomplete since 1968, has been sold for use by VW; overhead has been cut; and the organization restructured.

Adaptability has scarcely been a long suit in an industry grown much at ease in Zion since the lean days of its legendary pioneers. But it has been a trump card in Gene Cafiero's rise to and through Chrysler's executive suites. Since 1959, when as an assistant plant manager he was sent to M.I.T. on a Sloan Fellowship for a master's degree in industrial management, he has built a sound reputation for fresh ideas and fresh approaches. Heresy of heresies in the highly stratified world of the automotive colossi, he advocates the involvement of all levels of company personnel in the solution of company problems, in the plant as well as in upper-echelon offices.

Although he climbed the corporate ladder by the production route, Cafiero prefers to think of himself as a "people man. A Brooklyn truck driver's son who came to Dartmouth under a World War II Navy program, he says, "I grew up in straightened economic circumstances and I have empathy for working men. They want to be treated like neighbors." His efforts to humanize production lines have drawn wide attention, but he contends that the frustration of being ignored by management is far more corrosive of morale than the tedium of the assembly line. "When a problem comes up in a plant, the machine operator probably has the answer, but who asks him?"

Cafiero is convinced that, even in a large corporation, "if we build special relationships, we get special results." And the way to build those relationships, he argues, is not by hiring a clutch of behavioral motivation experts, but by talking and listening, by consultation up and down the line, by enlisting the entire organization in a common cause for mutual benefit. His expectations, on the other hand, are high. "Make no mistake: I am not namby-pamby. I am difficult to work for. I demand performance."

A good manager Cafiero defines as one who is "adaptable and dynamic, sensitized to what's going on, who develops an environment where people feel comfortable, where creative things can happen." In executive conferences, management trainee sessions, and plant meetings, Cafiero preaches the need for experimentation. "We want to give our people an opportunity to try new things without worrying about getting their heads chopped off if it doesn't work out," he says, conceding that "they don't always believe me."

The greatest resistance to his approach, revolutionary by Detroit standards, comes from middle management, that group between the top executive who sees a problem in broad perspective and the foreman who is directly up against it. Conditioned by a tradition which has put little premium on risk-taking, they are most skeptical of change.

Cafiero expresses boundless faith in "the fantastic potential of people" and a firm conviction that "we can solve anything if we can tap that talent." He is optimistic about Chrysler s future in a highly competitive, unpredictable market if management remains responsive, flexible, willing to abandon old ways and to enlist the best educated work force in history in the effort.

Trying harder is what's good for Chrysler.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureJUST LIKE THE REST OF US

November 1976 By A. KELLEY FEAD -

Feature

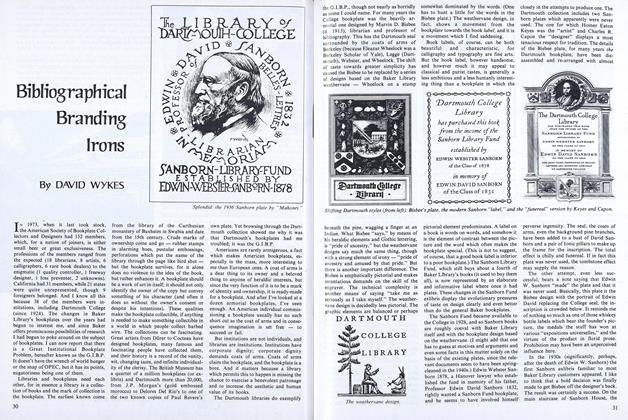

FeatureBibliographical Branding Irons

November 1976 By DAVID WYKES -

Feature

FeatureThe and the

November 1976 By JAMES L. FARLEY -

Feature

FeatureFive Deadly Threats

November 1976 By John G. Kemeny -

Article

ArticleEight-y!

November 1976 -

Article

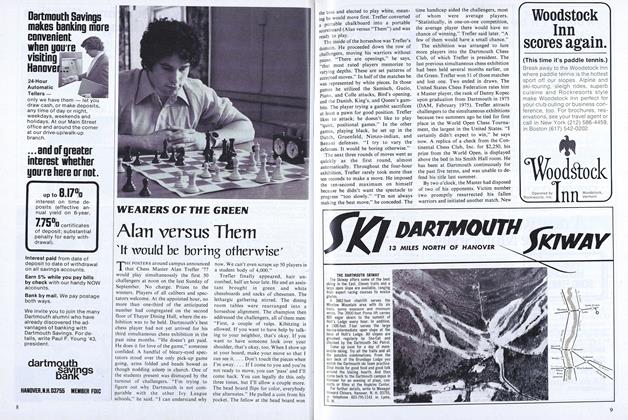

ArticleAlan versus Them 'It would be boring otherwise'

November 1976 By PIERRE KIRCH'78

M.B.R.

Article

-

Article

ArticleSONG PRIZE UNCLAIMED

November, 1912 -

Article

ArticleTRUSTEE MEETING

JULY 1931 -

Article

ArticleOpening soon: the Hood

June • 1985 -

Article

ArticleNEW BRITAIN HIGH, COACHED

February 1937 By Crarles W. Smedley '14 -

Article

ArticleAlarm in Alumni Gym

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1985 By Fred Pfaff '85 -

Article

ArticleJuly Issue

June 1940 By The Editor