Harold Ingersoll '17 recalls vividly the sinking of the Titanic and Prohibition. He remembers the war to end all wars and the one that followed it, too. He saw the century turn and the automobile arrive. And he went through the Depression: "It was a time that I will never forget. There was no money and there were no jobs. Even food was hard to get. After the Depression I swore that I would never be without a job."

He meant it. Ingersoll is 84 now, and he still works a five-day week doing cartographic research and drafting at the American Automobile Association's national head-quarters in Falls Church, Va. Ingersoll, who took a Thayer School degree in civil engineering as well as a B.S. from the College, has held in his long working life a number of positions, most of them connected with engineering and mapping. He began in 1917 as a topographer with the U.S. Geological Survey and then went overseas with the Army. After the war he did stints as a draftsman, an accountant, and a construction company straw boss. He helped engineer projects ranging from bridges to Atlantic City amusement devices. Later there were soil conservation and flood control work and also a season of family business, building bridges, jetties, and houses with his father and brother. The Second World War saw him back in the Army as chief terrain analysis adviser to Omar Bradley. After that war, he settled into a position in intelligence work at the CIA. It was from there that he went to AAA.

"I had reached the age of government retirement," he explains, "but I didn't want to retire. However, I knew that the time had come and that I had to leave-the CIA or they would force me to retire. So I applied for instructorships in engineering schools, and I advertised in the 'work wanted' columns, and I combed the want ads. All of this led to an offer from AAA. I announced my retirement on a Friday, took the weekend to rest, and started work at AAA, part-time, on Monday."

Ingersoll rises at 4:30 seven days a week. After a light breakfast, he "reads, thinks, plans, relaxes, and rests" until 6:30. He is at'work by 8:00, and after lunch, around 1:30 or so, he quits for the day. He dines at 6:00, often in a community cafeteria with some of the good company in his apartment building (he is a widower), and is in bed by 7:30.

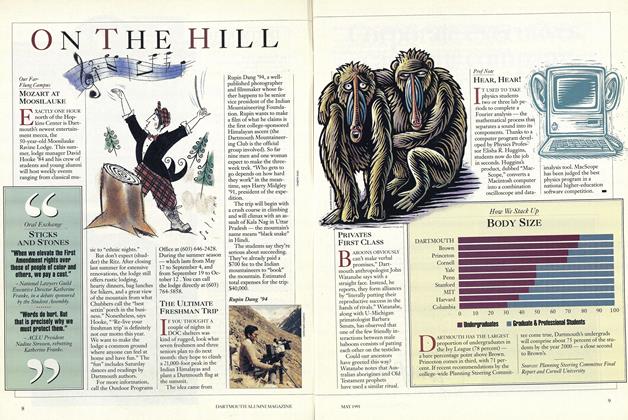

He finds the work at AAA "very satisfying." It has involved a multitude of duties, such as designing a photo lab, laying out new maps, preparing slides for training programs, and exploiting satellite imagery for the mountain plates used to print the relief portions of AAA's road maps. It is this last which Ingersoll regards as his most significant work at the association. Fascinated by the photographic images produced by satellites, Ingersoll has a great respect for the technology which can with such accuracy and clarity depict the surface of the earth.

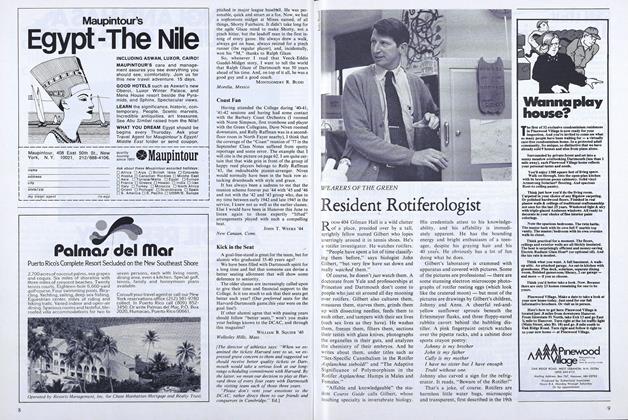

His work is done with images produced by LANDSAT satellites, which orbit some 570 miles above the earth's surface. The satellites' electronic signals are converted to photographic images and made available to the public through the EROS (Earth Resources Observations Systems) Data Center in South Dakota. AAA purchases from EROS small (2" x 2") negatives, or "chips," used to make topographical mosaics. Ingersoll works with a positive print enlargement of the chip, preparing for it a transparent overlay which pinpoints landmarks AAA maps will show - cities, waterways, lakes, and mountains (which are especially well-defined by satellite photography). His hand is still remarkably steady: the fine-line italic lettering he uses on the overlays is very little less certain than it was in 1920 when he used it to fill out a "War Record" form for the College.

Cartographers have only recently begun to use satellite imagery instead of artist's renderings for mountain plates, and the idea is still a bit controversial at AAA, says Ingersoll. There are several disadvantages to using LANDSAT data, among them expense (it takes about 230 chips to cover the 48 states, at $8 a chip) and the uneven density of adjacent chips. Also, some feel that the shading of mountains on maps is more effectively rendered by an artist's airbrush. But for Ingersoll, who gets a "lift" from the satellite photography, there is no doubt. "God's handiwork appeals to me," he says.

Ingersoll, who intends to,keep his job "as long as health and competence permit," has a tolerant philosophy of work and retirement: "Doing what you like to do is appealing. We all differ in our likes and dislikes. I like a person who quits work young and enjoys many happy years of whatever. Such a person is like me, doing what he or she likes. Let's let this freedom of choice continue, without more regulation." If he is let go from AAA, declares Ingersoll, he will continue working at some activity on a contract or piece-work basis. "Beyond that,' he says with the candor of wisdom and courage, "night will be closing in."

God's handiwork: LANDS AT photographof northern Italy was taken from 570 milesup. Harold Ingersoll's overlay marks darkspot low in center as Milan; above it, forkedLake Como nestles among the snowy Alps,

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureScions of Rhodes

January | February 1978 By Daniela Weiser-Varon -

Feature

FeatureOf Sun-Gazers and Seal-Hunters

January | February 1978 By James L. Farley -

Feature

FeatureWINTER

January | February 1978 By Woody Rothe -

Feature

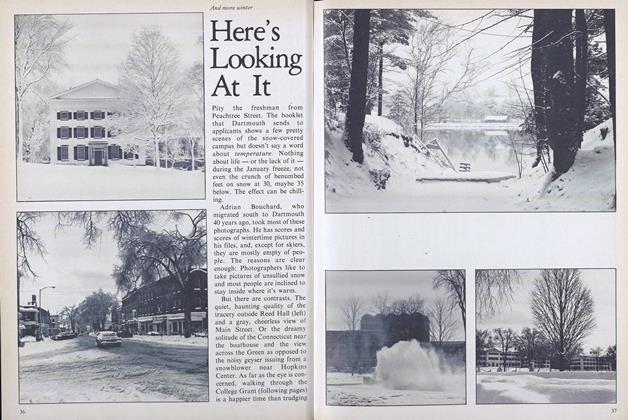

FeatureHere's Looking At It

January | February 1978 -

Article

ArticleGuardian of the Oasis

January | February 1978 By M.H. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

January | February 1978 By WALTER C. DODGE

S.G.

-

Article

ArticleA Versatile, Admirable Teacher With "Every Feature of a Drill Sergeant'(sic)

March 1977 By S.G. -

Article

ArticleA Red Letter Day

April 1977 By S.G. -

Article

ArticleThe Call Heard Round the World

OCT. 1977 By S.G. -

Article

ArticleResident Rotiferologist

DEC. 1977 By S.G. -

Article

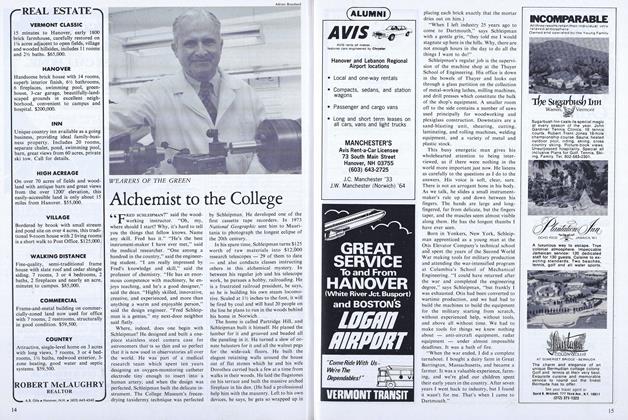

ArticleAlchemist to the College

APRIL 1978 By S.G. -

Feature

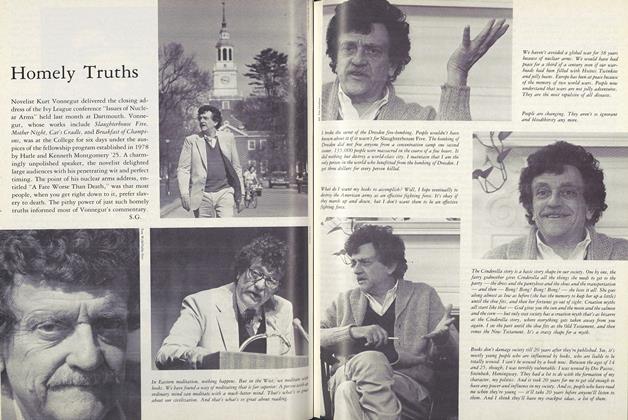

FeatureHomely Truths

JUNE 1983 By S.G.