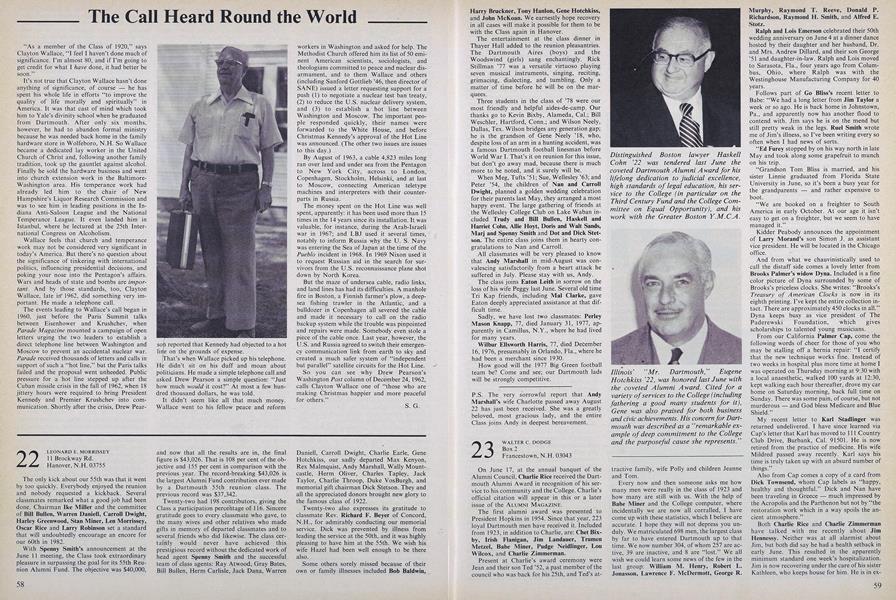

"As a member of the Class of 1920," says Clayton Wallace, "I feel I haven't done much of significance. I'm almost 80, and if I'm going to get credit for what I have done, it had better be soon."

It's not true that Clayton Wallace hasn't done anything of significance, of course - he has spent his whole life in efforts "to improve the quality of life morally and spiritually" in America. It was that cast of mind which took him to Yale's divinity school when he graduated from Dartmouth. After only six months, however, he had to abandon formal ministry because he was needed back home in the family hardware store in Wolfeboro, N.H. So Wallace became a dedicated lay worker in the United Church of Christ and, following another family tradition, took up the gauntlet against alcohol. Finally he sold the hardware business and went into church extension work in the BaltimoreWashington area. His temperance work had already led him to the chair of New Hampshire's Liquor Research Commission and was to see him in leading positions in the Indiana Anti-Saloon League and the National Temperance League. It even landed him in Istanbul, where he lectured at the 25th International Congress on Alcoholism.

Wallace feels that church and temperance work may not be considered very significant in today's America. But there's no question about the significance of tinkering with international politics, influencing presidential decisions, and poking your nose into the Pentagon's affairs. Wars and heads of state and bombs are important. And by those standards, too, Clayton Wallace, late in 1962, did something very important. He made a telephone call.

The events leading to Wallace's call began in 1960, just before the Paris Summit talks between Eisenhower and Krushchev, when Parade Magazine mounted a campaign of open letters urging the two leaders to establish a direct telephone line between Washington and Moscow to prevent an accidental nuclear war. Parade received thousands of letters and calls in support of such a "hot line," but the Paris talks failed and the proposal went unheeded. Public pressure for a hot line stepped up after the Cuban missile crisis in the fall of 1962, when 18 jittery hours were required to bring President Kennedy and Premier Krushchev into communication. Shortly after the crisis, Drew Pearsoft reported that Kennedy had objected to a hot line on the grounds of expense.

That's when Wallace picked up his telephone. He didn't sit on his duff and moan about politicians. He made a simple telephone call and asked Drew Pearson a simple question: "Just how much would it cost?" At most a few hundred thousand dollars, he was told.

It didn't seem like all that much money. Wallace went to his fellow peace and reform workers in Washington and asked for help. The Methodist Church offered him its list of 50 eminent American scientists, sociologists, and theologians committed to peace and nuclear disarmament, and to them Wallace and others (including Sanford Gottlieb '46, then director of SANE) issued a letter requesting support for a push (1) to negotiate a nuclear test ban treaty, (2) to reduce the U.S. nuclear delivery system, and (3) to establish a hot line between Washington and Moscow. The important people responded quickly, their names were forwarded to the White House, and before Christmas Kennedy's approval of the Hot Line was announced. (The other two issues are issues to this day.)

By August of 1963, a cable 4,823 miles long ran over land and under sea from the Pentagon to New York City, across to London, Copenhagen, Stockholm, Helsinki, and at last to Moscow, connecting American teletype machines and interpreters with their counterparts in Russia.

The money spent on the Hot Line was well spent, apparently: it has been used more than 15 times in the 14 years since its installation. It was valuable, for instance, during the Arab-Israeli war in 1967; and LBJ used it several times, notably to inform Russia why the U. S. Navy was entering the Sea of Japan at the time of the Pueblo incident in 1968. In 1969 Nixon used it to request Russian aid in the search for survivors from the U.S. reconnaissance plane shot down by North Korea.

But the maze of undersea cable, radio links, and land lines has had its difficulties. A manhole fire in Boston, a Finnish farmer's plow, a deepsea fishing trawler in the Atlantic, and a bulldozer in Copenhagen all severed the cable and made it necessary to call on the radio backup system while the trouble was pinpointed and repairs were made. Somebody even stole a piece of the cable once. Last year, however, the U.S. and Russia agreed to switch their emergency communication link from earth to sky and created a much safer system of "independent but parallel" satellite circuits for the Hot Line.

So you can see why Drew Pearson's Washington Post column of December 24, 1962, calls Clayton Wallace one of "those who are making Christmas happier and more peaceful for others."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureMen and Women: What's the Difference?

October | November 1977 By Dan Nelson, Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureThe Singing of the Cider

October | November 1977 By Sanborn Brown -

Feature

FeatureThe Bakke Case

October | November 1977 By John G. Kemeny -

Feature

FeatureWith Pen In Hand...

October | November 1977 By Arnold Roth -

Class Notes

Class Notes1971

October | November 1977 By THOMAS G. JACKSON -

Article

Article"My hardships were excessive"

October | November 1977

S.G.

-

Article

ArticleA Versatile, Admirable Teacher With "Every Feature of a Drill Sergeant'(sic)

March 1977 By S.G. -

Article

ArticleA Red Letter Day

April 1977 By S.G. -

Article

ArticleDick's House Is Her House

NOV. 1977 By S.G. -

Article

ArticleResident Rotiferologist

DEC. 1977 By S.G. -

Article

ArticleAlchemist to the College

APRIL 1978 By S.G. -

Feature

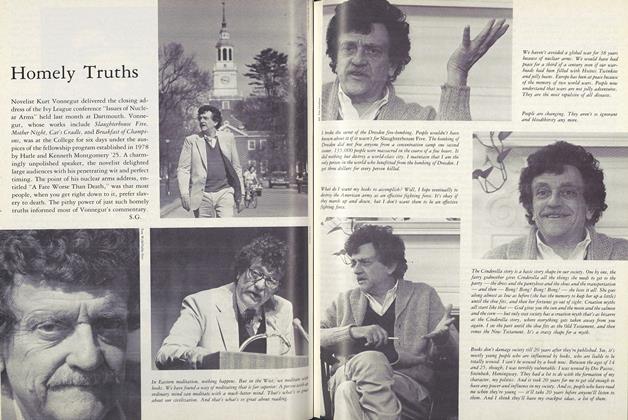

FeatureHomely Truths

JUNE 1983 By S.G.